The AP World History: Modern exam consists of 2 major sections: multiple-choice questions (MCQs) and free-response questions (FRQs). This guide will focus on everything you need to know about the AP World History FRQ section, including the format, and provide tips to help you score well.

Format of AP World History FRQ Section

Section 2 of the AP World History exam contains 2 types of free-response questions: one document-based question (DBQ) and one long essay question (LEQ). Every essay is graded on a scale of 0 to 6.

| Section II | Time Allocated | Weighting |

|---|---|---|

| Document-Based Question | 60 minutes | 25% |

| Long Essay Question | 40 minutes | 15% |

How to Answer AP World History Free-Response Questions?

Here are some general tips for approaching the AP World History FRQ section:

-

Before you start, review all the prompts and begin with the easiest one.

Starting with the easiest question can boost your confidence for the rest of the exam. For some students, the LEQ may be easiest since it does not require you to read documents to answer the question. For other students, the DBQ is easier because, even if you are unfamiliar with the topic of the question, the documents can aid in answering. Many students choose to answer the DBQ last because they prefer to quickly write the easier essays so they have more time for the harder ones.

-

State your thesis in the introduction.

Your thesis must contain a defensible interpretation, not a summary or restatement of the prompt. A defensible interpretation is the main idea you got from the passage or poem that applies to the prompt's focus. Don’t spend too much time on your introduction. Two or 3 sentences are sufficient. If you are running out of time, write at least a thesis for all your essays because you will receive at least a point. (Note: SAQs won't require a thesis statement)

-

Use evidence from the text to support your interpretation.

To score well on the AP World History free-response questions, include paraphrased proof of your ideas in your essay. Focus on specific words and details that support what you have to say. Be sure to explain how the evidence illustrates your idea. Two pieces of evidence for each of your points are sufficient. Don’t include lists of quotes without explaining how they support your interpretation.

-

You do not need a conclusion to earn a high score.

You should write a conclusion if you have time to write a sentence that pulls your ideas together. But they are not necessary.

-

Don’t worry about making spelling, punctuation, and grammatical mistakes.

The graders understand that you are writing under time constraints and your essay is more like a rough draft. So, your spelling and grammar errors are not taken much seriously.

AP World History FRQ Examples

Here are some examples of free-response questions from previous AP World History exams. These questions are taken directly from the College Board® Course Description guide. The writing component is divided into 2 parts:

Document-Based Question

A DBQ is an essay question that provides you with 7 documents and asks you to write an argument based on a prompt and using information from 6 of the documents. In this type of essay, you will be asked to make connections between 2 or more documents in addition to calling upon your outside historical knowledge.

The DBQ is worth 25% of the AP exam, and you are given 60 minutes to complete it. The expectation is to spend 15 minutes reading the documents and the remaining 45 minutes writing.

The documents will include primary texts, secondary texts, and images and will be related to the time period of your prompt. Read through the documents thoroughly, spending no more than 15 minutes on them. The point of this essay is to provide a thesis and prove that point with evidence from the documents. You must use at least 3 documents to get credit. For full credit, you'll need to use 6 documents to prove your thesis.

Start your essay by writing an introduction, setting up your thesis, and dividing your argument into several steps. In the first paragraph, tell the reader the historical situation and include previous historical knowledge you have that is outside the documents. In the second and third paragraphs, restate the point made in the thesis and use documents to explain and prove your point. Try to use 2 or 3 documents. If you made more than 2 points, write a fourth paragraph and use 1 or 2 additional documents as evidence. In your conclusion, restate your thesis, summarize the main arguments, and tell the reader how they fit together.

Try to paraphrase over direct quoting, showing the reader a deeper level of understanding. Managing your time is a big part of essay writing, which is why practicing beforehand is helpful.

Document-based Question (DBQ) Example

Evaluate the extent to which the experience of the First World War changed relationships between Europeans and colonized peoples.

In your response you should do the following:

- Respond to the prompt with a historically defensible thesis or claim that establishes a line of reasoning.

- Describe a broader historical context relevant to the prompt.

- Support an argument in response to the prompt using at least six documents.

- Use at least one additional piece of specific historical evidence (beyond that found in the documents) relevant to an argument about the prompt.

- For at least three documents, explain how or why the document's point of view, purpose, historical situation, and/or audience is relevant to an argument.

- Use evidence to corroborate, qualify, or modify an argument that addresses the prompt.

Document 1

Source: John Chilembwe, native of British Nyasaland (present-day Malawi) and ordained Baptist minister, letter sent to the Nyasaland Times,* November 1914.

We have been invited to shed our innocent blood in this world war which is now in progress. In the past, it was said indirectly that Africa had nothing to do with the civilized world. But now we find that the poor African has already been plunged into the great war. The masses of our people are ready to put on uniforms, ignorant of what they have to face or why they have to face it. We natives have been loyal since the commencement of this [British] Government, and in all departments of Nyasaland the welfare of the British would have been incomplete without our loyalty. But in time of peace the Government failed to help the underdog. In time of peace everything was for Europeans only. But in time of war it has been found that we are needed to share hardships and shed our blood in equality. The poor Africans who have nothing to win in this present world are invited to die for a cause which is not theirs.

*The letter was published but later retracted by the newspaper’s British editors, and the entire issue was subsequently withdrawn from circulation and destroyed by the Nyasaland colonial government.

Document 2

Source: Kalyan Mukerji, Indian officer in the British Indian army that was fighting against the Ottoman army in Iraq, letter to a friend in India, October 1915. The letter was intercepted by British mail censors and was not delivered.

England is the educator. The patriotism that the English have taught us, the patriotism that all civilized nations have celebrated—that patriotism is responsible for all this bloodshed. We see now that all that patriotism means is snatching away another man’s country. To show patriotism, nationalism, by killing thousands and thousands of people all to snatch away a bit of land, well it’s the English who have taught us this.

The youths of our country, seeing this, have started to practice this brutal form of nationalism. Therefore, killing a number of people, throwing bombs—they have started doing these horrific things. Shame on patriotism. As long as this narrow-mindedness continues, bloodshed in the name of patriotism will not cease. Whether a man throws a bomb from the roof-top or whether fifty men, under orders from their officer, start firing from a cannon-gun at the front line—the cause of this bloodshed, this madness, is the same.

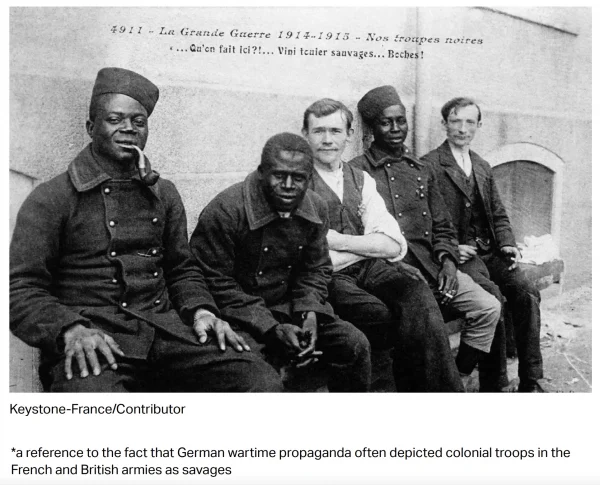

Document 3

Source: French postcard, showing colonial troops in France and French civilians, 1915. The text of the card says: “Our Black troops in the Great War 1914–1915 [say]: ‘What are we doing here?! . . . We came to kill savages*. . .the German ones!’”

Document 4

Source: Behari Lal, Indian soldier in the British Indian army on the Western Front, letter to his family, November 1917. The letter was intercepted by British mail censors and was not delivered.

There is no likelihood of our getting rest during the winter. I am sure German prisoners would not be worse off in any way than we are. I had to go three nights without sleep, as I was on a truck, and the Europeans on the truck did not like to sleep next to me because I am an Indian. I am sorry the hatred between Europeans and Indians is increasing instead of decreasing, and I am sure the fault is not with the Indians. I am sorry to write this, which is not a hundredth part of what is in mind, but this increasing hatred and continued ill-treatment has compelled me to give you a hint.

Document 5

Source: Popular Egyptian protest song sung during the Egyptian revolt of 1919 against the British occupation of Egypt. The revolt led to Great Britain’s recognition of Egypt’s nominal independence in 1922.

Laborers and soldiers were forced to travel, leaving their land. They headed to the battlefields and the trenches!

And now the British blame us for revolting? Behold the calamities you have caused! Had it not been for our laborers, You and your troops would have been helpless in the desert sand!

Oh, you who are in authority, why didn’t you go all alone to the Dardanelles?*

Oh Maxwell** now you feel the hardships, how does it feel?

The Egyptian is resilient; and now he is willing and able and can do anything.

His achievements are worthy of praise, and he will do his all to gain a constitution.

We are the sons of Pharaohs, which no one can dispute. . . .

*The Dardanelles, a narrow strait of water in northwest Turkey, was the site of the famous 1915–1916 Gallipoli campaign. During the campaign, Allied forces attacked the Ottoman Empire and were defeated.**British commander in Egypt in 1915.

Document 6

Source: Hubert Reid, Jamaican veteran of a West Indian regiment in the British Army and leader of a labor union formed to defend the rights of Jamaican war veterans, petition to the British colonial government, 1935.

It has taken 17 years of countless petitions, marching through the streets of Kingston,* as well as agitations before we were given worthless lands in some of the most remote parts of the island without even a well-needed five-pound bill to assist us in making a shabby shelter, much less in trying to cultivate the place for an existence. In some cases, not even wild birds would care to inhabit the worthless lands that we were given. Not even an inch is suitable for cultivation, and as far as roads are concerned, the inaccessibility of the places renders that impossible. *the Jamaican capital

Document 7

Source: Nar Diouf, African veteran of a West African regiment in the French army, interview for an oral history project, 1982.

My experience in the war gave me many lasting things. I demonstrated my dignity and courage, and I won the respect of my people and the [French colonial] government. In the years immediately after the war, whenever the people of my village had something to contest with the French—and they didn’t dare do it themselves because they were afraid—I would go and take care of it for them. And many times when people had problems with the government, I would go with my war decorations and arrange the situation for them. Because whenever the French saw your decorations, they knew that they are dealing with a very important person. So I gained this ability— to obtain justice over the Europeans—from the war. For example, one day a French military doctor was in our village, and there was a small boy who was blind. The boy was walking, but he couldn’t see and he bumped into the Frenchman. And the Frenchman turned and pushed the boy down on the ground. And when I saw this, I came and said to the Frenchman: “Why did you push the boy? Can’t you see that he is blind?” And he looked at me and said: “Oh, pardon, pardon. I did not know. I will never do it again, excuse me!” But before the war, it would not have been possible for me to interact like that with a European, no matter what he had done.

Source: College Board

Long Essay Question

For this section, you will write a continuity and change over time (CCOT) long essay for the AP World History Exam.

You will be asked to use a historical reasoning skill — causation, comparison, or continuity and change over time — to develop an argument in response to the prompt.

The first thing to remember about the historical skill of change and continuity over time for AP World History is that it is a chronological look at history. You need to be able to identify historical "change" as well as historical "continuity" — the things that stay the same. With the CCOT essay, you will be asked to write on either continuity or change, and you can receive the complexity point for writing about both.

Long Essay Example Question prompt:

Develop an argument that evaluates the extent to which long-distance migrations from Europe to the United States changed from 1700 to 1900.

Step One

This prompt asks students to write about 'change'.

Once the student has analyzed the prompt and decided that using the historical skill, continuity and change over time, is best to answer the question, they should take a moment and come up with two or three CHANGES that occurred during the era in the prompt.

Example:

Two regions: Europe and the Americas

-

Changes:

- Rise in indentured servitude

- Rise in Irish immigration

- For the complexity point, determine one CONTINUITY from the era mentioned in the prompt.

-

Continuity:

- Immigrants continued to flow into the US searching for economic gain

Step Two

Context (one point on both the DBQ and LEQ essays)

From their knowledge of this period in history, what do the student know that could help them analyze (put into context) how long-distance migrations changed during this era?

- One way to do this is to situate the argument by explaining the broader historical events, developments, or processes closely relevant to the question. Give historical background for the argument.

- With context the writer is 'setting the scene' for the essay.

- This requires an explanation typically consisting of multiple sentences.

- It usually appears in the introduction to your essay-at least 2-3 sentences.

- Think of contextualization like a TV show. Sometimes at the beginning of an episode, the producers show scenes from previous episodes to set the stage for the current episode. The show's producers are providing context or background for the current episode.

Step Three

Brainstorming: Think about the "changes" or "continuities" that were decided on.

Analysis: Why did the change occur and what evidence does the student have to support it? (Being able to demonstrate a 'complex understanding of historical development using evidence to prove the thesis' will earn the student the 'complexity point')

- Why was there a rise in indentured servitude?

- Why was there a rise in Irish migration?

Analysis: Why did the continuity occur and what evidence does the student have to support it? (Being able to demonstrate a 'complex understanding of historical development using evidence to prove the thesis" will gets the student the 'complexity point')

- Why did immigrants continued to flow into the US during this era searching for economic gain?

This will help the student write their thesis statement.

Step Four

Write the thesis

- The thesis of an essay is the main argument or point. The LEQ and DBQ rubric for AP World History states that students must provide a "historically defensible thesis that establishes a line of reasoning."

- The student is writing a 'road map' or summary of what the essay will discuss.

- The thesis must consist of one or more sentences located in one place, either in the introduction or the conclusion.

Example:

"From 1700 to 1900, there were many changes in long-distance migrations to Europe and the Americas. Changes included the rise in indentured servitude and Irish migration. One continuity that occurred during this period was the continued flow of immigrants to the US searching for economic wealth."

Step Five

Write the essay!!

Introductory paragraph: Context (setting the scene) and thesis (responds to the prompt with a specific historically defensible claim)

- Questions to consider:

- Does the historical context tie into the prompt?

- Did the student mention continuities/changes in the thesis?

Body paragraph #1: Changes Rise in indentured servitude

- Historical Reasoning: Topic Statement (start the paragraph by summarizing the major changes that have taken place. Then add specific and detailed examples throughout the paragraph

- Cite supporting evidence: state the WHY something occurred

- Questions to consider:

- What are the changes?

- Did the student give specific examples of the changes and analyze WHY they occurred?

- Did the student provide descriptive evidence to support the topic statement?

Body paragraph #2: Changes Rise in Irish migration

- Historical Reasoning: Topic Statement (start the paragraph by summarizing the major changes that have taken place. Then add specific and detailed examples throughout the paragraph)

- Cite supporting evidence: give the WHY something occurred

- Questions to consider:

- What are the changes?

- Did the student give specific examples of the changes and analyze WHY they occurred?

- Did the student provide descriptive evidence to support the topic statement?

Body paragraph #3: Continuities (complexity point)

- Historical Reasoning: Topic Statement (start the paragraph by summarizing the major continuities that have taken place)

- Provide evidence to support these continuities

- Questions to consider:

- What are the continuities?

- Did the student give specific examples of the continuities and analyze WHY they occurred? (This gets the student the 'complexity point')

- Did the student provide descriptive evidence to support the statement?

Conclusion paragraph: Bringing it all together for the reader

- Reaffirms the argument (thesis) by explaining how the examples and descriptive evidence supports each topic sentence

- Questions to consider:

- Did the student's evidence support the thesis?

- Did they answer the prompt fully?

Source: College Board

LEQ Essay Writing Checklist

-

Essay starts with context or background, which sets the scene

- Context flows into the thesis statement

- The introductory paragraph contains the context and thesis

- Thesis uses the same words as seen in the prompt

- Thesis answers the prompt and gives specific changes

- Thesis answers the prompt and gives specific continuities

- There are at least 5 paragraphs (more is OK)

- The first and second paragraphs address changes

- There are specific examples of changes given

- Analysis is provided explaining why there have been changes

- The third paragraph addresses continuities

- There are specific examples of continuities given

- The conclusion summarizes the essay’s thesis and main points

- Evidence is specific, and the writing is direct, clear and ties back

Practice for AP World History Free-Response Questions

The best way to practice for the AP World History FRQs is to use released questions from the College Board’s previous exams.

If you are enrolled in an AP World History class, your teacher will help you learn how to write effective responses and give you feedback on your writing. If you are studying independently, you should look at the released questions, sample student responses, and explanations of their scores available on the College Board website. By studying what makes high-scoring essays successful, you will be able to use the same strategies in your own essays. Be sure you are familiar with the rubrics that the graders use to score each essay. They will tell you how much information to include in your responses.

Practice writing essays at a slower pace at first to learn how to express your ideas effectively. Gradually, reduce the amount of time you spend practicing until you can write a quality essay in 40 minutes.

Boost your score with our comprehensive AP World History prep course, featuring a detailed study guide with full content coverage and an extensive QBank with exam-like questions to help you excel.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many FRQs are on the AP World History exam?

There are 2 FRQs on the AP World History exam: a long essay question (LEQ) and document-based question (DBQ).

How are FRQs graded?

The FRQs are graded by high school AP World History teachers and college professors who teach freshman-level History courses. The College Board provides rubrics that tell graders what to look for in successful essays. Essays are primarily graded on the quality of their ideas and not on the accuracy of grammar, punctuation, or spelling. Handwriting is not factored into the score. There are specially designated readers available to help read and score essays with unusually bad handwriting.

How long is the FRQ section of the AP World History exam?

Students have 1 hour and 40 minutes to complete FRQs on the AP World History exam.

Where can I get FRQs from past AP World History exams?

You can find questions from past exams on the AP Central website.

References

(2025). Section II: Document-Based Question and Long Essay. Exam Format. AP World History: Modern. Retrieved on January 8, 2025 from https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-world-history/exam

Read More About the AP World History exam

Answering MCQs appears simple, but the correct answer can differ by a small margin! Here, we will show you how to choose the correct answer for AP World History MCQs.

How to Write AP World History: Modern Short-Answer QuestionsNeed strategies for answering AP World History SAQs? We’re here to help, providing tips to answer each short-answer question to the point and help you ace this section.

AP World History Study Plan & TipsNeed a perfect study plan for AP World History: Modern? We’ll give you the essential strategies & resources to help you maximize your score on the APWH exam.

Best AP World History Prep Course ReviewConfused which APWH course to choose? Uncover the top prep courses with detailed reviews of their features, including expert-designed content, practice tests, and interactive tools.

AP World History Study Guide ComparisonDiscover the ideal AP World History study guide with our comprehensive comparison, featuring strengths, formats, price points, and the most effective tools for mastering every APWH unit.

How to Self-Study for AP World HistoryFind out how to effectively self-study for AP World History with step-by-step guidance, study plans, and tips for acing multiple-choice and free-response sections on the APWH exam.