What Geometry Is on the SAT?

Most SAT® geometry questions fall into a few predictable buckets:

- Lines and angles (vertical angles, linear pairs, parallel lines with transversals)

- Triangles (triangle inequality, special right triangles, similarity, basic trig)

- Circles (radii, chords, arcs, inscribed angles, tangents)

- Area, perimeter, and volume (often in word-problem form)

- Coordinate geometry (distance, midpoint, slope, equations of lines and circles)

Mastering these shapes is essential, but they are just one piece of the puzzle. To build a complete study plan, you should verify how these geometry rules balance against the other major topics in the SAT Math section.

SAT Geometry Skills You’ll Apply Most Often

SAT Geometry is rarely about doing long proofs. Most SAT Geometry questions reward repeatable moves: identify the relationship, label the figure, and translate what you see into an equation. When these skills start clicking, geometry questions on SAT become much easier to spot and solve, especially alongside the broader topic expectations in the SAT Math section. When you’re ready to apply these skills, targeted SAT practice questions make it easier to drill angles, triangles, circles, and coordinate geometry in realistic formats.

Use Angle-Relationships to Unlock the Diagram

Angle problems often look diagram-heavy, but they usually boil down to a few SAT Geometry rules. Start by marking any parallel lines, right angles, or intersecting lines, then hunt for relationships you can use immediately.

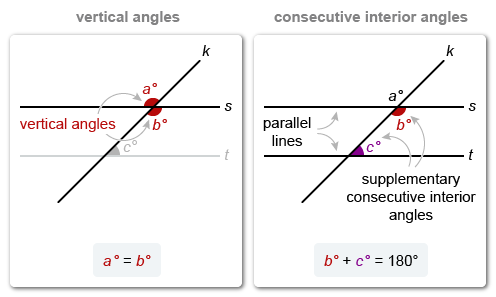

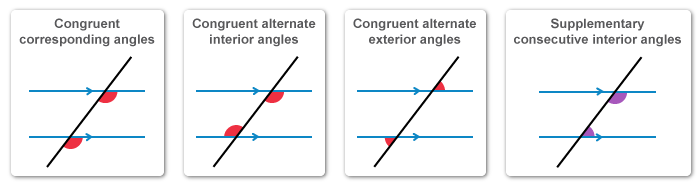

The angle relationships that show up most in geometry for the SAT include:

- Vertical angles are equal.

- Linear pairs add to 180°.

- Angles around a point add to 360°.

- With parallel lines, corresponding angles are equal, alternate interior angles are equal, and same-side interior angles add to 180°.

When time is tight, strategies like plugging in answers can help you test angle relationships without doing extra algebra.

Use Similarity and Proportional Reasoning in Triangles

Triangle problems often become straightforward once you identify similar triangles and set up proportions. Similarity commonly appears when a segment is drawn parallel to a triangle side or when two triangles share an angle and have a second matching angle.

Note: When the geometry turns into algebra, apply the same steady equation-solving habits you use on the rest of the test to prevent mix-ups.

Connect circles to angles, arcs, and tangents

Circle geometry SAT questions can feel tricky if you rely on the picture, but they’re manageable when you remember how angles and arcs connect.

High-value circle relationships include:

- A central angle matches the measure of its intercepted arc (in degrees).

- An inscribed angle equals half the measure of its intercepted arc.

- A tangent is perpendicular to the radius at the point of tangency.

When you see arc markings or an angle on the circle, label the intercepted arc right away. Many SAT circle geometry problems are really testing whether you can match the angle to the correct arc and apply the correct “half” relationship.

Apply Area and Volume Formulas in Context

SAT Geometry formulas are important, but the SAT usually tests whether you can apply them in real situations, not whether you can recite them. A lot of mistakes happen when students plug into a formula too early without confirming what the diagram or wording actually represents.

To stay accurate:

- Identify what the question is truly asking for (area vs perimeter, surface area vs volume).

- Track units carefully (square units for area, cubic units for volume).

- Look for scaling language. If lengths scale by a factor of k, areas scale by k2, and volumes scale by k3.

When you practice, it helps to keep a consistent set of geometry formulas handy, so you build automatic recall and faster execution. A focused SAT study guide can also help you review the most-used geometry formulas and see quick examples of when each one applies.

Use Coordinate Tools (Slope, Distance, Midpoint) When Figures Are on a Grid

Coordinate geometry SAT questions often look like geometry, but they behave like algebra. When points, lines, or shapes are placed on a grid, your fastest tools are usually:

- Slope to prove lines are parallel or perpendicular

- Distance to prove sides are equal or to find side lengths

- Midpoint to find symmetry or bisected segments

A reliable approach:

- Copy down the coordinates and label the points.

- Decide what the problem is really testing: alignment (slope), length (distance), or halfway structure (midpoint).

- Use the cleanest tool, then simplify.

This is also where students can save time by avoiding messy diagram reasoning. Coordinate geometry is often the shortcut that turns hard SAT Geometry questions into quick arithmetic.

How to Read and Break Down SAT Geometry Diagrams

SAT Geometry diagrams are less about memorizing formulas and more about applying the right geometry rules at the right moment. If you are struggling to get started, the solution is usually found in your diagram-reading habits, not in rote memorization. Strong diagram habits help you spot the givens, avoid wrong assumptions, and build the exact equation the problem is testing, which is the real goal of most geometry rules for SAT questions.

When the Diagram Is NOT to Scale

Unless a question specifically states that a figure is drawn to scale, assume it isn’t. Never trust the visual appearance of a diagram over the actual numbers and labels.

Rely only on what is stated or marked:

- Equal lengths must be shown with tick marks or stated in text.

- Equal angles must be shown with matching arcs or stated in text.

- Parallel lines must be marked with arrows or stated.

- Right angles must have a square corner mark or be stated.

Common trap: A triangle may look isosceles or an angle may look like 90°, but unless it’s marked, it’s not a usable fact. Treating visuals like evidence is one of the fastest ways to miss SAT Geometry questions.

When You Should Redraw the Diagram

Redrawing is a speed tool, not extra work. Redraw when the original diagram makes it easy to misread relationships or hard to label information clearly.

Redraw if:

- The figure is tilted or stretched, making angles and sides visually misleading.

- Labels are crowded or far from the segments they describe.

- The diagram includes multiple shapes (a triangle inside a circle, composite figures).

- You need a clean coordinate plane to track points and distances.

How to redraw efficiently:

- Copy only what matters: tick marks, angle arcs, parallel arrows, right-angle boxes.

- Keep your redraw simple and leave space for algebra or ratio notes.

- Re-label points in the same order so your work stays consistent with the question.

Mark Up Every Given Relationship

Before you solve anything, mark up the diagram so the key relationships are visible. This step prevents phantom facts and makes geometry rules easier to apply correctly.

Mark these immediately:

- Parallel lines (arrows), then look for corresponding or alternate interior angles.

- Perpendicular lines (90°), then check for complementary angles and right triangles.

- Congruent sides (tick marks), which often signal isosceles triangles or equal segments.

- Congruent angles (arcs) often signals triangle similarity or angle chasing.

- Midpoints or bisectors which usually create equal parts or proportional segments.

- Circle relationships (radius, tangent point), especially the radius-to-tangent 90° rule.

Quick self-check: If a relationship is not marked or stated, don’t use it. That one rule eliminates a big chunk of avoidable errors.

Convert Words → Sketch → Equation

Many SAT Geometry problems are really word problems with geometric clothing. To solve them efficiently, use a consistent translation process:

- Words → sketch: draw the simplest version of the situation (not a “pretty” picture).

- Sketch → labels: add every given value with units and define your variable clearly.

- Labels → equation: choose the relationship that matches the situation (angle sum, similarity ratios, area/volume setup, distance formula).

Habits that prevent common mistakes:

- Underline what’s asked. Students often solve for radius when the question wants diameter, or solve for area when it wants perimeter.

- Translate comparisons carefully. Phrases like “twice as long,” “increases by 20%,” or “x more than” should become explicit expressions before you plug anything in.

By anchoring your work in the given information, you avoid common pitfalls and ensure every equation you set up is accurate

Strategies to Solve SAT Geometry Questions Faster

To get faster at SAT Geometry, focus on decisions that shorten the path to the answer: extract the right relationships, avoid unnecessary calculations, and use the diagram the way the test expects. Additionally, a comprehensive SAT prep course reinforces these habits, helping you recognize exactly which shortcuts to take under pressure.

- Treat the diagram like a list of facts, not a picture. Stick strictly to relationships that are physically marked or written in the text. Unless you see specific notation, like tick marks or arrows, you cannot treat a visual appearance as a mathematical fact.

- Hunt for the one relationship that unlocks the problem. Most SAT Geometry questions hinge on one key move, like an angle relationship from parallel lines, a similarity ratio in triangles, or an inscribed-angle rule in circles. Once you find it, write one equation and commit.

- Label what you need, then stop. Add the minimum number of labels to create a solvable equation. Over-labeling leads to extra steps and increases the chance of arithmetic slips.

- Use coordinates as a shortcut when you can. On grid-based problems, slope, distance, and midpoint are often faster than traditional geometry reasoning, especially when you need to prove lines are parallel or find a missing length.

- Exploit answer choices strategically. If choices are widely spaced, a quick estimate can eliminate options immediately. If choices are close, solve only to the point where one option clearly matches your result.

- Avoid the classic “wrong target” trap. Geometry questions often make you solve for an intermediate value (like radius) when the question asks for something else (like diameter or circumference). Circle what the question is asking for before you select an answer.

- Stay precise on grid-ins. Even with the right value, you can lose points if you enter it incorrectly, so keep grid-in format rules in mind when the answer is a fraction or decimal.

Hard Geometry Problems: How the SAT Tries to Trick You

Hard SAT Geometry problems usually aren’t hard because the concepts are advanced. They’re hard because the test sets traps that reward careful reading, clean diagram logic, and accurate use of geometry rules for the SAT.

- The diagram may look like it shows equal sides, right angles, or symmetry, but unless it’s marked or stated, it isn’t a usable fact in SAT Geometry questions.

- Keywords like parallel, midpoint, bisects, and tangent often contain the shortcut, so missing them can make hard SAT Geometry questions feel much longer than they need to be.

- If your solution is turning into a long chain of steps, you likely missed a faster relationship like similar triangles, a circle angle rule, or a coordinate shortcut.

- The test often pushes you to solve an intermediate value (like radius or a partial length) when the question asks for something else (diameter, total length, perimeter, or 2).

- Many hard SAT Geometry problems become algebra-heavy once the relationship is set up, especially when side lengths are written as expressions or ratios.

- Relying on visual assumptions is a frequent trap. It is always safer to trust the explicit markings and stated relationships than to guess based on how the diagram is drawn.

Sample SAT Geometry Questions (With Solutions)

The fastest way to improve in SAT Geometry is to practice with realistic, test-style prompts that mirror how SAT Geometry questions are written. As you work through these SAT Geometry practice questions, focus on the relationship each problem is testing (angles, similarity, circles, coordinate geometry, or area and volume), then review your setup to confirm you applied the right geometry rules before checking the final answer.

Question

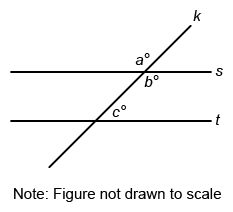

In the figure, lines s and t are parallel and line k intersects both lines. If a = 5n + 16 and b = 7n − 32, what is the value of c ?

| A. 4 | |

| B. 24 | |

| C. 44 | |

| D. 136 |

When two lines intersect, they form pairs of vertical angles that are equal in measure.

Explanation

When two lines intersect, they form pairs of vertical angles that are equal in measure. Therefore, the angles marked a° and b° are equal in measure.

Notice that the angles marked b° and c° are on the same side of transversal k and that they are between parallel lines s and t, so they are consecutive interior angles and must be supplementary (sum to 180°).

Use the given expressions for a and b to first solve for n, and then find the value of b. Use the value of b to then find the value of c.

It is given that a = 5n + 16 and b = 7n – 32, so set the expressions equal and solve for n.

| 5n + 16 = 7n − 32 | Set expressions of a and b equal |

| 16 = 2n − 32 | Subtract 5n from both sides |

| 48 = 2n | Add 32 to both sides |

| 24 = n | Divide by 2 on both sides |

The value ofn is 24. Plug n = 24 into the equation that relates b and n to find the value of b.

| b = 7n − 32 | Equation for angle b° |

| b = 7(24) − 32 | Plug in n = 24 |

| b = 136 | Simplify |

The angle marked b° is 136°. The angles b° and c° are supplementary, so set the sum of b and c equal to 180 and solve for c.

| b + c = 180 | Angles b and c are supplementary |

| 136 + c = 180 | Plug in b = 136 |

| c = 44 | Subtract 136 from both sides |

The value of c is 44.

(Choice A) 4 may result from the combination of adding 5n to both sides of the equation 5n + 16 = 7n − 32 when attempting to solve for n and the error described in Choice B.

(Choice B) 24 is the value of n, but the question asks for the value of c.

(Choice D) 136 is the value of both a and b, but the question asks for the value of c.

Things to remember:

- When two lines intersect, they form pairs of vertical angles that are equal in measure.

- When parallel lines are intersected by a transversal, the following pairs of angles are formed:

Question

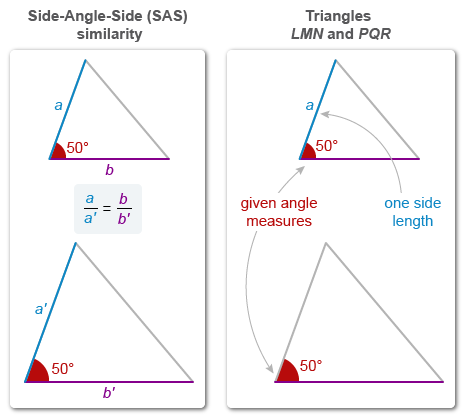

Triangles LMN and PQR each have a corresponding angle measuring 50°. Which additional piece of information is sufficient to determine whether these two triangles are similar?

| A. The measure of another pair of corresponding angles in the two triangles | |

| B. The lengths of one pair of corresponding sides in the two triangles | |

| C. The length of segment LN | |

| D. The length of segment PQ |

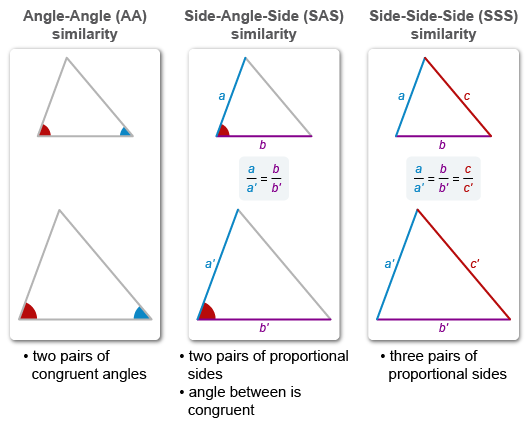

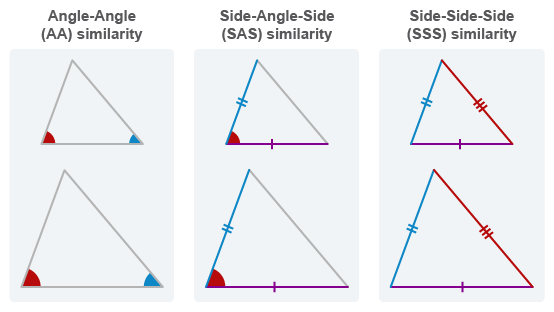

The three triangle similarity theorems are Angle-Angle (AA), Side-Angle-Side (SAS), and Side-Side-Side (SSS).

Explanation

Triangle similarity theorems describe combinations of congruent angles and proportional side lengths that are sufficient to prove that triangles are similar.

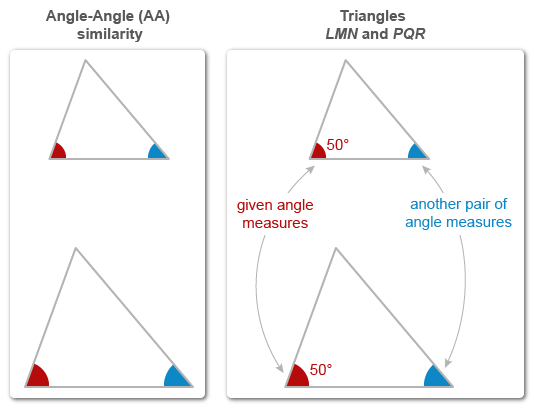

It is given that triangles LMN and PQR each have a corresponding angle measuring 50°, so they have one pair of congruent angles.

Consider each choice along with the triangle similarity theorems to see which piece of additional information is sufficient to determine whether the triangles are similar.

(Choice A) The measure of another pair of corresponding angles in the two triangles

If the measures of two pairs of corresponding angles are congruent, then triangles are similar by Angle-Angle similarity.

Therefore, this information is sufficient to determine whether triangles LMN and PQR are similar.

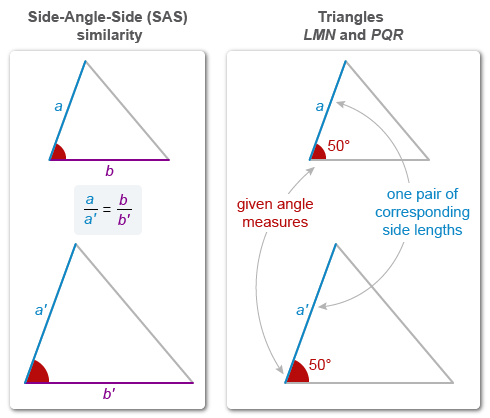

(Choice B) The lengths of one pair of corresponding sides in the two triangles

If congruent angles are between two pairs of proportional sides, then the triangles are similar by Side-Angle-Side similarity.

The lengths of one pair of corresponding sides are not enough information to determine if two pairs of sides are proportional.

Therefore, this information is NOT sufficient to determine whether triangles LMN and PQR are similar.

(Choices C and D) The length of segment and the length of segment

The length of one side of one triangle is not enough information to determine a ratio of sides.

Therefore, this information is NOT sufficient to determine whether triangles LMN and PQR are similar.

Things to remember:

To prove triangle similarity, use one of the three triangle similarity theorems: Angle-Angle (AA), Side-Angle-Side (SAS), and Side-Side-Side (SSS).

Question

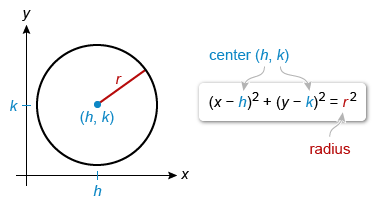

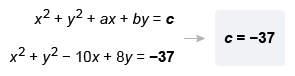

An equation of a circle in the xy-plane with radius 2 and center at (5, −4) is x2 + y2 + ax + by = c. What is the value of c ?

The equation of a circle in standard form is (x − h)2 + (y − k)2 = r 2.

Explanation

Correct Answer: C = -37

The equation of a circle in standard form is (x − h)2 + (y − k)2 = r 2, where (h, k) is the center and r is the length of the radius.

The given circle has radius 2 and center at (5, −4), so plug in r = 2 and (h, k) = (5, −4) to get an equation of the circle in standard form. Then rewrite the equation in the form x2 + y2 + ax + by = c to identify the value of c.

| (x − h)2 + (y − k)2 = r2 | Standard form |

| (x − 5)2 + (y − (−4))2 = 22 | Plug in (h, k) = (5, −4) and r = 2 |

| (x − 5)2 + (y + 4)2 = 4 | Simplify |

Now expand the perfect squares (x − 5)2 and (y + 4)2 and then rearrange the equation to the form x2 + y2 + ax + by = c.

| (x − 5)2 + (y + 4)2 = 4 | |

| x2 − 10x + 25 + y2 + 8y + 16 = 4 | Expand (x − 5)2 and (y + 4)2 |

| x2 + y2 − 10x + 8y + 41 = 4 | Rearrange and combine constant terms on left |

| x2 + y2 − 10x + 8y = −37 | Subtract 41 from both sides |

Compare the resulting equation to the given equation to identify c.

Things to remember:

-

The equation of a circle in standard form is (x − h)2 + (y − k)2 = r 2, where (h, k) is the center and r is the length of the radius.

-

To expand (a + b)2, use the identity (a + b)2 = a2 + 2ab + b2 or rewrite the expression (a + b)2 as (a + b)(a + b) and multiply.

Question

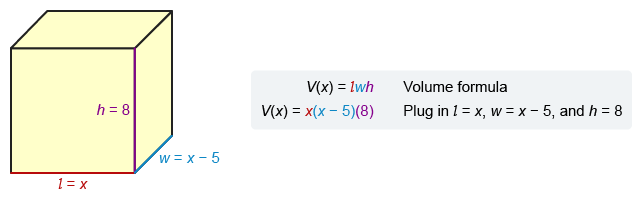

A right rectangular prism has a base with a length of x feet, which is 5 feet more than its width. If the height of the prism is 8 feet, which function V gives the volume of the prism, in cubic feet, in terms of the length of the prism's base?

| A. V(x) = 8x(x − 5) | |

| B. V(x) = 8x(x + 5) | |

| C. V(x) = x(x − 5)(x + 8) | |

| D. V(x) = x(x + 5)(x + 8) |

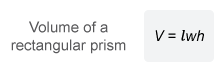

The formula for the volume of a right rectangular prism is , where and are the length and width of the base and is the height.

Explanation

The formula for the volume of a right rectangular prism is , where and are the length and width of the base and is the height. For the given prism, the height is 8 and the base length is x.

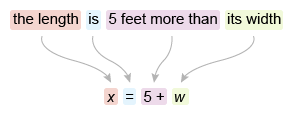

The function notation V(x) means the volume V in terms of x, which is the given length of the prism. To write an equation for V(x), it is necessary to express the width w in terms of the length x.

First use the given information to write an equation for the length x in terms of the width w.

Now solve for w to get an equation for w in terms of x.

| x = 5 + w | Given equation |

| x − 5 = w | Subtract 5 from both sides |

The width w is equal to x − 5.

Plug , , and into the volume formula to write an equation for the function V(x).

To match the answer choices, rearrange to see that the function for the volume of the prism in terms of the length of its base is V(x) = 8x(x − 5).

(Choice B)V(x) = 8x(x + 5) is incorrect because it represents a width that is 5 more than the length (instead of a length that is 5 more than the width).

(Choice C)V(x) = x(x − 5)(x + 8) may result from mistaking the height to be 8 more than the length, but it is given that the height of the prism is equal to 8.

(Choice D)V(x) = x(x + 5)(x + 8) may result from the combination of errors described in Choices B and C.

Things to remember:

The formula for the volume of a right rectangular prism is , where and are the length and width of the base and is the height.

After working through these examples, a timed SAT practice test is a good way to check whether you can recognize the right geometry rules under pressure.

SAT Geometry: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many geometry questions appear on the SAT?

The SAT does not publish an exact, fixed number of geometry questions per test. Instead, geometry concepts appear throughout the Math section alongside algebra and problem-solving. On some tests, you may see more geometry-heavy items, while others may lean more toward linear equations or data analysis. A better approach is to be comfortable with the most common geometry skills, not to aim for a specific count. Expect geometry to show up as both diagram-based questions and real-world word problems. If your goal is consistency, focus on recognizing which geometry relationship a question is testing and setting up the right equation quickly.

Do I need to memorize SAT Geometry formulas if there’s a formula sheet?

You do not need to memorize every formula, but you do need to know how to use formulas quickly and correctly. The bigger challenge is usually recognizing which formula applies and avoiding mix-ups like area vs perimeter or surface area vs volume. Knowing a few high-frequency relationships from memory also saves time, especially when you are working under pressure. A formula reference helps, but it will not tell you which values to plug in or how to translate a word problem into the right setup. If you rely only on a SAT Math formula sheet without understanding, it is easy to choose the wrong formula and get the wrong answer quickly.

Are SAT Geometry questions hard?

Most SAT Geometry questions are designed to be manageable if you know the core relationships and can read diagrams carefully. The hard ones usually feel hard because of traps, not because they use advanced geometry. Common difficulty drivers include not-to-scale diagrams, missing a keyword like “parallel” or “midpoint,” or solving for the wrong quantity. Geometry questions can also become algebra-heavy once you set up the relationship. If you keep your work organized and focus on the simplest path, many hard-looking questions become straightforward.

Are SAT Geometry diagrams drawn to scale?

Usually, you should assume diagrams are not drawn to scale unless the problem explicitly says they are. That means you cannot assume lengths or angles are equal just because they look equal. Only trust what is marked with tick marks, angle arcs, right-angle boxes, or what is stated in the text. This rule prevents a lot of avoidable mistakes in SAT Geometry questions. If something feels obvious from the picture but is not labeled, treat it as a warning sign. The SAT rewards using given information, not visual guessing.

Are there geometry questions where the diagram is misleading on purpose?

Yes, the test may include diagrams that are visually suggestive to see if you will make an unsupported assumption. For example, a triangle may look isosceles even when it is not labeled as such, or an angle may look like 90° without a right-angle mark. This is a common way the SAT increases difficulty without changing the underlying math. The best defense is to slow down for two seconds and confirm what is actually given. If it is not marked or stated, do not use it. Treat the diagram as a guide for relationships, not as proof.

What should I do if the diagram seems to contradict the numbers?

When the picture and the numbers disagree, trust the numbers and the written statements. The diagram may be distorted, rotated, or not to scale, and it is not meant to be used for measuring by sight. Re-read the question for key constraints like parallel lines, midpoints, or tangents that affect the geometry rules you should apply. Redraw a cleaner version of the figure if the original is confusing, and label it using only the given information. Then set up the relationship using equations, not visual estimates. If your setup is correct, the contradiction usually disappears.

What should I do if my answer isn’t in the choices?

First, re-check what the question is actually asking for, because a common mistake is solving for radius instead of diameter, or area instead of perimeter. Next, confirm you did not assume something from the diagram that was not marked or stated. Then review arithmetic and sign errors, especially in coordinate geometry and distance problems. If the answer choices are close together, estimate your result to see which choice your value should be near. If nothing matches, back up to your first equation and confirm it reflects the correct relationship. Most of the time, the issue is a wrong target, a wrong formula, or one missed detail in the setup.