The Reading section of the ACT consists of 40 multiple-choice questions (MCQs) to be answered in 35 minutes, giving you approximately 52 seconds per question. There are 3 long passages and one paired set with 2 short passages that must be read together.

ACT Reading questions assess your ability to identify main ideas, interpret specific details, understand cause-effect relationships, grasp a sequence of events, and make comparisons between elements. Your ACT Reading score is reported in these categories:

- Key Ideas and Details (52-60%)

- Craft and Structure (25-30%)

- Integration of Knowledge and Ideas (13-23%)

General Tips to Succeed on ACT Reading Section

Approaching the ACT Reading section involves a systematic approach that includes developing a strong understanding of foundational concepts, utilizing resources such as UWorld’s ACT Reading practice tests, and practicing with timed tests to familiarize yourself with ACT Reading question types. You can also strengthen your prep by using our comprehensive ACT Question Bank, which covers all passage types and question styles.

Having a structured study plan will help you stay focused and organized in your preparation. Use our ACT Reading study guide to create a study plan that sets realistic goals for each of your study sessions and ensures you cover everything thoroughly before the exam.

Here are some ACT Reading strategies to help you prepare:

-

Skim through the ACT Reading passages

Glance at titles, subheadings, and introductory info to get a sense of the passage’s structure and content.

-

Carefully read the questions

Break down each question to understand what it’s asking before jumping into answer choices.

-

Analyze graphs, charts, and tables

Some passages include visual elements such as graphs, charts, and tables. Always review labels, headings, and data points carefully.

-

Answer all ACT Reading questions

There is no penalty for wrong responses. Eliminate unlikely choices and make educated guesses.

-

Highlight key information

Use underlining, circling, or mental notes to focus on important facts and keywords. Always rely on evidence from the passage — not your prior knowledge.

-

Skip and revisit difficult questions

Don’t let 1 question eat up your time. Mark and return to it later if needed.

4 Different Types of Passages You’ll Encounter

There are 4 kinds of ACT Reading passages — Literary Narrative and Prose Fiction, Natural Science, Social Studies, and Humanities — all of which are covered in our ACT Practice Test PDF with Answers.

Literary Narrative and Prose Fiction Passages

These passages are drawn from fictional works like novels or short stories. They often include character development, themes, symbolism, and figurative language.

Strategies to Ace Literary Narrative and Prose Fiction Questions

Here are a few tips to understand Literary Narrative and Prose Fiction passages:

-

Identify the passage’s main idea and themes

Understand how the characters, plot, and setting support the passage's central theme.

-

Analyze the character(s)

Examine motivations, dialogue, and development to grasp their impact on the narrative.

-

Understand the plot structure

Recognize the elements of storytelling — exposition, rising action, climax, etc. — to follow the flow of events.

Literary Narrative and Prose Fiction Questions Examples

Passage

This work is adapted from Barry Lyndon by William Makepeace Thackeray, originally published in 1844.

Barry was only twelve years old when he was sent to Castle Brady, his family's ancestral home. Although he had lived with his widowed mother in her small, impoverished cottage for the past three years, he marched through the doors of the castle with a proprietary air, for he had been told his entire life that he descended from noble families. Once inside he walked with deliberate, slow steps while discreetly eyeing his surroundings in an effort to mask his admiration and eagerness, for his pride was such that he did not want to acknowledge the lowly state to which his mother had fallen after the death of his father. Yet, he could not help but admire the gilded frames surrounding the portraits of his ancestors and the elaborate armorial trophies attesting to his family's noble heritage, as well as the many scholarly degrees. His chest filled with pride; he belonged to these people. Fortunately, Barry had a practical side, which insisted that displays of wealth, privilege, and education do not indicate superiority, a notion which often resulted in skirmishes with his cousins, who did not consider Barry an equal.

Barry dreamed of becoming a gentleman, so during his younger years, Barry's mother introduced him to the more noble arts. It was their hope that one day he would gain the status his father's family once enjoyed; however, her meager allowance could not provide him a proper education, so he was sent to Castle Brady to live with his uncle's family. Once there, he did not venture back to the gate to plead with his mother to take him home, nor did he meekly thank his uncle for taking him in, as might be expected. Instead, he pictured himself in the future dancing in the grand ballroom, taking meals with the family in the formal dining room, and telling spectacular stories to an enthralled audience.

How could a destitute young boy, a budding chameleon, enter a castle in the manner of nobility and feel completely at home as if he had been knighted by King Arthur? I can only imagine what the future holds for a boy this full of self-assurance and determination.

***

The very first day at Castle Brady my trials may be said, in a manner, to have begun. My cousin, Master Mick, a huge monster of nineteen (who hated me, and I promise you I returned the compliment), insulted me at dinner about my mother's poverty, and made all the girls of the family titter. So, when we went to the stables, where Mick always went for his pipe of tobacco after dinner, I told him a piece of my mind, and there was a fight for at least ten minutes, during which I stood to him like a man, and blacked his left eye, though I was myself only twelve years old at the time. Of course, he beat me, but a beating makes only a small impression on a lad of that tender age, as I had proved many times in battles with the ragged Brady's Town boys before, not one of whom, at my time of life, was my match. My uncle was very much pleased when he heard of my gallantry, and I went home that night not a little proud, let me tell you, at having held my own against Mick so long and stashed away the celebratory ale awarded by my uncle.

At Castle Brady my learning was not neglected, for I had an uncommon natural genius for many things, and soon topped in accomplishments most of the persons around me. I had a quick ear and a fine voice, which my mother cultivated to the best of her power, and she taught me to step a minuet gravely and gracefully, and thus laid the foundation of my future success in life. In the matter of book-learning, I had always an uncommon taste for reading plays and novels, as the best part of a gentleman's polite education. As for your dull grammar, and Greek and Latin and stuff, I have always hated them from my youth upwards, and said, very unmistakably, I would have none of them.

This I proved pretty clearly at the age of thirteen, when my mother came into a legacy of much money and thought to employ the sum on my education and sent me to Doctor Tobias Tickler's famous academy at Ballywhacket. But six weeks after I had been consigned to his reverence, I suddenly made my appearance again at Castle Brady, having walked forty miles from the odious place. So, six weeks was all the schooling I ever got. And I say this to let parents know the value of it; for though I have met, throughout my many years, more learned book-worms in the world, especially a great hulking, clumsy, blear-eyed old doctor, whom they called Johnson, I may say for myself that I have seldom found my equal. "Sir," said I once to Mr. Johnson, "you fancy you know a great deal more than me, because you quote your Aristotle and your Pluto; but can you tell me which horse will win at Epsom Downs next week? —Can you run six miles without breathing? —Can you shoot the ace of spades ten times without missing? If so, talk about Aristotle and Pluto to me."

1. Barry Lyndon by William Makepeace Thackeray. Used under public domain. Licensed by UWorld.

Question

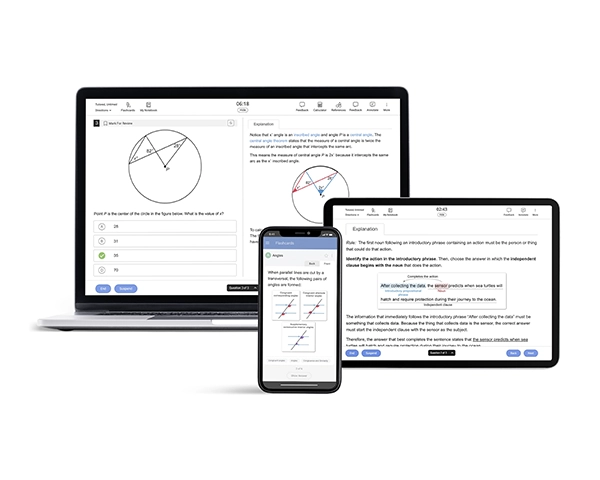

The passage can most reasonably be described as being divided into two sections that, taken together, explore:

| A. Barry's first experiences in Castle Brady as told from two perspectives, one being that of Barry's uncle. | ||

| B. two accounts of Barry's time at Castle Brady, both presented from the perspective of Barry as a young child. | ||

| C. Barry's relationship with his family, presented from the perspective of two of Barry's relatives. | ||

| D. elements of Barry's move to Castle Brady as told from two perspectives, one being Barry as an adult. |

Explanation

Paragraph 1: Barry was only twelve years old when he was sent to Castle Brady, his family's ancestral home.

P2: [H]e did not venture back to the gate…nor did he meekly thank his uncle…he pictured himself....

***

P4: The very first day at Castle Brady my trials may be said, in a manner, to have begun.

P6: And I say this to let parents know the value of it; for though I have met, throughout my many years, more learned book-worms in the world, especially a great hulking, clumsy, blear-eyed old doctor, whom they called Johnson, I may say for myself that I have seldom found my equal..

The passage is divided into two parts, separated by (***), that must be considered together when answering the question. Scan each section and identify details to help you answer the question.

To understand what you need to identify, read the answer choices. Each has two parts, and both must be accurate: the main idea of the passage and the perspective from which both parts are told.

| P1–3 | "Barry was only twelve years old when he was sent to the Castle Brady." Use of the word "he" tells you this section is from the perspective of someone other than Barry. |

| P4–6 | This section also discusses his move("The very first day of Castle Brady…"), and because of the repeated words "my" and "I," you can determine the section is written from Barry's own perspective. This section also says Barry has finished schooling and lived "many years," so he is an adult. |

Taken together, the sections explore elements of Barry's move to Castle Brady as told from two perspectives, one being Barry as an adult.

(Choices A & B) Although both sections describe Barry's first experiences in Castle Brady, neither follows the perspective of Barry's uncle or of a young child.

(Choice C) Although Barry's family is mentioned in both sections, neither is told from the perspective of a relative.

Things to remember:

When a question does not state exactly what you must identify, read the answer choices to determine what to focus on while skimming the passage.

Passage

This work is a derivative of "A Son of the Middle Border" by Hamlin Garland.

For a few days my brother and I had little to do other than to keep the cattle from straying, and we used our leisure in becoming acquainted with the region round about.

Iowa burned deep into our memories, this wide, sunny, windy country that was our new home. The sky so big, and the horizon line so low and so far away, made this new world of the plain more majestic than the world of the Wisconsin coulee. The grasses and many of the flowers were also new to us. On the uplands the herbage was short and dry and the plants stiff and woody, but in the swales the wild oat shook its quivers of barbed and twisted arrows, and the crow's foot, a tall and sere plant, bowed softly under the feet of the wind, while everywhere, in the lowlands as well as on the ridges, the bleaching white antlers of by-gone herbivora lay scattered, testifying to the herds of deer and buffalo which once fed there. We were just a few years too late to see them.

To the south the sections were nearly all settled upon, for in that direction lay the county town, but to the north and on into Minnesota rolled the unplowed sod, the feeding ground of the cattle, the home of foxes and wolves, and to the west, just beyond the highest ridges, we loved to think the bison might still be seen.

The cabin on this rented farm was a mere shanty, a shell of pine boards, which needed re-enforcing to make it habitable. One day my father said, "Well, Hamlin, guess you'll have to run the plow-team this fall. I must help neighbor Button wall up the house and I can't afford to hire another man." This seemed a fine commission for a lad of ten, and I drove my horses into the field that first morning with a manly pride which added an inch to my stature. I took my initial "round" at a "land," which stretched from one side of the quarter section to the other, in confident mood. I was grown up! But alas! My sense of elation did not last long. To guide a team for a few minutes as an experiment was one thing—to plow all day like a hired hand was another. It was not a chore. It was a job. It meant moving to and fro hour after hour, day after day, with no one to talk to but the horses. It meant trudging eight or nine miles in the forenoon and as many more in the afternoon, with less than an hour off at noon.

Although strong and active, I was rather short, even for a ten-year-old, and to reach the plow handles I was obliged to lift my hands above my shoulders; and so with the guiding lines crossed over my back and my worn straw hat bobbing just above the cross-brace I must have made a comical figure. At any rate, nothing like it had been seen in the neighborhood, and the people on the road to town, looking across the field, laughed and called to me, and neighbor Button said to my father in my hearing, "That chap's too young to run a plow," a judgment which pleased and flattered me greatly.

But plowing soon became tedious. The flies were savage, especially in the middle of the day, and the horses drove badly, twisting and turning in their despairing rage. Their tails were continually getting over the lines, and in stopping to kick the flies from their bellies, they often got astride the traces, and in other ways made trouble for me. Only in the early morning or when the sun sank low at night were they able to move quietly along their ways. The soil was "ideal," the kind my father had been seeking, a smooth, dark, sandy loam, which made it possible for a lad to do the work of a man. Often the share would go the entire "round" without striking a root or a pebble as big as a walnut, the steel running steadily with a crisp craunching ripping sound which I rather liked to hear. In truth the work would have been quite tolerable had it not been so long drawn out. Ten hours of it even on a fine day made about twice too many for a boy.

On certain days nothing could cheer me. When the bitter wind blew from the north, and the sky was filled with wild geese racing southward, with swiftly hurrying clouds, winter seemed about to spring upon me. At such times I suffered from cold and loneliness—all sense of being a man evaporated. I was just a little boy, longing for the leisure of boyhood. Finally the day came when the ground rang like iron under the feet and a bitter wind, raw and gusty, swept out of the northwest, bearing gray veils of sleet. Winter had come! Work in the furrow had ended.

1. "A Son of the Middle Border" by Hamlin Garland, used under public domain. Licensed by UWorld.

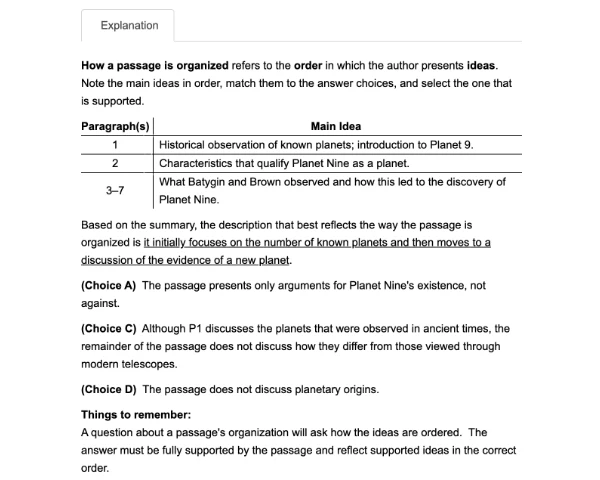

Question

Based on the passage, which of the following statements represents one of the narrator's typical experiences with plowing the field all day?

| A. The narrator and a few friends who had their own horses would plow the fields together. | ||

| B. Sometimes the narrator would plow with the horses, but other days he would plow without them. | ||

| C. When the narrator plowed with the horses, he would be the only person out there. | ||

| D. The narrator would plow with the adults, since they were better at plowing than he was. |

Explanation

Paragraph 4: It meant moving to and fro hour after hour, day after day, with no one to talk to but the horses.

When asked questions based on the passage, locate the topic in the passage, note the details, and select the answer supported by those details.

P4 discusses the narrator's experiences plowing the field "day after day." He notes he worked "hour after hour…with no one to talk to but the horses." Therefore, when the narrator plowed with the horses, he would be the only person out there.

(Choice A) The passage does not mention friends helping plow the field, so this answer is unsupported.

(Choice B) The narrator mentions working "day after day" with only the horses to talk to, so there is no evidence that he would plow without those animals. In addition, the horses pulled the plow, which he wouldn't be able to do on his own.

(Choice D) Because the only two adults mentioned (his father and Button) were busy working to "wall up the house," the work fell to the narrator. The passage provides no evidence of adults helping with the plowing.

Things to remember:

Answers to questions based on the passage are stated directly in the text, even if worded differently. Locate the subject matter, summarize the details, and match these details to the answer choices.

Natural Science Passages

These passages cover topics such as biology, chemistry, astronomy, ecology, medicine, and technology. They often include data or visual aids.

Strategies to Ace Natural Science Questions

Here are a few tips to conquer natural science passages:

-

Actively engage with visual aids

Study graphs, tables, and charts carefully for data trends.

-

Practice interpreting data

Look for cause-and-effect relationships and draw conclusions from numerical or experimental information.

-

Pay attention to cause-and-effect relationships

Understand how scientific methods or changes in variables affect outcomes.

Natural Science Questions Examples

Passage

This work is adapted from “The Andromeda Galaxy” by The Science Archives.

The Andromeda galaxy (also known as M31) was first observed in 964 A.D. by Persian astronomer Abb al-Rahman al-Sufi who described it as a "nebulous smear." In later years, its description evolved to that of an "island universe" by Immanuel Kant. This was supported by later scientists who believed that spiral nebulae were independent galaxies and that Andromeda was surrounded by an ocean of stars and gasses. Using the measured velocities of its stars, Ernst Opik theorized that Andromeda was a nebula approximately 1.5 million light-years from our own galaxy.

However, as new information was gathered, the island metaphor broke down. First, there are other galaxies in its neighborhood, so, at best it is one of a chain of islands. At worst, Andromeda is a nebulae eater that has likely absorbed several other smaller galaxies earlier in its evolution; scientists believe that a galactic merger roughly 100 million years ago is responsible for the counter-rotating disk of gas. In addition, scientists have found that Andromeda is not simply a spiral galaxy but a barred spiral galaxy with the bar located along its long axis. Envision a wheel with a round hub in the middle and spokes branching outward. However, even that image broke down as scientists analyzed the cross-sectional shape of the galaxy, which demonstrated a pronounced, S-shaped warp rather than just a flat disk. Two of its spiral arms are tightly wound (described as resembling beads on a string by Walter Baade) but widely spaced around its nucleus when compared to the Milky Way's arms, and the radius of these arms is approximately 45,000 light-years across. In the hub, scientists have spotted all the signs of a 100-million-solar-mass black hole. Orbiting around that black hole are older red stars and younger blue stars.

As more was observed, scientists began to wonder why the galaxy contained an S-shaped warp rather than maintaining the neater wheel shape. They found that a possible cause of such a complication could be the gravitational interaction with the nearby satellite galaxies. In fact, scientists theorize that the M33 Galaxy is responsible for some warp in Andromeda's arms, though more precise distances and radial velocity—a method of locating a planet by tracking its gravitational pull on a star using the star's color signature—are required to determine the accuracy of such a theory. Data gathered in 1998, images from the European Space Agency's Infrared Space Observatory, were the first to indicate that the Andromeda Galaxy may not be a three-dimensional wheel after all; its overall form may be transitioning into a ring galaxy, transforming into something like a three-dimensional target with a bulls-eye nucleus in the middle and rings spreading out from there. Images reveal that the gas and dust within the galaxy currently form several overlapping rings, with a particularly prominent ring—nicknamed the ring of fire by some astronomers—formed at a radius of 32,000 light-years from the core. Scientists believe that this ring is hidden from visible light images of the galaxy because it is composed primarily of cold dust, and the majority of the star formation taking place in the Andromeda Galaxy is concentrated there.

Although some astronomers dismiss the findings as circumstantial at best, most others agree that closer examination of the inner region of the Andromeda Galaxy using the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes revealed valuable information about how galaxies behave. They uncovered a smaller dust ring that is believed to have been caused by the interaction with M32 more than 200 million years ago and now likely contains what is left of M32. Scientists' simulations show that the smaller galaxy passed through the disk of the Andromeda Galaxy along the latter's polar axis. Much like the winner of a game of marbles who captures all of their opponent's marbles after knocking them out of the circle, this collision captured more than half of M32's mass and created the ring structures. It is the coexistence of the long-known large ring-like feature in the gas of Andromeda, together with this newly discovered inner ring-like structure, offset from the barycenter, that suggested a nearly head-on collision with the satellite M32.

The Andromeda Galaxy, like the Milky Way, has satellite galaxies, consisting of 14 known dwarf galaxies. In addition to M32, M110 also appears to be interacting with the Andromeda Galaxy. Astronomers have found a stream of metal-rich stars that appear to have been stripped from these satellite galaxies, and M110 contains a dusty lane, which may indicate recent or ongoing star formation. In 2006, it was discovered that nine of the satellite galaxies lie on a plane that intersects the core of the Andromeda Galaxy; they are not randomly arranged as would be expected from independent interactions. This arrangement isn't enough to prove the cause in itself, but it's solid circumstantial evidence indicating a common tidal origin and direction for the satellites.

1. This work, "Observing Andromeda," is a derivative of "Andromeda Galaxy" by The Science Archives, used under CC-BY. "Observing Andromeda" is licensed under CC-BY SA by UWorld.

Question

The author primarily refers to a nebulae eater in order to:

| A. point out the instability of Andromeda's pattern of acquiring new stars. | ||

| B. assist in expressing the insufficient nature of the island metaphor. | ||

| C. highlight the nature of the rotating disk that makes Andromeda unique. | ||

| D. explain how the hidden ring has recently become visible through new images of the galaxy. |

Explanation

P2: However, as new information was gathered, the island metaphor broke down…. At worst, Andromeda is a nebulae eater that has likely absorbed several other smaller galaxies earlier in its evolution….

To determine why an author refers to Andromeda as a nebulae eater, note the details of that discussion and use that information to draw a logical conclusion about why it was included.

P2 states that new information was gathered about Andromeda and the "island metaphor broke down." In fact, scientists hypothesized that Andromeda was more likely a "nebulae eater" that had "absorbed several other smaller galaxies." Therefore, the author primarily refers to a nebulae eater in order to assist in expressing the insufficient nature of the island metaphor.

(Choice A) The context does not mention any instability in Andromeda's pattern of acquiring new stars, so that reason couldn't have motivated the author to use this reference.

(Choice C) Although the context discusses Andromeda's absorption of other galaxies as being "responsible for [its] counter-rotating disk of gas," there is no mention of Andromeda being unique (the only one of its kind).

(Choice D) The visibility of Andromeda's hidden ring is not discussed until P3 and it is not connected to Andromeda's status as a nebulae eater.

Things to remember:

Locate the subject, summarize its details and its context, and use this information to select the supported answer when asked why an author refers to something.

Passage

This work is adapted from the article "'Anternet' Algorithm Works Like the Web" by Bjorn Carey-Stanford (©2012 by Futurity).

When Deborah Gordon, a Stanford biologist, determined how the harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex barbatus) she had been observing decided when to send out more ants to get food, she called across campus to Balaji Prabhakar, a computer science professor and expert on how files are transferred on a computer network. At first, he didn't see any overlap between his and Gordon's work, but inspiration would strike soon.

"It occurred to me, 'Hey, this is almost the same as Internet protocols—how they discover how much bandwidth is available for transferring a file!'" Prabhakar says. "The algorithm the ants were using to discover how much food there is available is, amazingly, essentially the same as that used in the Transmission Control Protocol" (TCP).

TCP is an algorithm that manages data congestion on the Internet by ensuring that data do not go out unless the system receives feedback indicating there is enough bandwidth to receive that data. The system does this by first sending out a large amount of data to determine if it all goes through. It turns out that harvester ants behave nearly the same way when searching for food.

Harvester ants searching for food in the desert undergo desiccation, and the ants obtain water from metabolizing the fats in the seeds they eat. Thus, a colony must spend water to obtain both water and food. The first decision the ants make, as Gordon learned, is whether to leave the nest at all. Most colonies use more than one foraging trail on a given day. Approximately 50 patrollers search the area before foragers emerge, depositing pheromones on sections of the nest mound that lead to the beginning of a foraging trail. These deposits provide a foraging direction but do not extend all the way to food sources, which could be far away. Removal experiments show that the return of these patrollers to the nest stimulates the beginning of foraging. If patrollers are prevented from returning, all activity stops for at least one hour.

The foragers travel a trail extending up to 20 meters from the nest. Each ant leaves the trail to search for food individually. When a forager finds a seed, it goes back to the trail to return to the nest. Once at the nest, it taps antennae with inactive foragers that are waiting in a narrow entrance tunnel. This antennal communication tells the waiting ants that the returning forager successfully located seeds. A forager ant does not leave the nest until it has reached a threshold rate of interactions, beyond which the benefits of searching are likely to be greater than the costs.

Prabhakar wrote an algorithm attempting to predict foraging behavior when Gordon manipulated the rate of forager return. Forager return rate corresponds to food availability, because foragers almost always continue to search until they find food, then immediately bring it back to the nest. The more resources are available, the less time foragers spend searching and the quicker they return to the nest. If, however, ants begin returning slower and empty handed—as in removal experiments in which Gordon and Prabhakar deprived foragers of their food and then delayed them from returning to the nest for one hour by placing them inside a clear box—the search is slowed, and perhaps called off. Therefore, Gordon and Prabhakar's study shows that the moment-to-moment regulation of foraging depends on positive feedback from returning foragers, who stimulate the outgoing foragers to leave on the next trip.

"Ants have discovered an algorithm that we know well, and they've been doing it for millions of years," Prabhakar says. He believes that had this discovery been made before TCP was written, harvester ants very well could have influenced the design of the Internet.

The ants also followed two other phases of TCP. One phase, known as slow start, describes how a source sends out a large wave of data at the beginning of a transmission to gauge bandwidth; similarly, when harvester ants begin foraging, they send out many foragers to scope out food availability before scaling up or down the rate of outgoing foragers.

Another protocol, called time-out, occurs when a data transfer link breaks or is disrupted, and the source stops sending packets. Similarly, when foragers are prevented from returning to the nest for more than 20 minutes, no more foragers leave the nest. Gordon conducted field experiments to examine how quickly a colony adjusts to a decrease in the rate of forager return by slowing down foraging activity. When researchers caused a three- to five-minute reduction in the forager return rate by placing ants in a clear box, foraging activity decreased within two to three minutes and then recovered within five minutes after the interference ended. This indicates that whether an inactive forager leaves the nest on another trip depends on its very recent experience of the rate of forager return. From an evolutionary perspective, harvester ants have evolved a highly efficient system.

Question

The passage suggests that which action of a forager most strongly influences an inactive forager to leave the nest in search of food?

| A. The forager tapping its front legs against the ground | ||

| B. The forager bringing a seed back to the nest | ||

| C. The forager leaving a pheromone trail | ||

| D. The forager returning to the nest without food |

Explanation

P6: Forager return rate corresponds to food availability…. The more resources are available, the less time foragers spend searching and the quicker they return to the nest…. Therefore, Gordon and Prabhakar's study shows that the moment-to-moment regulation of foraging depends on positive feedback from returning foragers, who stimulate the outgoing foragers to leave on the next trip.

To determine what the passage suggests about which forager action most strongly influences inactive foragers to leave the nest, note the details and pick the answer that most closely matches those details.

P6 discusses how ants decide when to leave the nest, and that "forager return rate" depends on food availability. P6 also says positive feedback (ants finding food) triggers action in ants, and the "less time foragers spend searching [for food] and the quicker they return to the nest." Therefore, the passage suggests that the forager action that most strongly influences an inactive forager to leave is the forager bringing a seed back to the nest.

(Choice A) P5 states that returning foragers communicate their success by tapping their antennae with those of inactive foragers, not by tapping their front legs against the ground.

(Choice C) P4 indicates that patroller ants, not foragers, leave pheromone trails.

(Choice D) P6 mentions that the search for food is slowed or stopped if foragers begin returning without food, so this action would not influence inactive foragers to leave the nest in search of food.

Things to remember:

When asked what the passage suggests about a topic, note the details regarding that topic and choose the answer that best fits those details.

Social Studies Passages

Subjects include archaeology, political science, history, economics, and sociology. These passages often discuss societal norms, political structures, and historical developments.

Strategies to Ace Social Studies Questions

Here are a few tips to tackle social studies passages:

-

Analyze Historical Documents and Texts

Interpret excerpts from speeches or letters in historical context.

-

Consider Multiple Perspectives

Recognize and evaluate different viewpoints to fully understand the passage.

-

Review Social Science Terminology

Knowing key political and economic terms improves comprehension.

Social Studies Questions Examples

Passage

This work is adapted from "Geography of the Great Plains" (© National Park Service 2017).

In the sixteenth century, Spanish explorers first saw the vast expanse of the grasslands in the interior of North America, calling the region a "sea of grass." Subsequent French colonists called the grasslands "prairies," which comes from the French word meaning "large meadows." Even though the term stuck, in many ways prairie is certainly an understatement. In the colonial period, the grass sometimes stood taller than a man, and in many places a horseman had to stand on his horse's back to get his bearings. The tops of undulating grasses rippled in the breeze like the waves of the ocean, stretching like an unbroken expanse of water to the horizon. The plains were home to Native Americans for tens of thousands of years and before white incursions. Before the widespread white settlement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the prairies covered more land of what is now the United States than did any other kind of vegetation—more area than the green deciduous forests of the east that spread from Maine to Georgia; more area than the deserts of the southwest; more area than the boreal forests of the north. Walt Whitman wrote of the prairie that it is "North America's characteristic landscape," and "while less stunning at first sight" than Yosemite, Niagara Falls, and Yellowstone, the Great Plains "fills the aesthetic sense fuller, and precedes all the rest."

A description of the way the plains looked when the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804) first saw them might run like this:

Grasses a few inches high made up the "doormat" of the Rocky Mountains, that is, the strip of land running north and south just east of the mountains. Moving eastward, the plains sloped into the central lowlands where moister winds intruded. Here, the central prairie was the midgrass prairie, the most extensive part of the prairie where the grasses grew to a height of 4 feet. The last zone, farthest to the east, was the tallgrass prairie. Here grasses could grow 8–12 feet tall. The tallgrass prairie spread up to the north as far as Alberta, Canada and west to the Mississippi River. On the eastern edge of the tallgrass prairie—where the plains meet the eastern woodlands—grasses once reached 12 feet tall.

Reaching the plains after Lewis and Clark, the first American settlers known as "homesteaders" promptly plowed them up and planted crops. This pattern continued across the plains, and by 1900, there were barely any examples of prairie land left. Only remnants of the vast tallgrass prairie were still intact, scattered here and there in parks and refuges. Homesteaders on the tallgrass prairie found the sod so dense that it broke their plows. In the plains farther west, they found shortgrass prairie and a more arid environment with better sod, which was their only building material. White settlement disrupted the ecosystem and caused original plants and animals of the plains to die off in great numbers. The great reduction of native plants quickly contributed to soil erosion and created the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

Before white settlers impacted the landscape, native animal species worked together to prevent soil erosion and keep the prairie grassy. Prairie dogs, pocket gophers, and other burrowing animals shaped the landscape and kept the plains grassy for thousands of years. Digging far deeper than any plow, these rodents aerated the soil by loosening the dirt already foraged and trampled by bison, mixing top layers with subsoil, and giving water a way to percolate downward. As a result, the grasses regenerated. It is estimated that as many as 25 billion prairie dogs once inhabited the plains. One colony of 400 million observed in Texas in 1900 covered more than 25,000 square miles. After white settlement reached the plains, domestic cattle overgrazed the grasses. Ironically, ranchers believed the loss of the grasses was due to the prairie dogs, and began slaughtering them in unbelievable numbers. However, the prairie dogs were the true heroes of the successful formation of prairies.

The Great Plains are still there today, but they are devoid of the prairie grasses that made them distinctive to their first European visitors and special to their first human occupants. In fact, the prairie ecosystem is probably the only ecosystem that we cannot see as it looked when Lewis and Clark saw it. The mountains are still there, the woodlands, the deserts, the rainforests, the ocean beaches, but the prairies are gone. The alteration of the prairie illustrates the perils of American expansion. Native American occupation existed for tens of thousands of years, but within two centuries of white settlement, the Great Plains have diminished. Once a hallmark of America's physical landscape, the prairie now serves as a reminder of the importance of preserving the balance of ecosystems.

Question

Which of the following statements best describes the homesteaders' impact on the Great Plains?

| A. Homesteaders' farming and settlement led to soil erosion and created conditions for the Dust Bowl. | ||

| B. Homesteaders ensured the soil stayed aerated in the absence of native plants by plowing. | ||

| C. Homesteaders mapped three zones of the Great Plains, which included the doormat, midgrass, and tallgrass prairies. | ||

| D. Homesteaders settled only in the western plains where sod could be used for building material. |

Explanation

Paragraph 3: Reaching the plains after Lewis and Clark, the first American settlers known as "homesteaders" promptly plowed them up and planted crops. White settlement disrupted the ecosystem and caused original plants and animals of the plains to die off in great numbers. The great reduction of native plants quickly contributed greatly to soil erosion and created the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

To answer the question, you must identify which statement best describes the "homesteaders' impact on the Great Plains." Read the answer choices closely and determine which one best paraphrases (rewords) the information found in the passage.

Scan the passage to locate where the author discusses the homesteaders and how they impacted the prairie. The homesteaders (also referred to as the "white settlement") are first mentioned in P3, which describes how they affected the Great Plains:

The "white settlement disrupted the ecosystem."

They "caused original plants and animals of the plains to die off in great numbers."

Homesteaders caused the "reduction of native plants."

This reduction led to "soil erosion and created the Dust Bowl of the 1930s."

The homesteaders' impact on the Great Plains can best be described in this statement: "Homesteaders' farming and settlement led to soil erosion and created conditions for the Dust Bowl."

(Choice B) The burrowing of prairie dogs kept the soil aerated, not the plowing of the homesteaders.

(Choice C) The Lewis and Clark Expedition, not the homesteaders, mapped the three zones of the Great Plains.

(Choice D) The homesteaders settled all over the prairie, not just the western plains.

Things to remember:

To determine the statement that best describes something or someone in the question, look in the text for the most accurate paraphrase of the question's subject.

Passage

This work is adapted from the article "Elizabeth Bisland's Race around the World" by Matthew Goodman (©2013 by Matthew Goodman).

On the morning of November 14, 1889, John Brisben Walker, the wealthy publisher of the monthly magazine The Cosmopolitan, boarded a New Jersey ferry boat bound for New York City. Like many other New Yorkers, he was carrying a copy of The World, the most widely read and influential newspaper of its time. A front-page story announced that Nellie Bly, The World's star investigative reporter, was about to undertake the most sensational adventure of her career: an attempt to go around the world faster than anyone ever had before. Sixteen years earlier, Jules Verne, in his popular novel, had imagined that such a trip could be accomplished in 80 days; Nellie Bly hoped to do it in 75.

Immediately, Walker recognized the publicity value of such a scheme, and at once an idea suggested itself: The Cosmopolitan would sponsor its own competitor in the around-the-world race, traveling in the opposite direction. Of course, the magazine's circumnavigator would have to leave immediately and would have to be, like Bly, a young woman—the public, after all, would never warm to the idea of a man racing against a woman. But who should it be? Arriving at the offices of The Cosmopolitan that morning, Walker sent a message to the home of Elizabeth Bisland, the magazine's literary editor. It was urgent, he indicated; she should come at once.

Elizabeth Bisland was 28 years old. She was tall; she had large, dark eyes and luminous, pale skin; and she spoke in a low, gentle voice. She reveled in gracious hospitality and smart conversation, both of which were regularly on display in her small apartment, where members of New York's creative set gathered to discuss the artistic issues of the day. Bisland's combination of beauty, charm, and education seems to have been nothing short of bewitching.

Bisland herself was well aware that feminine beauty was useful but fleeting, and she took pride in the fact that she had arrived in New York with only 50 dollars in her pocket and, capable of working for 18 hours at a stretch, she wrote book reviews, essays, feature articles, and classical poetry to build her savings account. She was a believer in the joys of literature, which she had first experienced as a girl in ancient, tattered volumes of Shakespeare and Cervantes that she found in the ruined library of her family's plantation house. She had taught herself French while she churned butter so that she might read Rousseau's Confessions. She cared nothing for fame and indeed found the prospect of it distasteful. So, when she arrived at the offices of The Cosmopolitan and John Brisben Walker proposed that she race Nellie Bly around the world, Elizabeth Bisland refused.

Walker, who had already made fortunes in alfalfa and iron and was in the process of making another in magazine publishing, was not easily dissuaded, and six hours after their carefully measured verbal waltz, Bisland found herself on a New York Central Line train bound for San Francisco. It is important to note that Bisland always described her undertaking for The Cosmopolitan as a "trip" or a "journey," and never as a "race." Still, she was a loyal employee and she threw herself into the competition with vigor. Near the end of the trip, cold and sleepless and hungry, Bisland hurtled by train and ferry through France, England, Wales, and Ireland to catch the steamship that was her last chance to beat Bly. However, she was told the ship had left and was forced to take a slower moving ship across a storm-tossed North Atlantic in the worst weather that had been seen in many years. Despite the rough return home, Bisland, who had never left the country before this trip, discovered a love of travel that would remain for the rest of her life. It provided the vividness of a new world, where one was, for the first time, as Tennyson had written, lord of the five senses. "It was well," she told a friend when it was all over, "to have thus once really lived."

Elizabeth Bisland succeeded in beating Verne's 80-day mark, completing the trip in 76 days—which would have been the fastest but for the fact that Nellie Bly had arrived four days earlier. Bisland arrived home—as she had feared—famous. The race was closely covered by newspapers across the United States, and heavy wagering on the outcome was reported in the country's gambling houses. Bly, whose employer secured her victory by chartering a private train to carry her home, decided, upon her return to New York, to immediately set out on a 40-city lecture tour based on the telegram reports she had sent throughout her journey. Unlike Bly, Bisland did all she could to avoid the glare of publicity, despite her series of articles being published later as a book: In Seven Stages: A Flying Trip Around the World. She gave no lectures, endorsed no products, and did not comment publicly on the trip. In fact, when the American public's interest in her was at its height, Bisland left the United States for Britain where she was romantically pursued by Rudyard Kipling. He wrote to her: "I guess you have enough men under your nose…all the same and until you go after something else new, I am grateful for your attention." A few years later, Bisland returned to the United States, married, and continued writing until the end of her life. She died on January 6, 1929, at the age of 67; her obituary in the New York Times didn't even mention the journey. Today, all of Elizabeth Bisland's books are out of print and she has sadly faded into history along with Nellie Bly.

Question

According to the passage, the delay that caused Bisland to miss the steamship home allowed Bly to:

| A. publish her works before Bisland, thus securing her own celebrity. | ||

| B. endorse several products before Bisland, which ensured her future fortune. | ||

| C. arrive home several days faster, thus famously winning the race. | ||

| D. set out on a lecture tour before Bisland and her employer could plan her own tour. |

Explanation

Paragraphs 5–6: Bisland hurtled by train and ferry through France, England, Wales, and Ireland to catch the steamship that was her last chance to beat Bly. However, she was told the ship had left and was forced to take a slower moving ship…

Elizabeth Bisland succeeded in beating Verne's 80-day mark, completing the trip in 76 days—which would have been the fastest but for the fact that Nellie Bly had arrived four days earlier.

To determine the effect of an event according to the passage, locate its cause (Bisland's missing the steamship home) and skim the surrounding lines to identify the effect.

P5 discusses Bisland's delay after her "ship had left," which required her to "take a slower moving ship." P6 states that this resulted in Bly arriving home "four days earlier" than Bisland. Therefore, the delay caused by Bisland's missing the steamship home allowed Bly to arrive home several days faster, thus famously winning the race.

(Choice A) The passage indicates that both women published reports while participating in the journey and, therefore, does not provide evidence that Bisland's delay allowed Bly to publish her works first.

(Choices B & D) The passage indicates that Bisland "gave no lectures [and] endorsed no products"; Bly was the only one to do these things, not just the first.

Things to remember:

Locate the cause of an event and read the surrounding lines to determine the cause according to the passage.

Humanities Passages

These cover art, literature, music, philosophy, and ethics. Passages may include critiques, discussions on aesthetics, or philosophical debates.

Strategies to Ace Humanities Questions

Here are a few tips to successfully understand humanities passages:

-

Practice interpreting quotes and excerpts

Understand literary and philosophical references in the context of the passage.

-

Draw connections to contemporary issues

Relate themes to present-day ideas and social debates.

-

Explore philosophical and ethical implications

Identify and analyze moral or existential themes raised in the text.

Humanities Questions Examples

Passage

This work is adapted from the article "Peeking Out from Behind da Vinci's Shadow" by Christine Ryan (published by UWorld).

Eyes focused on the sidewalk, people often observe other people's shadows and how they interact with one another. What happens when you move closer together? Further apart? How do the shadows change as the Earth's rotation changes the sun's position in the sky? Sometimes, one shadow's magnitude is so great that it swallows up the surrounding shadows so that one cannot tell each apart.

Most vague shadows eventually become more distinct and clearly defined as we look at them more closely, like the lasting impressions of Michelangelo, Botticelli, and el Greco's Renaissance paintings. But what of the shadows that are swallowed up by another's magnitude? Such is the relationship between da Vinci and his pupil Francesco Melzi. Melzi was born around 1491, approximately 40 years after the man who would become his artistic mentor. Melzi was born into Milanese nobility in Lombardy, Italy, and his superior education included prominent training in the arts. He became da Vinci's favorite pupil and, although little was written about him, he was fairly well known among da Vinci's circle of friends.

While the two were both alive, Melzi was known to be da Vinci's favorite pupil because of his intelligence and talent as a painter. After da Vinci's death, he became lesser known, despite his dedication to collecting, organizing, and preserving many of da Vinci's notes on painting and later turning them into a manuscript known as the Codex Urbinas. He also executed da Vinci's will and cared for his former master's works, which he yearned to share with the world. He rejoiced in bolstering da Vinci's name in the annals of time and was content to remain part of da Vinci's shadow.

Unlike other da Vinci pupils, Melzi's works included a number of museum-quality paintings and drawings, including the famous red chalk on paper portrait of da Vinci's profile. Created in 1515, this work was celebrated for depicting da Vinci as classically handsome, even regal. Melzi also completed other famous red chalk drawings, including Head of an Old Man, Vertumnus and Pomona, Five Grotesque Heads, and Seven Caricatures. However, Melzi wasn't known solely for such chalk drawings; several of his paintings still hang in famous museums today. Among his paintings, the Vertumnus and Pomona—displayed in the Berlin Museum—and Columbina—hanging in the Leningrad Hermitage—were originally attributed to da Vinci, along with several others, reflecting Melzi's true artistic skill. Although he is still not widely recognized, Melzi's name is becoming more recognizable in some art circles due to a recent discovery.

Many people have seen copies or renderings of da Vinci's masterpiece, the Mona Lisa. However, many do not realize that its sister painting currently hangs in Madrid's Museo del Prado. In recent years, during restoration work, conservators studied the painting using X-ray machines to better understand its background and authenticate its creator. What they found excited them: there was increasing evidence that da Vinci's star student painted the work around the same time as da Vinci created the original. They even found that Melzi's changes to the painting coincided with those made by his mentor, contributing to increasing evidence that the two painted these sister masterpieces in close proximity.

However, when studying the restored portrait by Melzi, there are a few distinctions. First, his style isn't as severe as da Vinci's; his version is often noted to be brighter, more colorful, happier. In Melzi's rendering, Mona Lisa's smile is a little bigger, more mysterious; her eyes call out to the audience a little more energetically. Many Renaissance art scholars feel that, while less popular than da Vinci's, Melzi's take is more flattering, albeit less complete, than da Vinci's. In addition, not just because of where it is displayed, but because of the small, stylistic changes, those scholars feel it's better able to escape the shadows, proving more accessible to art fans.

Standing among the Renaissance paintings in the Museo del Prado, all eyes are on Melzi's Mona Lisa. The atmosphere is less hushed than that of the secured original at the Louvre. Patrons appreciate the cheerier space and tone of Melzi's work. This brighter version is awe- and conversation-inspiring. Museum patrons compare it to the more somber original, remarking on each detail. One examines the faint Tuscan landscape in the background while another points out the detail of the chair in which she sits. A docent comments on the decorated dress neckline and more sculpted eyebrows lacking in the original and the patrons lean in to see it. Now that the truth has been unearthed, Melzi's place as part of da Vinci's shadow, part of his lasting contribution toward art, will endure alongside his mentor's.

Question

According to the passage, Melzi appealed to the museum patrons because:

| A.his artwork was happy and vivid. | ||

| B. his artwork used media popular during his time. | ||

| C. he was a well-traveled and talented painter. | ||

| D. he spent time in da Vinci's circle of friends. |

Explanation

P7: Patrons appreciate the cheerier space and tone of Melzi's work. This brighter version is awe- and conversation-inspiring.

When asked to find an answer according to the passage, locate the discussion of why Melzi appealed to museum patrons and skim for details that restate one of the answers.

P7 states that "Patrons appreciate" Melzi's version because it has a "cheerier" tone and is "brighter," thus inspiring conversation. In other words, according to the passage, Melzi appealed to the museum patrons because his artwork was happy and vivid.

(Choice B) The passage does not discuss whether the media Melzi used for his artwork was popular during his time.

(Choice C) Although P3 mentions Melzi's "talent as a painter," it does not discuss whether he was well traveled, nor does it connect his talent as a painter to museum patrons' appreciation of his art.

(Choice D) P2 states that Melzi was "fairly well known among da Vinci's circle of friends," but does not connect this to why museum patrons appreciated his art.

Things to remember:

Locate the subject, compare the details with the answers, and select one that is supported when asked to determine an answer according to the passage.

Passage

This work is adapted from the article "Kraftwerk: The Pioneers of Electropop" by Thomas Winkler (2019 by the Goethe Institute).

Sometimes the present suddenly catches up with the past, as in 2018, when Kraftwerk won the first Grammy in its long history. Not that the world's premiere music prize hadn't already honored the pioneers of electropop. Kraftwerk was recognized for their life's work in 2014 and the Düsseldorf-based group's legendary fourth album Autobahn was ushered into the Grammy Hall of Fame just one year later. Still, it would be half a century from when Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider met and founded Kraftwerk in 1968 before the band won an actual Grammy. The Grammy jury named 3-D The Catalogue the Best Dance/Electronic album of 2018. Kraftwerk prevailed over rivals like Bonobo and Mura Masa, who hadn't even been born when the boys from Düsseldorf were already making history.

Hütter, born in 1946, his changing lineup of musical collaborators, and their recordings in the legendary Kling Klang studio have certainly made both history and waves over the years. Kraftwerk is undoubtedly Germany's most important contribution to pop music. Ground-breaking pop music critic, musician, record label founder, and professed Kraftwerk fan Paul Morley has called them "more important, more beautiful, and more influential than the Beatles ever were."

Some people may be put off by that statement, as the Beatles were far and away the more commercially successful band. But the assertion that Kraftwerk had a greater influence on the evolution of music is not without merit. While the Beatles' music was influenced by earlier pioneers like Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, and Carl Perkins, Kraftwerk materialized out of thin air. The band members are considered the godfathers of techno, and their electronic beats have influenced other genres. Unlike many pop bands of their generation, Kraftwerk incorporated synthesizers and other electronic devices into its music, inspiring and influencing musicians and bands like Tangerine Dream, Depeche Mode, David Bowie, New Order, and Rammstein. When other bands were afraid of technology, Kraftwerk embraced it wholeheartedly. And when rap began picking up speed in the early eighties, New York hip-hop pioneer Africa Bambaataa was not the only one mining Kraftwerk's songs for beats to incorporate into his tracks. A few years later in Detroit, resourceful DJs extracted machinelike rhythms from Kraftwerk's recordings. Today, the international charts are dominated by techno, rap, and many subgenres; those modern innovators never tire of praising Kraftwerk's pioneering achievements. Even the mainstream rock band Coldplay outed themselves as Kraftwerk admirers a few years ago when they used a riff from Kraftwerk's hit Computerlie as the central motif of their hit Talk.

Kraftwerk has long since ceased to be a musical trendsetter, but it has become an institution; new recordings are rare, but the legacy is managed systematically and competently. With dedication and a great deal of secrecy, Hütter toils away on his own mythology. There are very few interviews, no details from his private life, and only a few carefully staged photos, no collaborations—not even with Michael Jackson, who is said to have expressed interest in collaborating at the height of his fame in the eighties. At the time, Kraftwerk was conducting research on the interface between human existence and modern technology. Visuals, staging and philosophy were just as important as the music, and referencing conceptual art was part of the program. Just the fact that the band incorporated ideas and methods from Dadaism, Constructivism, and Bauhaus would ultimately secure Kraftwerk a place in art history.

Consequently, Kraftwerk increasingly prefers performing at art festivals like the Ars Electronica in Linz (1993) or in museums like the New York Museum of Modern Art (2012) or the Berlin New National Gallery (2015). In the past five years, the band has performed one hundred and twenty-five concerts in thirty countries, primarily in such artistic venues. The concept of Kraftwerk is best expressed in art spaces, and its technological developments have begun to realize the metamorphosis from man to machine that was merely a dream when the band first formed. In the early days, the machinelike beats still emanated from drums and the members performed organ, flute, and violin improvisations. Today, Kraftwerk primarily sends out manikin and robot representatives to produce its electronic music. Hütter recently commented on the band's evolution: "We've just never really taken a look [back] at [our early] albums. Now we incorporate more artwork, so Emil has researched contemporary drawings, graphics, and photographs to go with each re-released album, collections of paintings that we worked with, and drawings that Florian and I did. We took a lot of Polaroids in the early days, which we want to include." These plans, along with their new iOS app (Kraftwerk Kling Klang Machine), just emphasize that the people behind Kraftwerk have long since been eclipsed by their visual and auditory art, yet this helped them keep with the times more than ever.

1. This work, "Kraftwerk," is a derivative of "Kraftwerk: The Pioneers of Electropop" by Thomas Winkler, published by the Goethe Institute under CC BY-SA 3.0. "Kraftwerk" is licensed under CC BY-SA by UWorld.

Question

The passage states that which of the following sets the members of Kraftwerk apart from their contemporaries?

| A.They turned to Elvis Presley for inspiration while their peers turned to Chuck Berry. | ||

| B. They preferred performing music to recording and composing it. | ||

| C. They completely welcomed technology rather than fearing it. | ||

| D. They considered live drums to be an integral part of their performances. |

Explanation

Paragraph 3: When other bands were afraid of technology, they embraced it wholeheartedly.

When asked what the passage states, locate the subject matter (what approach to music sets the members of Kraftwerk apart from their contemporaries), note the details, and select the supported answer.

P3 states that "when other bands" (their contemporaries) feared technology, Kraftwerk "embraced it wholeheartedly" (completely). In other words, the members of Kraftwerk were set apart from their contemporaries because they completely welcomed technology rather than fearing it.

(Choice A) P3 states that the Beatles were influenced by pioneers including Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry, whereas Kraftwerk was not.

(Choice B) The band members have recently been replaced by manikins and robots, which is in opposition to preferring performing to recording and composing.

(Choice D) P5 states that Kraftwerk's use of drums has been replaced by electronic drumbeats—the opposite of this choice.

Things to remember:

Locate the subject, note the details, and select the supported answer when asked to determine what the passage states.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many passages are there in the ACT Reading section and what are their types?

There are 4 types of passages in the ACT Reading section:

- Literary Narrative and Prose Fiction

- Natural Science

- Social Studies

- Humanities

What approach is most effective for tackling the ACT Reading section?

Refer back to the passages. The Reading section evaluates your reading and comprehension skills, not your general knowledge. So, it’s crucial to base all your answers on the evidence presented in the passages.

What are the most common mistakes to avoid when answering ACT Reading questions?

The most common mistakes that students make while taking the ACT Reading test are:

- Not reading passages and questions carefully

- Basing answers on personal opinion

- Misinterpreting questions

- Not managing time effectively

Now that you know everything about different ACT Reading question types, it’s time to start practicing using our ACT Assessment Test. Also, make sure to read our blog on Common ACT Reading Mistakes, which shares more about how to avoid them and score well on your test.

Read More Related Articles

Unsure of how to start your ACT Reading prep? Explore our guide to find valuable tips and strategies for approaching the Reading section and aim for a flawless score of 36.

ACT Math Study Plan & TipsReady to kick-start your ACT Math prep but feeling overwhelmed? This article provides multiple tips and strategies to help you conquer the Math section with confidence.

ACT English Study Plan & TipsAre you thinking of preparing for your ACT English test? Use our comprehensive guide with proven tips and techniques to get your desired score on the English section.

ACT Science Study Plan & TipsEmbarking on your ACT Science prep journey? Prepare the right way! Here is a guidebook to help you prepare efficiently for your Science test and get your dream score.