The AP U.S. History exam consists of multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and free-response questions (FRQs). This guide focuses on the FRQ section. We'll examine the format, provide strategies for scoring well, and offer examples of past FRQ prompts. By the end, you'll be prepared for the essay portion of the APUSH exam.

AP United States History free-response questions (FRQs) are important parts of the exam. They assess students' critical thinking and analytical writing skills in relation to historical events and themes. Students must construct well-organized essays, using evidence to demonstrate a deep understanding of U.S. history.

Format of AP U.S. History FRQ section

A frequently asked question is, "How many FRQs are on the AP U.S. History exam?" The AP U.S. History exam has 2 FRQs: one document-based question (DBQ) and one long essay question (LEQ). You have 1 hour and 40 minutes to answer the 2 questions: 60 minutes for the DBQ and 40 minutes for the LEQ, although you can use more or less time on each.

Each essay is scored on a scale from 0 to 6.

| APUSH FRQ Section Weights and Time Allotments1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sections | Parts | Question Types | Time Allocated | Weight |

| Section II | Part A | 1 DBQ | 60 minutes | 25% |

| Part B | 1 LEQ | 40 minutes | 15% | |

How to Answer AP U.S. History Free-Response Questions

Here are some general tips for approaching the APUSH free-response questions:

Before you begin, review each prompt and start with the one that seems simplest.

Starting with the easiest AP U.S. History FRQ can boost your confidence. Some students find the LEQ easiest since it doesn't require reading documents, while others prefer the DBQ because the provided documents help answer unfamiliar topics. Many save the DBQ for last to quickly write the simpler essay first, allowing more time for the harder one.

State your thesis in the introduction.

Your thesis should present a defensible interpretation, not a summary or restatement of the prompt. A defensible interpretation should be the main idea from the passage or poem that is relevant to the prompt. Don’t spend too much time on the introduction – 2 or 3 sentences are enough. If time is running out, write at least a thesis statement for each essay to earn some points.

Use evidence from the text to support your interpretation.

To score well on the APUSH FRQs, use paraphrased evidence to support the ideas in your essay. Focus on specific words and details that strengthen your argument. Explain how the evidence supports your claim. Two pieces of evidence for each point are enough. Avoid including a list of quotes without explaining how they support your interpretation.

You do not need a conclusion to earn a high score.

You should include one only if you have time to write a concluding sentence that ties your ideas together and makes your essay sound complete.

Don’t worry about making spelling, punctuation, and grammar mistakes.

AP graders understand that you are under time constraints, and your essay may resemble a rough draft. If you make a mistake or change your mind, cross it out and continue.

AP U.S. History FRQ Examples

Here are some examples of APUSH FRQs from previous exams. These questions are taken directly from the College Board®’s Course Description Guide and can serve as practice resources.

The writing component is divided into 2 parts:

Document-Based Question (Free-Response Question 3 on the AP Exam)

A document-based question (DBQ) requires writing an argument using information from 6 out of 7 provided documents and your historical knowledge. This challenging essay accounts for 25% of the AP exam score, with 15 minutes for reading and 45 minutes for writing. The documents include primary texts, secondary texts, and images related to the prompt's time period.

Begin with an introduction, establish your thesis, and outline your argument. Use at least 3 documents to receive credit and 6 for full credit. Describe the historical context and add outside knowledge in the first body paragraph. Use the second and third paragraphs to support your thesis with documents. Paraphrasing instead of quoting shows deeper understanding. Conclude by summarizing your thesis and main arguments. Practice and time management are crucial for success.

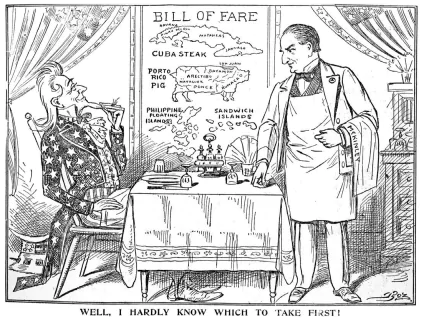

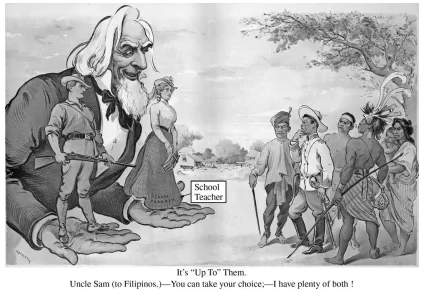

DOCUMENT-BASED QUESTION

Evaluate the relative importance of different causes for the expanding role of the United States in the world from 1865 to 1910.

In your response, you should do the following:

- Respond to the prompt with a historically defensible thesis or claim establishing a line of reasoning.

- Describe a broader historical context relevant to the prompt.

- Support an argument in response to the prompt using at least six documents.

- Use at least one additional piece of specific historical evidence (beyond that found in the documents) relevant to an argument about the prompt.

- For at least three documents, explain how or why the document’s point of view, purpose, historical situation, and/or audience are relevant to an argument.

- Use evidence to corroborate, qualify, or modify an argument that addresses the prompt.

Document 1

Source: Treaty concerning the Cession of the Russian Possessions in North America by his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias to the United States of America, June 20, 1867.

His Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias agrees to cede to the United States, by this convention, immediately upon the exchange of the ratifications thereof, all the territory and dominion now possessed by his said Majesty on the continent of America and in the adjacent islands, the same being contained within the geographical limits herein set forth. . . .

The inhabitants of the ceded territory, according to their choice . . . may return to Russia within three years; but if they should prefer to remain in the ceded territory, they, with the exception of uncivilized native tribes, shall be admitted to the enjoyment of all the rights, advantages, and immunities of citizens of the United States, and shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty, property, and religion. The uncivilized tribes will be subject to such laws and regulations as the United States may, from time to time, adopt in regard to aboriginal tribes of that country. . . .

In consideration of the cession aforesaid, the United States agreed to pay seven million two hundred thousand dollars in gold.

Document 2

Source: Josiah Strong, Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Present Crisis, 1885.

It seems to me that God, with infinite wisdom and skill, is training the Anglo-Saxon race for an hour sure to come in the world’s future. Heretofore there has always been in the history of the world a comparatively unoccupied land westward, into which the crowded countries of the East have poured their surplus populations. But the widening waves of migration, which millenniums ago rolled east and west from the valley of the Euphrates, meet today on our Pacific coast. There are no more new worlds. The unoccupied arable lands of the earth are limited, and will soon be taken. The time is coming when the pressure of population on the means of subsistence will be felt here as it is now felt in Europe and Asia. Then will the world enter upon a new stage of its history—the final competition of races, for which the Anglo-Saxon is being schooled. . . . Then this race of unequaled energy, with all the majesty of numbers and the might of wealth behind it—the representative, let us hope, of the largest liberty, the purest Christianity, the highest civilization—having developed peculiarly aggressive traits calculated to impress its institutions upon mankind, will spread itself over the earth.

Document 3

Source: Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, 1897.

To affirm the importance of distant markets, and the relation to them of our own immense powers of production, implies logically the recognition of the link that joins the products and the markets,—that is, the carrying trade; the three together constituting that chain of maritime power to which Great Britain owes her wealth and greatness. Further, is it too much to say that, as two of these links, the shipping and the markets, are exterior to our own borders, the acknowledgment of them carries with it a view of the relations of the United States to the world radically distinct from the simple idea of selfsufficingness?. . . There will dawn the realization of America’s unique position, facing the older worlds of the East and West, her shores washed by the oceans which touch the one or the other, but which are common to her alone.

Despite a certain great original superiority conferred by our geographical nearness and immense resources,—due, in other words, to our natural advantages, and not to our intelligent preparations,—the United States is woefully unready, not only in fact but in purpose, to assert in the Caribbean and Central America a weight of influence proportioned to the extent of her interests. We have not the navy, and, what is worse, we are not willing to have the navy, that will weigh seriously in any disputes with those nations whose interests will conflict there with our own. We have not, and we are not anxious to provide, the defence of the seaboard which will leave the navy free for its work at sea. We have not, but many other powers have, positions, either within or on the borders of the Caribbean.

Document 4

Document 5

Source: John Hay, United States Secretary of State, The Second Open Door Note, July 3, 1900.

To the Representatives of the United States at Berlin, London, Paris, Rome, St. Petersburg, and Tokyo Washington, July 3, 1900

In this critical posture of affairs in China it is deemed appropriate to define the attitude of the United States as far as present circumstances permit this to be done. We adhere to the policy . . . of peace with the Chinese nation, of furtherance of lawful commerce, and of protection of lives and property of our citizens by all means guaranteed under extraterritorial treaty rights and by the law of nations. . . . We regard the condition at Pekin[g] as one of virtual anarchy. . . . The purpose of the President is . . . to act concurrently with the other powers; first, in opening up communication with Pekin[g] and rescuing the American officials, missionaries, and other Americans who are in danger; secondly, in affording all possible protection everywhere in China to American life and property; thirdly, in guarding and protecting all legitimate American interests; and fourthly, in aiding to prevent a spread of the disorders to the other provinces of the Empire and a recurrence of such disasters. . . .

The policy of the Government of the United States is to seek a solution which may bring about permanent safety and peace to China, preserve Chinese territorial and administrative entity, protect all rights guaranteed to friendly powers by treaty and international law, and safeguard for the world the principle of equal and impartial trade with all parts of the Chinese Empire.

Document 6

Document 7

Source: President Theodore Roosevelt, Fourth Annual Message to Congress, December 6, 1904.

There are kinds of peace which are highly undesirable, which are in the long run as destructive as any war. Tyrants and oppressors have many times made a wilderness and called it peace. Many times peoples who were slothful or timid or shortsighted, who had been enervated by ease or by luxury, or misled by false teachings, have shrunk in unmanly fashion from doing duty that was stern and that needed self-sacrifice, and have sought to hide from their own minds their shortcomings, their ignoble motives, by calling them love of peace. . . .

It is our duty to remember that a nation has no more right to do injustice to another nation, strong or weak, than an individual has to do injustice to another individual; that the same moral law applies in one case as in the other. But we must also remember that it is as much the duty of the Nation to guard its own rights and its own interests as it is the duty of the individual so to do. . . . It is not true that the United States feels any land hunger or entertains any projects as regards the other nations of the Western Hemisphere save such as are for their welfare. All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly, and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and . . . the exercise of an international police power.

Source: College Board

Long Essay Question (Free-Response Question 4 on the AP Exam)

This section will demonstrate how to write a Continuity and Change Over Time (CCOT) essay for the AP U.S. History Exam. You must develop an argument using 1 historical reasoning skill — causation, comparison, continuity, or change over time. The CCOT essay requires a chronological look at history, distinguishing between historical change and continuity. To earn the complexity point, you should address continuity and change in your essay. Here are the steps needed to answer a CCOT prompt effectively.

Long Essay Example Question prompt

Evaluate the extent to which the ratification of the United States Constitution fostered a change in the function of the federal government in the period from 1776 to 1800.

Step one:

This prompt asks students to write about 'change'.

Once the student has analyzed the prompt and decided that using the historical skills of continuity and change over time is best to answer the question, they should take a moment and come up with two or three CHANGES that occurred during the era in the prompt.

Example:

Two regions: Europe and the Americas

Changes:

Rise in indentured servitude

Rise in Irish immigration

For the complexity point, determine one CONTINUITY from the era mentioned in the prompt.

Continuity:

Immigrants continued to flow into the U.S. searching for economic gain

Step two:

Context (one point on both the DBQ and LEQ essays)

From their knowledge of this period in history, what does the student know that could help them analyze (put into context) how long-distance migrations changed during this era?

One way to do this is to situate the argument by explaining the broader historical events, developments, or processes closely relevant to the question. Give historical background for the argument.

- With context, the writer is 'setting the scene' for the essay.

- This requires an explanation, typically consisting of multiple sentences.

- It usually appears in the introduction to your essay at least 2-3 sentences.

Think of contextualization like a TV show. Sometimes, at the beginning of an episode, the producers show scenes from previous episodes to set the stage for the current episode. The show's producers are providing context or background for the current episode.

Step three:

Brainstorming: Think about the chosen "changes" or "continuities".

Analysis: Why did the change occur, and what evidence does the student have to support it? (Being able to demonstrate a 'complex understanding of historical development using evidence to prove the thesis' will earn the student the 'complexity point'.)

- Why was there a rise in indentured servitude?

- Why was there a rise in Irish migration?

Analysis: Why did the continuity occur, and what evidence does the student have to support it? (Being able to demonstrate a 'complex understanding of historical development using evidence to prove the thesis’ will get the student the 'complexity point'.)

- Why did immigrants continue to flow into the U.S. during this era, searching for economic gain?

This will help the student write their thesis statement.

Step four:

Write the thesis.

- The thesis of an essay is the main argument or point. The LEQ and DBQ rubrics for AP U.S. History state that students must provide a "historically defensible thesis that establishes a line of reasoning."

- The student is writing a 'road map' or summary of what the essay will discuss.

- The thesis must consist of one or more sentences located in one place, either in the introduction or the conclusion.

Example:

"From 1700 to 1900, there were many changes in long-distance migrations to Europe and the Americas. Changes included the rise in indentured servitude and Irish migration. One continuity that occurred during this period was the continued flow of immigrants to the U.S. searching for economic wealth."

Step five:

Write the Continuity and Change Over Time Essay AP U.S. History

- Introductory paragraph: Context (setting the scene) and thesis (responding to the prompt with a specific historically defensible claim)

- Questions to consider:

- Does the historical context tie into the prompt?

- Did the student mention continuities/changes in the thesis?

- Questions to consider:

- Body paragraph #1: Changes Rise in indentured servitude

- Historical Reasoning: Topic Statement (Start the paragraph by summarizing the major changes that have taken place. Then add specific and detailed examples throughout the paragraph.)

- Cite supporting evidence: state the WHY something occurred

- Questions to consider:

- What are the changes?

- Did the student give specific examples of the changes and analyze WHY they occurred?

- Did the student provide descriptive evidence to support the topic statement?

- Body paragraph #2: Changes Rise in Irish Migration

- Historical Reasoning: Topic Statement (Start the paragraph by summarizing the major changes that have taken place. Then add specific and detailed examples throughout the paragraph.)

- Cite supporting evidence: give the WHY something occurred

- Questions to consider:

- What are the changes?

- Did the student give specific examples of the changes and analyze WHY they occurred?

- Did the student provide descriptive evidence to support the topic statement?

- Body paragraph #3: Continuities (complexity point

- Historical Reasoning: Topic Statement (Start the paragraph by summarizing the major continuities that have taken place.)

- Provide evidence to support these continuities

- Questions to consider:

- What are the continuities?

- Did the student give specific examples of the continuities and analyze WHY they occurred? (This gets the student the 'complexity point'.)

- Did the student provide descriptive evidence to support the statement?

- Conclusion paragraph: Bring it all together for the reader

- Reaffirm the argument (thesis) by explaining how the examples and descriptive evidence support each topic sentence.

- Questions to consider:

- Did the student's evidence support the thesis?

- Did they answer the prompt fully?

LEQ essay writing checklist

- The essay starts with context or background, which “sets the scene” for the essay.

- The context flows into the thesis statement.

- The introductory paragraph contains the context and thesis.

- The thesis uses the same words as seen in the prompt.

- The thesis answers the prompt and gives specific changes.

- The thesis answers the prompt and gives specific continuities.

- There are at least 5 paragraphs (more is OK).

- The first and second body paragraphs address changes.

- There are specific examples of changes given.

- Analysis is provided, explaining why there have been changes.

- The third body paragraph addresses continuities.

- There are specific examples of continuities given.

- The conclusion paragraph summarizes the essay’s thesis and main points.

- The evidence is specific, and the writing is direct, clear, and ties back to the thesis.

How Can I Practice AP U.S. History Free-Response Questions?

The best way to prepare for AP U.S. History FRQs is by using past questions from College Board exams. If enrolled in an AP class, your instructor will guide you and provide feedback. Familiarize yourself with the scoring rubrics to understand the required information. Practice, gradually reducing the time spent until you can complete a quality essay in 40 minutes. Join UWorld’s APUSH course for a complete study guide and extensive QBank designed to help you ace the exam.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many FRQs are on the AP U.S. History Exam?

How are AP U.S. History FRQs graded?

How long is the FRQ section of the AP U.S. History Exam?

Where can I find FRQs from past AP U.S. History exams?

References

- (2024). Section II: Document-Based Question and Long Essay. Exam Format. AP United States History. Retrieved on December 19, 2024 from https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-united-states-history/exam

Read More About AP U.S. History

Answering MCQs might seem straightforward, but the difference between options can be subtle. Discover how to pinpoint the correct choice for AP U.S. History questions!

How to Write AP U.S. History Modern SAQsNeed strategies for answering AP U.S. History SAQs? We’re here to help — providing tips to succinctly answer each short-answer question to help you ace this section.

AP U.S. History Scoring GuideInterested in learning the APUSH grading system? Visit our article on AP US History scoring and score distribution, which provides a score calculator to help you estimate your scores.

How to Self-study for AP U.S. HistorySelf-studying for AP U.S. History? Use this proven step-by-step guide to master concepts, stay organized, and achieve top exam scores.

Best AP U.S. History Study Guide ComparisonDiscover expert insights into Kaplan, Barron's, Princeton Review, and UWorld. Learn how each resource compares to help you choose the best fit.

Best AP U.S. History Prep Course ReviewDiscover the best AP U.S. History prep courses! This in-depth review helps you compare options and pick the course that meets your needs.