What Is SAT Scoring and Why It Matters

SAT test scores are an important part of college admissions, scholarship eligibility, academic placement, and your overall academic profile. Colleges look at your score range, percentile rank, and section scores to understand your readiness for college-level work. A clear understanding of the SAT scoring scale helps you determine your target score based on your dream schools. Knowing what counts as a great SAT score or a competitive score also helps you build a personalized study plan. If you want to build confidence with a structured learning path, check out our SAT Online Prep Course for in-depth lessons and strategies tailored to your needs.

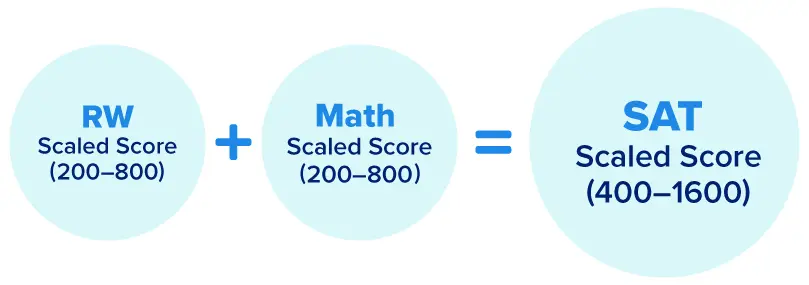

SAT Scoring Scale and Conversion Process

Your SAT test scores are calculated through a structured system that ensures fairness across all test dates. Both sections of the SAT use adaptive modules that adjust question difficulty based on your performance. Your final SAT scores reflect both accuracy and consistency.

SAT Raw Score Conversion

A raw score represents the number of questions you answer correctly in each section. Since there are no penalties for incorrect answers, guessing does not lower your test score. Raw scores show your accuracy and determine which questions appear in the second adaptive module, especially in Math and Reading and Writing. You can improve your raw score accuracy by using realistic SAT practice questions and timed practice tests.

| SAT Scoring | ||

|---|---|---|

| Section | No. of Questions | Raw Score Range |

| Reading and Writing | 54 | 0-54 |

| Math | 44 | 0-44 |

What Are Scaled SAT Scores?

Scaled SAT scores range from 200 to 800 for each section. After calculating your raw scores, the SAT uses the conversion scale to assign a score within this SAT test score range. Scaled scores help colleges compare performance across different test dates. For example, a raw score of 42 out of 44 in Math might translate to a 780 or higher, depending on the scoring scale for that test. This standardization helps maintain fairness and accuracy in SAT scoring.

The Role of Equating in Fair Scoring

Equating is a statistical process used to ensure that SAT scores remain consistent even when tests vary slightly in difficulty. If one version of the test is harder than another, equating adjusts the scaled scores to reflect that difference. This process ensures your SAT score scale remains fair, accurate, and comparable, regardless of when or where you take the test.

SAT Score Range, Chart, and Percentiles

The SAT score range helps you understand where your performance stands compared to other students and what score you should aim for based on your college goals. Each SAT section is scored on a scale from 200 to 800, and these two scores combine to form your total score on a scale of 400 to 1600. Knowing how this range works makes it easier to understand what counts as an average score, a competitive score, or a top score on the SAT. It also helps you track score growth during your practice tests and identify the level you need for your ideal colleges.

Understanding the SAT Score Range

SAT scores fall within a fixed range that helps schools evaluate your academic readiness.

- Total scores range from 400 to 1600

- Section scores range from 200 to 800

- The highest SAT score possible is 1600

- A perfect SAT score is 1600

- The maximum score is 1600

Students aiming for competitive universities often target SAT scores of 1400 or above, while many colleges accept scores between 1100 and 1200. Understanding the SAT test score range helps you set realistic goals aligned with your college list.

Sample SAT Scoring Chart (Raw to Scaled Score)

Sample based on official digital SAT scoring ranges.

| Math (Example) | |

|---|---|

| Raw Score | Scaled Score (Approximate) |

| 44 | 790-800 |

| 42 | 770-790 |

| 40 | 740-760 |

| 35 | 700-720 |

| Reading & Writing (Example) | |

|---|---|

| Raw Score | Scaled Score (Approximate) |

| 54 | 800 |

| 50 | 740-760 |

| 45 | 680-700 |

| 40 | 620-650 |

What Are SAT Score Percentiles and How They Impact College Admissions

SAT score percentiles compare your performance with other test takers and show the percentage of students you outperformed. A score in the 90th percentile means you performed better than 90 percent of students nationwide. Colleges use percentiles to understand how competitive you are in the applicant pool and to evaluate your readiness for college-level work. Strong percentile rankings can also improve your chances of receiving merit aid and scholarships. To explore how percentiles work in more detail, read our guide on SAT percentile.

What Is a Good SAT Score for Different Pathways

A good SAT score depends on your college list, intended major, and the competitiveness of the colleges on your list. Highly selective universities often expect SAT scores in the 1400 to 1500 range, while many colleges consider scores around 1100 to 1200 to be strong. A good SAT score is ultimately one that meets the requirements of your preferred schools and strengthens your chances of admission. You can explore score expectations for different pathways in our full guide on “What is a good SAT score”.

What Is the Average SAT Score

The national average SAT score typically falls between 1050 and 1120 each year. This benchmark helps you see how your performance compares with other test takers and understand whether you may need further preparation. Scoring above the national average increases your chances of admission at many schools, while scoring significantly higher than average may qualify you for competitive scholarships.

SAT Superscore

An SAT superscore combines your highest section scores from multiple SAT attempts to create your strongest possible score. Colleges that accept superscoring will evaluate your best Reading and Writing score and your best Math score, even if they come from different test dates. Superscoring is especially helpful for students who improve one section at a time and want to maximize their composite score for competitive programs. You can learn more about how superscoring works in our guide on SAT superscore.

How Is Each SAT Section Scored

Each SAT section is scored on a scale of 200 to 800, but the scoring process differs slightly based on the adaptive modules and question types. Knowing how each section is scored helps you plan a stronger study strategy.

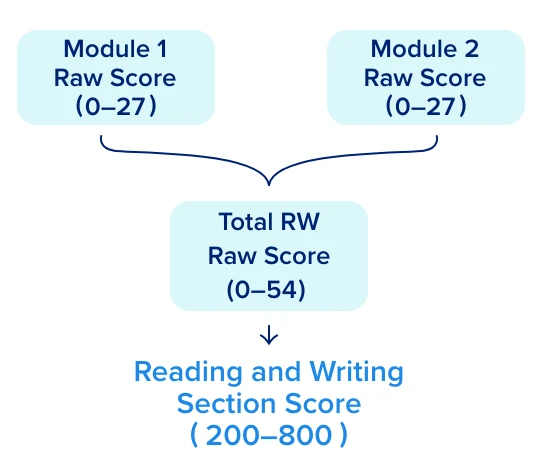

Reading and Writing Section Scoring Structure

Your Reading and Writing score is calculated by adding the correct answers from both adaptive modules. These raw scores are then converted into a scaled score between 200 and 800. This section measures reading comprehension, vocabulary skills, grammar, and editing abilities. Understanding this structure helps you prepare more effectively for high scoring performance.

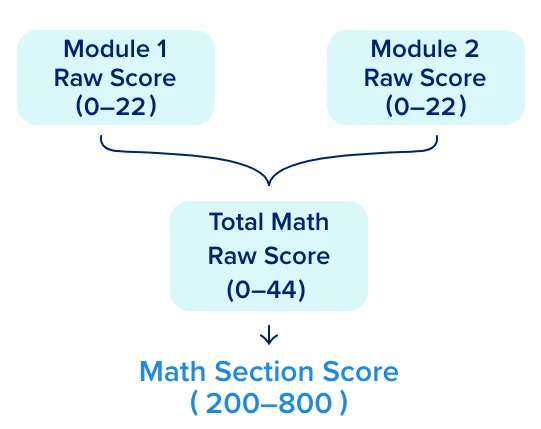

Math Section Scoring Structure

The Math section also uses two adaptive modules. Your total number of correct answers determines your raw score, which is then converted to a scaled score between 200 and 800. Math questions focus on algebra, advanced math, problem solving, geometry, and data analysis. Knowing how raw scores convert into scaled scores helps you understand how many questions you need to get right to reach a high score in SAT Math.

Helpful SAT Score Information for Students

Understanding the details behind your SAT exam scores can help you identify strengths, pinpoint weak areas, and plan your next steps more effectively.

Understanding Your Score Report

Your SAT score report includes detailed information such as section scores, percentiles, benchmarks, and subscores. These insights help you understand your strengths and weaknesses so you can align your study plan with your goals. Reviewing your SAT score report also shows how competitive your score is for the colleges on your list. For a complete breakdown of every part of the report, read our guide on how to interpret the SAT score report. For extra guided practice to strengthen weak areas, take a look at our SAT Study Guide (SAT Prep Book).

Sending Scores to Colleges

You can send SAT scores to colleges directly through your College Board account or choose score recipients before test day. Many colleges accept free score sends within a specific window, while additional reports may require a fee. Understanding how to send SAT scores early helps you stay organized and meet application deadlines without last-minute stress. For step-by-step instructions, read our guide on how to send SAT scores to colleges.

SAT Score Comparison With ACT

Comparing SAT and ACT scores helps you understand which exam showcases your strengths more effectively. ACT to SAT score conversion charts make it easier to compare results because both exams use different scoring scales. Many students use this comparison to decide whether to submit both scores or choose the stronger one for college applications.

SAT Practice Test Scores Explained

Understanding how SAT practice test scores work helps you track your progress and predict your performance on the actual digital SAT.

Do SAT Practice Tests Give You a Score

Yes, digital SAT practice tests give you estimated scaled scores based on your raw performance. UWorld’s SAT practice test scores show you where you stand, highlight your weak areas, and help estimate how you might perform on test day. Taking practice tests consistently to track your score range also helps you set realistic improvement goals as you prepare for the actual exam.

How to Boost Your SAT Practice Score

Improving your SAT practice test scores requires consistent practice, detailed review, and exposure to high quality exam-style questions. Using UWorld’s SAT practice questions helps because the platform offers exam-level difficulty, step-by-step explanations, and adaptive practice that closely mirrors the digital SAT. This level of realism strengthens your accuracy, pacing, and confidence over time. Regular practice combined with in depth answer reviews supports meaningful score improvement. For additional strategies to raise your scores, read our guide on how to improve your SAT score.

SAT Scores: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How does superscoring work?

How long are SAT scores valid?

What is a bad SAT score?

How do I cancel my SAT scores?

How do I verify my SAT scores?

What SAT score is required for a full scholarship?

Is it better to have a good GPA or a high SAT score?

What is a perfect SAT score?

References

- The Digital SAT Suite of Assessments: Test Specifications Overview. (2022). College Board. Retrieved from https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/digital-sat-test-spec-overview.pdf

- Understanding Digital SAT Scores. (Fall 2025). College Board. Retrieved from https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/digital-sat-understanding-scores.pdf

- Your SAT Score Report Explained. College Board. Retrieved from https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/sat/scores/understanding-scores/your-score-report-explained

- SAT Student Guide. (Fall 2025). College Board. Retrieved from https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/sat-student-guide.pdf

- Digital SAT Sample Questions and Explanations. College Board. Retrieved from https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/digital-sat-sample-questions.pdf

- Scoring the Digital SAT Practice Test 4. College Board. Retrieved from https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/scoring-sat-practice-test-4-digital.pdf

Related Articles

Considering taking the SAT? This guide covers everything you need to know, including benefits, difficulty, key topics, dates, and more to help you prepare effectively.

SAT Format & SyllabusUnderstand the SAT format and syllabus in one guide, covering test structure, timing, question types, and major topics, along with useful tips for effective preparation.

How to Study for the SATStruggling with your SAT test prep? Discover the most effective test-taking strategies, a comprehensive study plan, and expert tips to help you boost your SAT score.