AP English Language MCQ Section Format

There are 45 MCQs on the AP English Language exam, with 23 to 25 reading questions and 20 to 22 writing questions. You will have 60 minutes to complete this section, which makes up 45% of the exam score. Each question is weighted the same and assesses you on 1 or more of these 8 skills:

| Skill Category | Exam Weighting |

|---|---|

| Rhetorical Situation–Reading | 11%-14% |

| Rhetorical Situation–Writing | 11%-14% |

| Claims and Evidence–Reading | 13%-16% |

| Claims and Evidence–Writing | 11%-14% |

| Reasoning and Organization–Reading | 13%-16% |

| Reasoning and Organization–Writing | 11%-14% |

| Style–Reading | 11%-14% |

| Style–Writing | 11%-14% |

How to Study for the AP English Language Exam’s MCQs

The MCQs might be the most difficult section of the AP English Language and Composition exam because you must carefully examine the 4 choices per question and answer 45 questions within an hour. Here are 8 AP Lang MCQ tips and strategies to help you prepare for the readings and work quickly.

-

Start with the questions that seem the easiest.

Because all the questions are equally weighted, you should answer as many as you can in the time allowed, which means a good strategy is to work with the easy questions first. The writing questions are often the easiest to understand, so you may want to begin with them.

-

Annotate the reading passages as you read.

Make notes on the scratch paper while you are reading to call attention to patterns in word usage, summarize paragraphs and stanzas, and note rhetorical strategies used.

-

Assess the accuracy of all answer parts.

All parts of an answer must be accurate for the answer to be correct. Correct answers are fully backed by evidence, whereas incorrect ones are either partially or not supported. Exclude answers that lack complete support from the text.

-

Answer questions about the overall passage last.

Answer questions about specific lines/paragraphs first to help you figure out the argument presented in the passage. Pay attention to how the answers work together to clue you in on what the passage is arguing. Many times, the questions will help you see things about the passage that you wouldn’t necessarily spot. When you return to a question about the passage overall, you will likely have a better chance of choosing the correct answer.

-

Focus on the lines indicated in the question and surrounding details.

Many questions direct you to look at specific lines and paragraphs. Use only those lines to find the correct answer to the question. Avoid choosing an answer that relies on evidence from a different section of the passage or poem.

-

Focus on finding what makes each answer choice wrong.

Eliminating obvious incorrect answers will help you narrow down the choices and make a better guess, if necessary.

-

Study a few key terms.

Don't waste time studying a bunch of terms. Instead, ensure you know these words: exigence, qualify/qualification, concede/concession, underscore, and undermine.

-

Answer every question.

There is no penalty for incorrect answers, so you should always take your best guess even when you’re unsure. You only have to answer about 55% of the questions correctly to receive a passing score on the AP Lang MCQ section, so the odds are better if you record an answer for every question.

AP English Language Multiple-Choice Question Examples

Here are some sample AP English Language and Composition MCQs and answers explanations.

Passage 1

In this version of the dream, I'm in a suburban house at dusk, sitting at the kitchen table with my two cats perched in the window. Outside on the patio, a plastic laundry basket left on a picnic table keeps shifting its position: first, the long side faces us; then the short side; then the whole thing is upside down. Someone is out there tampering with the basket and trying to break into the house. I grab the cats and run upstairs for my car keys and phone, but at the top, there is another kitchen, and my father and stepmother are seated at the table. After all these years, it turns out, I'm still living in their house in Japan, a burden and an embarrassment they always said I would become to our family.

When I wake up with the cats next to me, it's 5 o'clock in the morning in another country, my father is long dead and my stepmother is out of my life, but summer is almost over, with school starting in a week. Every year around this time, sleep drags me back to a house that turns out to be my father's, or a math class I've been skipping where a big test is scheduled for tomorrow, or a foreign language class where everyone is speaking it and I don't even know what it is. My colleagues have anxiety dreams about going back to work, too, but their subconscious at least allows them to remain who they are. Lost in a warehouse while their students wait for them elsewhere, looking in vain through their briefcase for their books and notes, or standing at the podium in the wrong clothes or no clothes at all, they are still the teachers they have become. In my end-of-the-summer nightmares, I am a student failing a class, a grown woman unable to leave her childhood house.

My first full-time teaching job, some 30 years ago, was at a small Catholic college where the 18-year-olds in my general education classes copied each other's answers on pop quizzes (why else would a whole row of students write that Jason sailed with the Argonauts in search of a golden calf?), carried on their own conversations, ate their lunch, slept, looked through their vacation photos, and even painted their fingernails while I talked about heroism and hubris. The only positive comments I received on my semester-end evaluations were expressions of incredulity: "She really cared about literature!!!"; "She believed reading was important." Now I teach nonfiction workshops and literature courses in an MFA program. My students often say smart things I wish I had thought of and work hard to write and revise their essays and stories. So why am I having the same nightmares about going back to work?

After three months of staying home with my own writing, it's daunting to resume the schedule for a divided self. I'll need time to be a teacher, time to be a writer, and time to be everything else. The shift feels seismic: the landscape of my life is about to be rearranged again. I'll still be home more than any of my friends in our co-op building in DC. When I rush out the door on the two days I teach every week, it's past noon and everyone else has already put in a half day at work. But my friends don't see their jobs as museum curators, naturalists, political consultants, or human rights advocates as fundamentally separate from who they are.

My writing comes from everything I am and do, but the person who spends three hours reworking the same paragraph (and can't decide, at the end, whether she made it better or worse) is not one I would let loose even among my closest friends. The detachment I try to cultivate about my work—to revise what I can and scrap the rest—is the worst strategy possible for dealing with people. Even a minor house repair requires a different kind of patience or problem-solving skill than a writer's willingness to demolish what looks almost right but isn't and start over from scratch. Still, I've learned to keep the writer contained. I may become a relentless perfectionist for a few hours at my desk, but at the end of the day, I'm relieved to be my ordinary self, a low-key benign presence in any company. I didn't grow up in Japan for nothing. I'd much rather if people couldn't remember me after meeting me at a party, than if something I said or did was so unusual that it left an indelible impression on them.

During the summer, spending the afternoon on an essay and then going out with friends, taking a day off for a long bike ride or a museum visit, or even when my writing is interrupted by some crisis in our building—I'm the president of our co-op board—I can move easily between being a writer and being a friend, neighbor, co-op president, cyclist, art lover, or citizen at large. Balancing the two opposite aspects of myself—private and public, driven and relaxed—seems natural. Plenty of other people do the same in their own way. But when school starts and I have to be a teacher as well, the shift is so abrupt and startling that I'm forced to question whatever sense of balance or proportion I thought I had.

MCQ Example 1

The author introduces her essay by relating a version of her recurring dream (lines 1–7) primarily to

- confirm her audience's belief that dreams are significant

- praise the popular practice of reflecting on one's dreams

- establish an underlying anxiety she experiences

- examine the narrative pattern of the dreams she had in Japan

Correct Answer : C

How to approach:

Note the specific language the author uses to describe her dream and then draw a logical conclusion about what this introductory description contributes to the passage.

The author begins by stating "In this version of the dream," which implies that she has experienced a similar dream multiple times. She then describes someone "trying to break into" her house and running upstairs where she finds her "father and stepmother seated at the table." She recalls living with them in Japan, despite being an adult, and feeling like a "burden and embarrassment" like they said she would be.

Passage 2

In the early 1980s, originating in Japan, a new cultural artifact was introduced to the personal entertainment industry: the Walkman.1 Du Gay and others argue that the "Walkman" concept by itself had no meaning; however, the associations that were connoted by the "Walkman" gave it meaning. Du Gay et al. contend that "as well as being social animals, men and women are also [cultural] beings. They also assert that we use language and concepts to make sense of what is happening, even of events which may never have happened to us before, trying to 'figure out the world,' to make it mean something."

As a technological invention without functional value, the Walkman (or portable cassette player, until it gained wide following and recognition as the Walkman), was not transformative, but the connotations and interpretations that came attached to it were instrumental in its widespread use and acceptability across cultures. As Du Gay et al. suggest, notions associated with the Walkman included "Japanese", which stood for "superior, quality product," "technologically modern," "youth," "advancement" and other appeals that helped the "text"3 find its place and wide following. Its acceptability as a personalized, individualized means of listening to music, both including and excluding the surrounding environment, and therefore its popularity, also borrowed from concepts of mass information practices, i.e., advertising.

By constructing the ownership—promoting the concepts of enabling the individual to enjoy "private-listening-in-public-places" according to Du Gay et al., as well as reproduction and identification with the urban—the busy yet connected individual was propagated. The differences separating it from other forms of entertainment (for example, portable radios), and the specific market segment constructed through advertising (young, urban people) created a meaning for "the Walkman" and therefore transformed it from a simple technological device to a representation of a modern, "hip" urban youth. The role of advertising served to give it legitimacy, publicity and validity, and allowed individuals to conceptualize themselves as being part of that identity.

Personal preferences lead to personal choices, which in turn "globalize" works of art. In the age of mechanical production and globalization, art has begun to take on specific purposes: while the iPhone is a work of art, Apple must consider how the "text" will find a market niche and thereby be used all over the world, thereby altering the aura of an iPhone—or other similar phones—as a cultural object to emphasize its use. On the other hand, due to increasing globalization, the iPhone is a cultural text for the globalized, rather than just for the localized audience. Such artifacts then begin to enable us to conceptualize a truly global culture, since the iPhone is adaptable to different languages and uses in different parts of the world.

One other example deserves mention. The World Wide Web is, as far as cultural artifacts go, a "novel" invention, less than thirty years into its development, yet it has become one of the most visible "globalizers." The advent of Google has been one of the most technology-changing modern developments, redefining how communication affects transmission of specific and global cultural texts. One of its contributions to globalizing the local and localizing the global is scanning of out-of-print and non-copyrighted textbooks, journals and other media into a world-wide database, accessible by anyone who has a computer and an internet connection.

In developing the Google-Swahili language interface, Google collaborated with East African academics and Swahili scholars to verify maintenance of the language's integrity. The "global" came to the "local" to learn and adapt, and then the local became global after Google's interaction with the Swahili scholars. Suddenly, a language that was localized to Greater East Africa (in a few pockets of diasporic communities) found its way to global availability. Now, with a computer, one can learn Swahili from anywhere in the world, as is the case with many other languages. Thus, Swahili is re-defined through cultural artifacts that originated in the "West"—computers, internet, Google—and globalized to anyone that has access.

Does the global then affect the local and/or necessarily change the cultural purity of other cultures and their artifacts? While the Swahili language now "lives" in a different media, accessible to different people, the essence of the language and traditions has not changed; [this change] has, however, almost ensured longevity beyond the current speakers. This is illustrated by the case of preservation of the Latin language. Language preservation, especially for extinct and near-extinct language, ensures that they will be available in the future for study and/or re-introduction, even though some of the actual cultural practices may be lost forever.

Culture is not static; it is dynamic and adaptive. It "learns," "adapts" and "grows" to include "texts" that previously did not belong, integrating them and localizing their uses, thereby taking that which is global and localizing it and completing the circle. Similarly, the local often becomes globalized. In fact, tourists visiting foreign lands often visit the local markets in search of "texts" that are representative of the cultures in the foreign countries and bring them to their own foreign "local."

MCQ Example 2

In line 39, the author mentions that "one can learn Swahili anywhere in the world" to amplify his point about the

- evolution of linguistic tools typically used in language education

- significant role the World Wide Web has played in increasing globalization

- beneficial nature of sharing languages

- lack of progress in the spread of important cultural elements other than language

Correct Answer : B

How to approach:

Determine what point the author amplifies (emphasizes) by noting the claims in the related discussion. Select the choice supported by the author's claim that "one can learn Swahili anywhere in the world.

Because the World Wide Web helped increase globalization, some languages and their cultures have been preserved. Therefore, the author's statement that "one can learn Swahili anywhere in the world" helps to amplify his point about the significant role the World Wide Web has played in increasing globalization.

Passage 3

At the center of my earliest memories of writing is my maternal grandfather, a retired elementary school teacher who kept a journal and wrote haiku for the monthly poetry features of a local newspaper. In 1963, the year I started first grade, he gave me a small notebook. Inside its grey cover, each page was divided in two: the top half left blank for drawing, the bottom half lined for writing. My mother and I were spending the last few weeks of August with her parents in their rural village a half-day's train ride from our home in Kobe. Every evening after supper, my grandfather cleared the piles of books (history books, poetry books, dictionaries full of words I couldn't yet read) off the desk so I could sit kitty-corner from him to work on my "picture diary" while he composed his journal entry.

The walls around us displayed a dozen calligraphy scrolls on which my grandfather, as a young man, had copied classical Chinese poetry. The sentences he was writing in his notebook with his fountain pen looked nothing like the brush strokes that praised the permanence of the mountains, the swiftness of the wind. You didn't have to know how to read many Chinese pictographs to understand that those brush strokes represented 100-year-old trees and thousands of white herons and red-headed cranes flying over them. They were powerful dark splashes. Even the blank spaces between them looked grand. The private thoughts he put down in his notebook, by contrast, were tiny incisions: precise, mysterious, and complicated.

My grandfather and I worked in silence. I drew a picture of my mother and me swimming in the river and tried to find words to describe the minnows darting over the white rocks underwater (they could not appear in the picture; they were too small to be drawn), but the few sentences I managed to write were fat and clumsy, the opposite of how the minnows glittered in the sun. I longed to learn enough words to fill up the entire page and have them be the right words.

I only saw my grandfather three times, in secret, after my mother's death when I was 12 and my father's remarriage shortly after. Although I wrote to my grandparents every week, my father didn't allow them to respond so I didn't ever hear from them until I left my father's house to go to college in the States. My grandfather died a few years later while I was attending graduate school in Milwaukee. I walked to the bluff over Lake Michigan and looked at the expanse of steely blue water, not a drop of it touching any river or ocean he had ever seen.

One of the pictographs I learned in first grade was for river: three vertical strokes side by side, the curved one on the left veering away from the two straight lines that remained, center and right. I'm that single line that diverged from the source. Having spent my entire adulthood in the States, I no longer write in Japanese. All the same, when summer is almost over and the earlier arrival of dusk tricks my mind into reconstructing my father's house in my sleep, I need to find my way back to the other house of my memory where my grandfather gave me a notebook for my first journal.

The journal is the most private form of writing. My grandfather and I didn't read each other's words as we sat thinking and writing, with the crickets practicing their autumn songs out in the garden. In haiku, many of the things I associated with summer—crickets, shooting stars, melons ripening on the vine—were considered to be signs of autumn. My grandfather and I would not have much time together. The noise from the hundreds of wings and legs wrapped around our concentration as we worked in our parallel solitude, which would continue to be our collaboration. He showed me that writing is a discipline each must pursue alone, and yet he let me in on his practice of it by allowing me to share a small corner of his desk. He moved his books aside to make room for me. I don't fear the double calling of writing and teaching when I remember that I'm continuing a family tradition.

MCQ Example 3

In the first paragraph, the author describes her notebook (lines 2–8) in order to

- reflect on the difference between the author and her family

- situate the reader in Kobe, Japan

- introduce ideas about writing, admiration, and influence

- set up the theme of secret communication

Correct Answer : C

How to approach:

Summarize the description of the author's notebook and examine its relationship to the rest of the passage to decide what important idea the author introduces or reinforces through it.

In these lines, the author describes the notebook given to her by her grandfather and how she would sit near him and work on her "picture diary" in that notebook, while he wrote in his journal. The author mirrors his actions and, at the end of the passage, describes how she has followed in his footsteps as a writer and a teacher. Therefore, the author describes her notebook to introduce ideas about writing, admiration, and influence.

Passage 4

The journey had been final. And it was only on this trip to India that I was to see how complete a transference had been made from eastern Uttar Pradesh to Trinidad, and that in days when the village was some hours' walk from the nearest branch-line railway station, the station more than a day's journey from the port, and that anything leading up to three months' sailing from Trinidad. In its artefacts India existed whole in Trinidad. But our community, though seemingly self-contained, was imperfect. Sweepers we had quickly learned to do without. Others supplied the skills of carpenters, masons, and cobblers. But we were also without weavers and dyers, workers in brass and makers of string beds. Many of the things in my grandmother's house were therefore irreplaceable. They were cherished because they came from India, but they continued to be used and no regret attached to their disintegration. It was an Indian attitude, as I was to recognize. Customs are to be maintained because they are felt to be ancient. This is continuity enough; it does not need to be supported by a cultivation of the past, and the old, however hallowed, be it a Gupta image or a string bed, is to be used until it can be used no more.

To me as a child the India that had produced so many of the persons and things around me was featureless, and I thought of the time when the transference was made as a period of darkness, darkness which also extended to the land, as darkness surrounds a hut at evening, though for a little way around the hut there is still light. The light was the area of my experience, in time and place. And even now, though time has widened, though space has contracted and I have travelled lucidly over that area which was to me the area of darkness, something of darkness remains, in those attitudes, those ways of thinking and seeing, which are no longer mine. My grandfather had made a difficult and courageous journey. It must have brought him into collision with startling sights, even like the sea, several hundred miles from his village; yet I cannot help feeling that as soon as he had left his village he ceased to see. When he went back to India it was to return with more things of India. When he built his house he ignored every colonial style he might have found in Trinidad and put up a heavy, flat-roofed oddity, whose image I was to see again and again in the ramshackle towns of Uttar Pradesh. He had abandoned India; and, like Gold Teeth, he denied Trinidad. Yet he walked on solid earth. Nothing beyond his village had stirred him; nothing had forced him out of himself; he carried his village with him. A few reassuring relationships, a strip of land, and he could satisfyingly re-create an eastern Uttar Pradesh village in central Trinidad as if in the vastness of India.

We who came after could not deny Trinidad. The house we lived in was distinctive, but no more distinctive than many. It was easy to accept that we lived on an island where there were all sorts of people and all sorts of houses. Doubtless they too had their own things. We ate certain food, performed certain ceremonies and had certain taboos; we expected others to have their own. We did not wish to share theirs; we did not expect them to share ours. They were what they were; we were what we were.

Excerpt from AN AREA OF DARKNESS by V.S. Naipaul. Copyright © 1964 by V.S. Naipaul, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

MCQ Example 4

In lines 13–15, the repetition of the word "darkness" primarily serves to

- reinforce a statement by providing a figurative description

- qualify an argument by acknowledging an exception to it

- characterize contrasting perspectives as equally valid

- exemplify a generalization using a historical case

Correct Answer : A

How to approach:

Restate the surrounding discussion to determine the purpose of repeating the word "darkness."

The author reflects on his unfamiliarity with India during his childhood and characterizes this unfamiliarity as "darkness." To help readers better understand his point, he then makes a figurative comparison between that "darkness" and how people struggle to see anything in the dark at night. Therefore, the repetition of "darkness" serves to reinforce a statement by providing a figurative description.

How to Practice for AP English Language Multiple-Choice Questions?

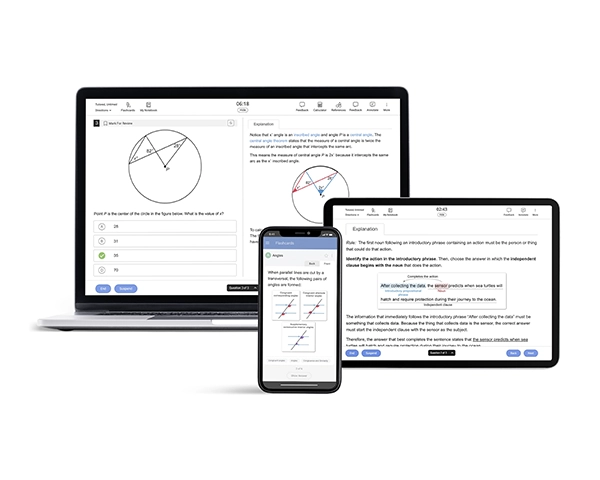

The best way to improve your AP English Lang MCQ score is to follow our AP Lang MCQ strategies and practice as many questions as possible. You will become familiar with the information and be more comfortable answering questions – even if you have to make a guess. Answer questions at your own pace first. As you develop your confidence and skill, practice answering questions at a pace similar to what you will experience on the exam: a little over a minute per question.

Our AP English Language and Composition prep course can help you get familiar with AP-level MCQs. With over 600 practice questions, our QBank provides explanations to help you understand why answers are correct or incorrect and our study guide offers a comprehensive coverage of all the units, topics, and course skills.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many multiple-choice questions are on the AP English Language exam?

There are 45 MCQs and 3 FRQs on the AP English Language exam. The MCQ section is worth 45% of the score, and the FRQ is worth 55%.

How are AP English Language multiple-choice questions graded?

An automated computer system grades the AP Lang multiple-choice questions. You receive a point for each question you answer correctly.

Are AP English Language multiple-choice questions hard?

Many students do well on the multiple-choice section of the AP English Language exam. The hardest part is understanding the questions. That’s why familiarizing yourself with the format of the questions is important. We recommend following our AP Lang MCQ tips and practicing with resources that closely mimic the style and content of the exam to achieve your desired score.

Are AP English Language multiple-choice questions like SAT questions?

The AP English Language reading MCQs are similar to the ones on the SAT®. However, the SAT includes a prose fiction reading passage, while the AP English Language exam only includes prose nonfiction passages. There is some similarity between the AP English Language writing questions and the SAT writing questions. For example, both ask you to combine sentences and choose evidence to support a claim. However, SAT MCQs ask about grammar and punctuation, whereas the AP English Language exam does not.

Where can I get past AP English Language exam multiple-choice questions?

The College Board® does not typically make its AP English Language and Composition MCQs from past exams available publicly. Hence, UWorld’s QBank is the best way to practice for the AP Lang MCQ section.

References

(2024). Exam Format. AP English Language and Composition. College Board. Retrieved on January 15, 2025 from https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-english-language-and-composition/exam

(2024). Course Skills. AP English Language and Composition. College Board. Retrieved on January 15, 2025 from https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-english-language-and-composition

Related Topics

Do you have difficulty answering AP English Language free-response questions (FRQs)? Check out sample FRQs and get expert advice to excel on this exam section!

AP English Language Study Plan & TipsFind out how to study for the AP Language and Composition exam with expert tips on analyzing passages, crafting high-scoring essays, and managing your schedule.

AP English Language Exam FormatDon’t get overwhelmed with the AP Lang exam structure. Get a clear picture of the AP English Language and Composition exam format question types, weights, and more!

Best AP English Language Study Guide ComparisonDiscover expert insights into Kaplan, Barron's, Princeton Review, and UWorld. Learn how each resource compares to help you choose the best fit.

Best AP English Language Prep Course ReviewDiscover the best AP Eng Lang prep courses available. Compare key features, pricings, reviews, and benefits to select the course that best fits your learning.

How to Self-Study for AP English LanguageWant to ace AP English Language & Composition on your own? Follow this expert self-study guide with tips, tricks, and tools to prepare effectively for the exam.