AP® English Literature Tests & Questions

A's and 5's in AP Lit Made Easy

AP English Literature Practice Test Questions for Free

AP English Literature Practice Test: Characterization

Passage: The Awakening by Kate Chopin

Madame Ratignolle laid her hand over that of Mrs. Pontellier, which was near her. Seeing that the hand was not withdrawn, she clasped it firmly and warmly. She even stroked it a little, fondly, with the other hand, murmuring in an undertone, "Pauvre Cherie1."

The action was at first a little confusing to Edna, but she soon lent herself readily to the Creole's2 gentle caress. She was not accustomed to an outward and spoken expression of affection, either in herself or in others. She and her younger sister, Janet, had quarreled a good deal through force of unfortunate habit. Her older sister, Margaret, was matronly and dignified, probably from having assumed matronly and housewifely responsibilities too early in life, their mother having died when they were quite young. Margaret was not effusive; she was practical. Edna had had an occasional girl friend, but whether accidentally or not, they seemed to have been all of one type—the self-contained. She never realized that the reserve of her own character had much, perhaps everything, to do with this. Her most intimate friend at school had been one of rather exceptional intellectual gifts, who wrote fine-sounding essays, which Edna admired and strove to imitate; and with her she talked and glowed over the English classics, and sometimes held religious and political controversies.

Edna often wondered at one propensity which sometimes had inwardly disturbed her without causing any outward show or manifestation on her part. At a very early age—perhaps it was when she traversed the ocean of waving grass—she remembered that she had been passionately enamored of a dignified and sad-eyed cavalry officer who visited her father in Kentucky. She could not leave his presence when he was there, nor remove her eyes from his face, which was something like Napoleon's, with a lock of black hair failing across the forehead. But the cavalry officer melted imperceptibly out of her existence.

At another time her affections were deeply engaged by a young gentleman who visited a lady on a neighboring plantation. It was after they went to Mississippi to live. The young man was engaged to be married to the young lady, and they sometimes called upon Margaret, driving over of afternoons in a buggy. Edna was a little miss, just merging into her teens; and the realization that she herself was nothing, nothing, nothing to the engaged young man was a bitter affliction to her. But he, too, went the way of dreams.

She was a grown young woman when she was overtaken by what she supposed to be the climax of her fate. It was when the face and figure of a great tragedian began to haunt her imagination and stir her senses. The persistence of the infatuation lent it an aspect of genuineness. The hopelessness of it colored it with the lofty tones of a great passion.

The picture of the tragedian stood enframed upon her desk. Any one may possess the portrait of a tragedian without exciting suspicion or comment. (This was a sinister reflection which she cherished.) In the presence of others she expressed admiration for his exalted gifts, as she handed the photograph around and dwelt upon the fidelity of the likeness. When alone she sometimes picked it up and kissed the cold glass passionately.

Her marriage to Leonce Pontellier was purely an accident, in this respect resembling many other marriages which masquerade as the decrees of Fate. It was in the midst of her secret great passion that she met him. He fell in love, as men are in the habit of doing, and pressed his suit with an earnestness and an ardor which left nothing to be desired. He pleased her; his absolute devotion flattered her. She fancied there was a sympathy of thought and taste between them, in which fancy she was mistaken. Add to this the violent opposition of her father and her sister Margaret to her marriage with a Catholic, and we need seek no further for the motives which led her to accept Monsieur Pontellier for her husband.

The acme of bliss, which would have been a marriage with the tragedian, was not for her in this world. As the devoted wife of a man who worshiped her, she felt she would take her place with a certain dignity in the world of reality, closing the portals forever behind her upon the realm of romance and dreams.

But it was not long before the tragedian had gone to join the cavalry officer and the engaged young man and a few others; and Edna found herself face to face with the realities. She grew fond of her husband, realizing with some unaccountable satisfaction that no trace of passion or excessive and fictitious warmth colored her affection, thereby threatening its dissolution.

(1899)

Question

The narrator mentions Madame Ratignolle's behavior in lines 1-3 to emphasize that she is

| A. perplexed | |

| B. nostalgic | |

| C. supportive | |

| D.condescending |

Explanation

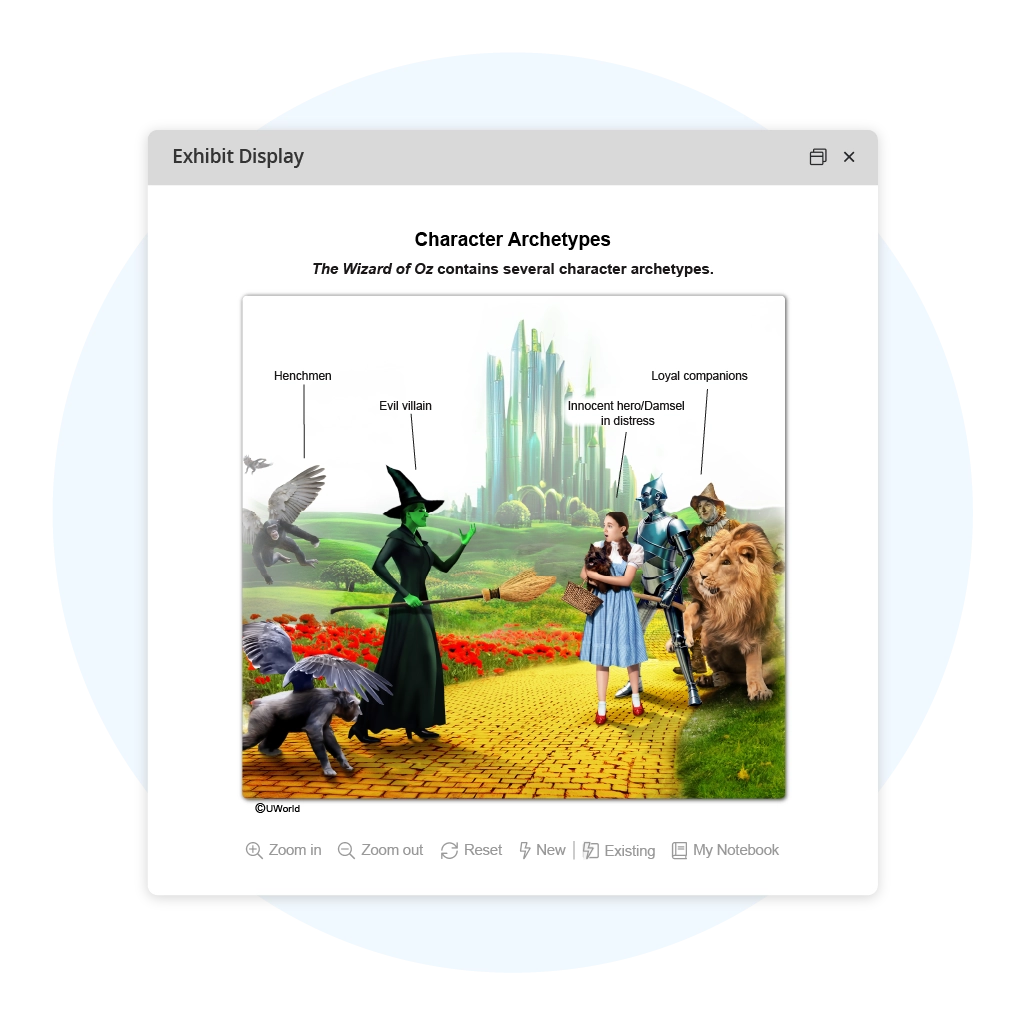

To best describe a character, identify what that person does and says, and then determine what quality is revealed by that information.

In P1, Madame Ratignolle:

- "laid her hand over that of Mrs. Pontellier"

- "clasped it firmly and warmly…fondly"

- "murmur[ed]…"Pauvre Cherie'" ("Poor Darling")

Placing her hand on that of Mrs. Pontellier and whispering the sympathetic comment "Pauvre Cherie" are meant to comfort Mrs. Pontellier. Madame Ratignolle's display of kindness shows that she is caring and concerned for her friend. Although the reader doesn't yet know why Mrs. Pontellier is upset, the reader can infer that the narrator mentions Madame Ratignolle's behavior to emphasize that she is supportive.

(Choice A) After the lines in question, the narrator states that Edna (Mrs. Pontellier), not Madame Ratignolle, was "confused" by the hand clasp.

(Choice B) Someone who is nostalgic reflects fondly on the past; however, in the paragraphs after the lines mentioned, Mrs. Pontellier, not Madame Ratignolle, reflects on her past.

(Choice D) The details in the passage do not suggest that Madame Ratignolle is condescending (showing superiority) to Mrs. Pontellier. Her actions are meant to comfort Mrs. Pontellier.

Things to remember:

Authors include details about characters' words and actions to give the reader insight into their nature.

Passage: "Roman Fever" by Edith Wharton

"I wish now I hadn't told you. I'd no idea you'd feel about it as you do; I thought you'd be amused. It all happened so long ago, as you say; and you must do me the justice to remember that I had no reason to think you'd ever taken it seriously. How could I, when you were married to Horace Ansley two months afterward? As soon as you could get out of bed your mother rushed you off to Florence and married you. People were rather surprised—they wondered at its being done so quickly; but I thought I knew. I had an idea you did it out of pique—to be able to say you'd got ahead of Delphin and me. Kids have such silly reasons for doing the most serious things. And your marrying so soon convinced me that you'd never really cared."

"Yes. I suppose it would," Mrs. Ansley assented.

The clear heaven overhead was emptied of all its gold. Dusk spread over it, abruptly darkening the Seven Hills. Here and there lights began to twinkle through the foliage at their feet. Steps were coming and going on the deserted terrace—waiters looking out of the doorway at the head of the stairs, then reappearing with trays and napkins and flasks of wine. Tables were moved, chairs straightened. A feeble string of electric lights flickered out. A stout lady in a dustcoat suddenly appeared, asking in broken Italian if anyone had seen the elastic band which held together her tattered Baedeker*. She poked with her stick under the table at which she had lunched, the waiters assisting.

The corner where Mrs. Slade and Mrs. Ansley sat was still shadowy and deserted. For a long time neither of them spoke. At length Mrs. Slade began again: "I suppose I did it as a sort of joke—."

"A joke?"

"Well, girls are ferocious sometimes, you know. Girls in love especially. And I remember laughing to myself all that evening at the idea that you were waiting around there in the dark, dodging out of sight, listening for every sound, trying to get in—of course I was upset when I heard you were so ill afterward."

Mrs. Ansley had not moved for a long time. But now she turned slowly toward her companion.

"But I didn't wait. He'd arranged everything. He was there. We were let in at once," she said.

Mrs. Slade sprang up from her leaning position. "Delphin there! They let you in! Ah, now you're lying!" she burst out with violence.

Mrs. Ansley's voice grew clearer, and full of surprise. "But of course he was there. Naturally he came—."

"Came? How did he know he'd find you there? You must be raving!"

Mrs. Ansley hesitated, as though reflecting. "But I answered the letter. I told him I'd be there. So he came."

Mrs. Slade flung her hands up to her face. "Oh, God—you answered! I never thought of your answering...."

"It's odd you never thought of it, if you wrote the letter."

"Yes. I was blind with rage."

Mrs. Ansley rose, and drew her fur scarf about her. "It is cold here. We'd better go.... I'm sorry for you," she said, as she clasped the fur about her throat.

The unexpected words sent a pang through Mrs. Slade. "Yes; we'd better go." She gathered up her bag and cloak. "I don't know why you should be sorry for me," she muttered.

Mrs. Ansley stood looking away from her toward the dusky mass of the Colosseum. "Well— because I didn't have to wait that night."

Mrs. Slade gave an unquiet laugh. "Yes, I was beaten there. But I oughtn't to begrudge it to you, I suppose. At the end of all these years. After all, I had everything; I had him for twenty-five years. And you had nothing but that one letter that he didn't write."

Mrs. Ansley was again silent. At length she took a step toward the door of the terrace, and turned back, facing her companion.

"I had Barbara," she said, and began to move ahead of Mrs. Slade toward the stairway.

1. From ROMAN FEVER AND OTHER STORIES by Edith Wharton. Copyright © 1934 by Liberty Magazine. Copyright renewed © 1962 by William R. Tyler. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Question

Mrs. Slade's comments in the sixth paragraph (lines 19–21) primarily suggest that she

| A. hopes to receive Mrs. Ansley's forgiveness | |

| B. faces hardship with humor | |

| C. minimizes her responsibility for her past actions | |

| D. blames Mrs. Ansley for her own illness |

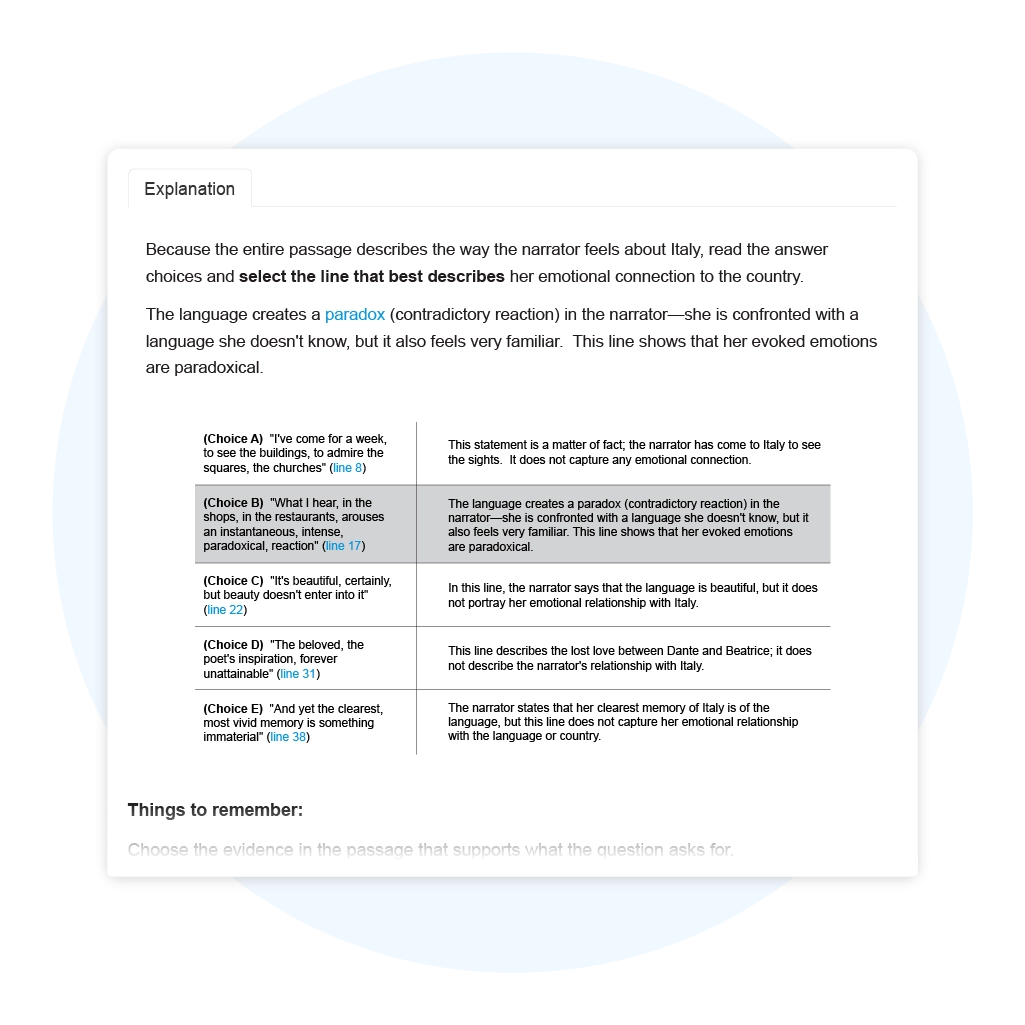

Explanation

Consider the events leading up to the paragraph along with the details in Mrs. Slade's comments. Select the answer that best describes what the comments reveal about Mrs. Slade.

| Details leading up to the comment | Mrs. Slade confesses that she, not Delphin, sent the letter to Mrs. Ansley and claims she did it as a joke. |

| Comment | Girls in love are "ferocious," and I even laughed to myself that night as I imagined you nervously waiting in the dark. However, I did feel bad when I heard you were ill. |

Mrs. Slade excuses her behavior by claiming that her actions weren't unusual; girls in love are "ferocious." She weakly attempts to appear compassionate by noting that she was "upset" when she discovered Mrs. Ansley's illness. Although she admits to sending the letter, she takes no responsibility for the pain she has caused, so her comments in the paragraph primarily suggest that she minimizes her responsibility for past actions.

(Choice A) Although Mrs. Slade claims she was upset by the news of Mrs. Ansley's illness, her attempts to downplay her actions and her admission that she laughed when she pictured Mrs. Ansley wandering around in the dark do not suggest she seeks forgiveness.

(Choice B) Mrs. Slade's prior comment that she sent the letter as a "joke" may suggest humor, but her comments in P6 lack humor.

(Choice D) Mrs. Slade's concern for Mrs. Ansley when she became ill suggests she doesn't blame Mrs. Ansley for her own illness.

Things to remember:

Consider the preceding details when determining what the comments in a paragraph suggest.

Passage: "The Tell-Tale Heart" by Edgar Allan Poe

The old man's hour had come! With a loud yell, I threw open the lantern and leaped into the room. He shrieked once—once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done. But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a muffled sound. This, however, did not vex me; it would not be heard through the wall. At length it ceased. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the corpse. Yes, he was stone, stone dead. I placed my hand upon the heart and held it there many minutes. There was no pulsation. He was stone dead. His eye would trouble me no more.

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence. First of all I dismembered the corpse. I cut off the head and the arms and the legs.

I then took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly, so cunningly, that no human eye—not even his—could have detected any thing wrong. There was nothing to wash out—no stain of any kind—no blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that. A tub had caught all—ha! ha!

When I had made an end of these labors, it was four o'clock—still dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart,—for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbour during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises.

I smiled,—for what had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them search—search well. I led them, at length, to his chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them here to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim.

The officers were satisfied. My manner had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat, and while I answered cheerily, they chatted of familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears: but still they sat and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct:—It continued and became more distinct: I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling: but it continued and gained definiteness—until, at length, I found that the noise was not within my ears.

No doubt I now grew very pale;—but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased—and what could I do? It was a low, dull, quick sound—much such a sound as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I gasped for breath—and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly—more vehemently; but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations; but the noise steadily increased. Why would they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observations of the men—but the noise steadily increased. Oh God! what could I do? I foamed—I raved—I swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louder—louder—louder! And still the men chatted pleasantly, and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God!—no, no! They heard!—they suspected!—they knew!—they were making a mockery of my horror!—this I thought, and this I think. But anything was better than this agony! Anything was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die! and now—again!—hark! louder! louder! louder! louder!

"Villains!" I shrieked, "dissemble no more! I admit the deed!—tear up the planks! here, here!—It is the beating of his hideous heart!"

Question

In line 30, the narrator's comment that he "talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice" indicates that he

| A. hopes to convince himself the noise is imaginary | |

| B. resents the officers' presence in the room | |

| C. is failing to maintain his outward composure | |

| D.is not able to locate the source of the sound |

Explanation

…I found that the noise was not within my ears.

No doubt I now grew very pale;—but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased—and what could I do?Read the comment within its context to determine what the comment indicates about the narrator.

The preceding line reveals that the narrator hears a noise he believes is real. This causes him to become frantic, worried that the officers hear it as well, so he begins to talk quickly and more loudly, yet his voice does not drown out the sound. He no longer feels composed and self-assured, and the phrase "talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice" indicates that the narrator is failing to maintain his outward composure.

(Choice A) The narrator's louder, quickening speech suggests he is trying to drown out the noise, which he believes is audible to the officers, rather than trying to convince himself it is a figment of his imagination.

(Choice B) The narrator talks loudly and quickly in order to conceal the sound from the officers, not because he resents their chatter and presence in the room. It is not until later that he wonders resentfully, "Why would they not be gone?"

(Choice D) Because the narrator believes that the noise is real, he talks to drown it out. He does not search for the source of the noise because he believes it to be coming from under the floorboards where he had concealed the body.

Things to remember:

Read the comment in its context to determine what it reveals about the narrator.

AP English Literature Practice Test: Setting

Passage: "Roman Fever" by Edith Wharton

"I wish now I hadn't told you. I'd no idea you'd feel about it as you do; I thought you'd be amused. It all happened so long ago, as you say; and you must do me the justice to remember that I had no reason to think you'd ever taken it seriously. How could I, when you were married to Horace Ansley two months afterward? As soon as you could get out of bed your mother rushed you off to Florence and married you. People were rather surprised—they wondered at its being done so quickly; but I thought I knew. I had an idea you did it out of pique—to be able to say you'd got ahead of Delphin and me. Kids have such silly reasons for doing the most serious things. And your marrying so soon convinced me that you'd never really cared."

"Yes. I suppose it would," Mrs. Ansley assented.

The clear heaven overhead was emptied of all its gold. Dusk spread over it, abruptly darkening the Seven Hills. Here and there lights began to twinkle through the foliage at their feet. Steps were coming and going on the deserted terrace—waiters looking out of the doorway at the head of the stairs, then reappearing with trays and napkins and flasks of wine. Tables were moved, chairs straightened. A feeble string of electric lights flickered out. A stout lady in a dustcoat suddenly appeared, asking in broken Italian if anyone had seen the elastic band which held together her tattered Baedeker*. She poked with her stick under the table at which she had lunched, the waiters assisting.

The corner where Mrs. Slade and Mrs. Ansley sat was still shadowy and deserted. For a long time neither of them spoke. At length Mrs. Slade began again: "I suppose I did it as a sort of joke—."

"A joke?"

"Well, girls are ferocious sometimes, you know. Girls in love especially. And I remember laughing to myself all that evening at the idea that you were waiting around there in the dark, dodging out of sight, listening for every sound, trying to get in—of course I was upset when I heard you were so ill afterward."

Mrs. Ansley had not moved for a long time. But now she turned slowly toward her companion.

"But I didn't wait. He'd arranged everything. He was there. We were let in at once," she said.

Mrs. Slade sprang up from her leaning position. "Delphin there! They let you in! Ah, now you're lying!" she burst out with violence.

Mrs. Ansley's voice grew clearer, and full of surprise. "But of course he was there. Naturally he came—."

"Came? How did he know he'd find you there? You must be raving!"

Mrs. Ansley hesitated, as though reflecting. "But I answered the letter. I told him I'd be there. So he came."

Mrs. Slade flung her hands up to her face. "Oh, God—you answered! I never thought of your answering...."

"It's odd you never thought of it, if you wrote the letter."

"Yes. I was blind with rage."

Mrs. Ansley rose, and drew her fur scarf about her. "It is cold here. We'd better go.... I'm sorry for you," she said, as she clasped the fur about her throat.

The unexpected words sent a pang through Mrs. Slade. "Yes; we'd better go." She gathered up her bag and cloak. "I don't know why you should be sorry for me," she muttered.

Mrs. Ansley stood looking away from her toward the dusky mass of the Colosseum. "Well— because I didn't have to wait that night."

Mrs. Slade gave an unquiet laugh. "Yes, I was beaten there. But I oughtn't to begrudge it to you, I suppose. At the end of all these years. After all, I had everything; I had him for twenty-five years. And you had nothing but that one letter that he didn't write."

Mrs. Ansley was again silent. At length she took a step toward the door of the terrace, and turned back, facing her companion.

"I had Barbara," she said, and began to move ahead of Mrs. Slade toward the stairway.

1. From ROMAN FEVER AND OTHER STORIES by Edith Wharton. Copyright © 1934 by Liberty Magazine. Copyright renewed © 1962 by William R. Tyler. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Question

In lines 9–16 ("The clear…deserted"), details about the setting emphasize Mrs. Slade's and Mrs. Ansley's

| A. mood of nostalgia | |

| B.sense of separation | |

| C. disregard for propriety | |

| D.feeling of expectancy |

Explanation

The clear heaven overhead was emptied of all its gold. Dusk spread over it, abruptly darkening the Seven Hills. Here and there lights began to twinkle through the foliage at their feet. Steps were coming and going on the deserted terrace—waiters looking out of the doorway at the head of the stairs, then reappearing with trays and napkins and flasks of wine. Tables were moved, chairs straightened. A feeble string of electric lights flickered out. A stout lady in a dustcoat suddenly appeared, asking in broken Italian if anyone had seen the elastic band which held together her tattered Baedeker*. She poked with her stick under the table at which she had lunched, the waiters assisting.

The corner where Mrs. Slade and Mrs. Ansley sat was still shadowy and deserted.

Look closely at the details of the scene, the events happening, and the description of the characters. Considering the passage as whole, draw a conclusion about what the setting emphasizes about Mrs. Ansley and Mrs. Slade.

The sky "emptied" of the sun, the "darkening of the Seven Hills," the electric lights that "flickered out," and the "deserted terrace" convey a sense of withdrawal, which reflects how the revelation of Mrs. Slade's deceit has caused them to briefly withdraw from their conversation. The movement on the terrace—"waiters looking out [and] reappearing with trays" and a lady "pok[ing] with her stick under the table"—contrasts with the women sitting silently in a corner that "was still shadowy and deserted."

The dark imagery and the contrast between the silent women and the surrounding movement underscore their separation from those around them as well as from each other, so the details about the setting emphasize Mrs. Slade's and Mrs. Ansley's sense of separation.

(Choice A) A person experiencing nostalgia thinks fondly about the past. It's unlikely that Mrs. Slade's confession of her deceitful actions, which were intended to hurt Mrs. Ansley, evoke fond memories for either woman.

(Choice C) Although Mrs. Ansley's secret, late-night meeting with Delphin when she was a young woman suggests a disregard for propriety (socially acceptable conduct), that detail is not revealed in relation to the lines describing the setting in the present.

(Choice D) The darkness surrounding the women and the fact they are sitting silently in a corner as darkness falls emphasizes a sense of separation, not expectancy (anticipation), as they both ponder Mrs. Slade's revelation and its implications.

Things to remember:

Consider the details of the setting and their relationship to the characters to determine what it emphasizes about the characters.

Passage: "The Tell-Tale Heart" by Edgar Allan Poe

The old man's hour had come! With a loud yell, I threw open the lantern and leaped into the room. He shrieked once—once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done. But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a muffled sound. This, however, did not vex me; it would not be heard through the wall. At length it ceased. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the corpse. Yes, he was stone, stone dead. I placed my hand upon the heart and held it there many minutes. There was no pulsation. He was stone dead. His eye would trouble me no more.

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence. First of all I dismembered the corpse. I cut off the head and the arms and the legs.

I then took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly, so cunningly, that no human eye—not even his—could have detected any thing wrong. There was nothing to wash out—no stain of any kind—no blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that. A tub had caught all—ha! ha!

When I had made an end of these labors, it was four o'clock—still dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart,—for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbour during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises.

I smiled,—for what had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them search—search well. I led them, at length, to his chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them here to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim.

The officers were satisfied. My manner had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat, and while I answered cheerily, they chatted of familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears: but still they sat and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct:—It continued and became more distinct: I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling: but it continued and gained definiteness—until, at length, I found that the noise was not within my ears.

No doubt I now grew very pale;—but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased—and what could I do? It was a low, dull, quick sound—much such a sound as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I gasped for breath—and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly—more vehemently; but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations; but the noise steadily increased. Why would they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observations of the men—but the noise steadily increased. Oh God! what could I do? I foamed—I raved—I swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louder—louder—louder! And still the men chatted pleasantly, and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God!—no, no! They heard!—they suspected!—they knew!—they were making a mockery of my horror!—this I thought, and this I think. But anything was better than this agony! Anything was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die! and now—again!—hark! louder! louder! louder! louder!

"Villains!" I shrieked, "dissemble no more! I admit the deed!—tear up the planks! here, here!—It is the beating of his hideous heart!"

Question

The attention the narrator pays to the details of sound serves primarily to

| A. create a symbol for the narrator's conscience | |

| B. provide the reader with a physical sense of the room | |

| C.indicate a shift in the narrative focus of the passage | |

| D. contrast with the narrator's mental deterioration |

Explanation

Note all the references to sound throughout the passage and determine what the details suggest about their purpose.

| P1 | The old man "shrieked once." |

| P4 | When the "bell sounded the hour," the officers knocked on the narrator's door. |

| P6 | The narrator heard "a ringing in [his] ears" that grew until he realized the "noise was not within my ears." |

| P7 | The narrator became more agitated and unhinged as the noise increased. |

| P8 | The narrator shrieked, "I admit the deed!" |

In P1 and P4, the sounds come from outside sources, and the narrator feels no guilt for his crime; however, when the noise begins in his head, he becomes frantic and eventually feels sure the officers know he has committed murder. As the sound grows, so do his panic and paranoia until his conscience forces him to confess. Therefore, the attention the narrator pays to the details of sound serves primarily to create a symbol for the narrator's conscience.

(Choice B) Because the sound of the dead man's heart beating is in the narrator's imagination, it provides insight into his mental state rather than a physical sense of the room.

(Choice C) Narrative focus refers to the topic of the passage. Because the topic—the description of both the narrator's crime and its effect on his mental state—doesn't change, the details about sound do not indicate a shift in focus.

(Choice D) The narrator's mental deterioration increases along with the sound's volume, suggesting a similarity between them, not a contrast.

Things to remember:

Examine the manner in which sound is described to determine its purpose in the passage.

Passage: Enduring Love by Ian McEwan

The beginning is simple to mark. We were in sunlight under a turkey oak, partly protected from a strong, gusty wind. I was kneeling on the grass with a corkscrew in my hand, and Clarissa was passing me the bottle—a 1987 Daumas Gassac*. This was the moment, this was the pinprick on the time map: I was stretching out my hand, and as the cool neck and the black foil touched my palm, we heard a man's shout. We turned to look across the field and saw the danger. Next thing, I was running toward it. The transformation was absolute: I don't recall dropping the corkscrew, or getting to my feet, or making a decision, or hearing the caution Clarissa called after me. What idiocy, to be racing into this story and its labyrinths, sprinting away from our happiness among the fresh spring grasses by the oak. There was the shout again, and a child's cry, enfeebled by the wind that roared in the tall trees along the hedgerows. I ran faster. And there, suddenly, from different points around the field, four other men were converging on the scene, running like me.

I see us from two hundred feet up, through the eyes of the buzzard we had watched earlier, soaring, circling, and dipping in the tumult of currents: five men running silently toward the center of a hundred-acre field. I approached from the southeast, with the wind at my back. About two hundred yards to my left two men ran side by side. They were farm laborers who had been repairing the fence along the field's southern edge where it skirts the road. The same distance beyond them was the motorist, John Logan, whose car was banked on the grass verge with its door, or doors, wide open. Knowing what I know now, it's odd to evoke the figure of Jed Parry directly ahead of me, emerging from a line of beeches on the far side of the field a quarter of a mile away, running into the wind. To the buzzard, Parry and I were tiny forms, our white shirts brilliant against the green, rushing toward each other like lovers, innocent of the grief this entanglement would bring. The encounter that would unhinge us was minutes away, its enormity disguised from us not only by the barrier of time but by the colossus in the center of the field, which drew us in with the power of a terrible ratio that set fabulous magnitude against the puny human distress at its base.

What was Clarissa doing? She said she walked quickly toward the center of the field. I don't know how she resisted the urge to run. By the time it happened, the event I am about to describe—the fall—she had almost caught us up and was well placed as an observer, unencumbered by participation, by the ropes and the shouting, and by our fatal lack of cooperation. What I describe is shaped by what Clarissa saw too, by what we told each other in the time of obsessive reexamination that followed: the aftermath, an appropriate term for what happened in a field waiting for its early summer mowing. The aftermath, the second crop, the growth promoted by that first cut in May.

I'm holding back, delaying the information. I'm lingering in the prior moment because it was a time when other outcomes were still possible; the convergence of six figures in a flat green space has a comforting geometry from the buzzard's perspective, the knowable, limited plane of the snooker table. The initial conditions, the force and the direction of the force, define all the consequent pathways, all the angles of collision and return, and the glow of the overhead light bathes the field, the baize and all its moving bodies, in reassuring clarity. I think that while we were still converging, before we made contact, we were in a state of mathematical grace. I linger on our dispositions, the relative distances and the compass point—because as far as these occurrences were concerned, this was the last time I understood anything clearly at all.

What were we running toward? I don't think any of us would ever know fully. But superficially the answer was a balloon. Not the nominal space that encloses a cartoon character's speech or thought, or, by analogy, the kind that's driven by mere hot air. It was an enormous balloon filled with helium, that elemental gas forged from hydrogen in the nuclear furnace of the stars, first step along the way in the generation of multiplicity and variety of matter in the universe, including our selves and all our thoughts.

We were running toward a catastrophe, which itself was a kind of furnace in whose heat identities and fates would buckle into new shapes. At the base of the balloon was a basket in which there was a boy, and by the basket, clinging to a rope, was a man in need of help.

Question

The narrator's description of the scene in lines 30–37 suggests that his recollection of the events is

| A. an analytical experience | |

| B. a painful effort | |

| C. an emotional epiphany | |

| D. a confused impression |

Explanation

Because the question asks what the narrator's description in P4 reveals about his recollection of running toward the balloon, consider the language he uses as he describes the events.

| Lines 30–37: |

|

In lines 30—37, the narrator describes the event with factual and scientific language, so the narrator's language suggests that his recollection of the events leading up to his arrival at the balloon is an analytical experience.

(Choice B) In these lines, the narrator deliberately holds back information, calmly stating that he is "linger[ing] on our dispositions" without feeling any pain in recollecting the scene.

(Choice C) An epiphany is a sudden, emotional realization, but the narrator's scientific language emphasizes his lack of emotion as he recollects running toward the balloon.

(Choice D) At the end of P4, the narrator claims that his arrival at the balloon "was the last time [he] understood anything clearly at all"; however, his recollection of the events leading up to that moment is characterized by clarity rather than confusion.

Things to remember:

Consider the details throughout the entire description to infer the narrator's attitude toward the situation.

AP English Literature Practice Test: Structure

Passage: Enduring Love by Ian McEwan

As a little boy Tip could be pinned into place by an idea. Set him on the floor with a picture book and he would stay until the book was finished. Set him on the floor with a can of Lincoln Logs1 and he would stay until he'd built himself a woody Taj Mahal2. Teddy, on the other hand, was more like a cloud. The slightest breath of wind could send him to the hall closet to hunt up a tennis racquet he hadn't seen in years, or out to the mailbox on the corner to see if the time for the pickup had changed even though he had nothing to mail. It wasn't that he refused to do his homework or even that he couldn't manage it, it was just that other things caught his attention, and anything that had Teddy's attention had all of him. Doyle got his youngest son through fourth grade the same way he would get him through fifth and sixth and all the grades to come: he sat there. He put his body in the room, at the table, beside the book. He brought Teddy to his office after school and had him sit beside him at the desk so they could work together. When Teddy's mind wandered from the project at hand, Doyle knew it before he did. He could smell the distraction as if it was something burning and he tapped the page with his finger. "Right here," Doyle would say. If Doyle had a meeting, a dinner out, he would pay Tip a dollar to take his place. He did not ask the baby-sitter to do it. She had a susceptibility to Teddy's charms that made her unsuitable for discipline.

The thing that was most likely to walk off with Teddy's concentration was the memory of his mother, the splendid redhead in the photographs, his own perpetual flame that he stoked with every available scrap of information. He did remember her. He was positive of that. He remembered her kneeling in front of him, buttoning his winter coat. He remembered sitting on the floor of the kitchen while she chopped carrots and talked to one of his aunts. He remembered lying beside her in a bed, his back to her chest, her long, pale arm draped over him so that he was looking at his pillow and her hand. He could still feel the even rhythm of her breathing. He had put his hand on top of her hand, stretched out his fingers and tried to cover hers, and in her sleep she wrapped that hand beneath him and pulled him close to her.

There were many, many times that Teddy tried to mine his father for information because surely Doyle had enough stored away to keep his memory burning forever, but Doyle would always just tap the open math book with his finger. "Right here."

It was in fact a misunderstanding between them. Teddy wanted to talk about Bernadette. Doyle wanted to keep Teddy from spending his life in the seventh grade. He tried to ask Tip but all Tip would ever say was, "I don't remember." He said it curtly, like Teddy was nagging and he didn't want to be bothered. That must have been the case since it was impossible that Tip, who was a year older and certainly smarter, would actually remember less. Sullivan would have told him about their mother, but Sullivan was never around and when he was around, he tended to stay in his room with the door locked. Other people in the family, aunts, uncles, various older cousins, would cry when he asked them what they remembered. They would pull the boy to their chest and weep in his hair until Doyle had to tell him not to ask anymore.

That was how he came to be so close to his great-uncle, Father Sullivan. It turned out the priest had stories stacked up like dinner napkins. Father Sullivan said that they belonged to Teddy, hundreds of stories waiting to be unfolded. They all started simply, beautifully, "When your mother was nine, she got a yellow dress for her birthday. I was at the party. Everything she asked for that year was yellow. She wanted a canary and a lemon cake."

Somewhere along the line Teddy's love for his mother had become his love for Father Sullivan, and his love for Father Sullivan became his love for God. The three of them were bound into an inextricable knot: the living and the dead and the life everlasting. Each one led him to the other, and any member of the trinity he loved simply increased his love for all three.

The question wasn't did he ever think of his mother. The question was did he ever think of anything else.

(2007)

1. from Run by Ann Patchett. Copyright (c) 2007 by Ann Patchett. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Question

The first three sentences of the passage serve to

| A. establish a point of reference for the details that follow | |

| B.provide examples of various childhood activities | |

| C. evoke nostalgic images of a simpler, more innocent time | |

| D. introduce a conflict between two characters |

Explanation

Summarize the first three sentences and compare them with the rest of the text to determine how they function within the passage.

| First three sentences: | Tip could play with one toy contentedly for long periods of time. |

| Rest of the passage: | Unlike Tip, Teddy often drifted from one activity to another and was easily distracted. |

The first three sentences describe Tip's ability to concentrate on one thing, which is followed by details about Teddy's distracted behavior, illustrating a sharp contrast between the brothers. The description of Tip provides a point of reference (context provided to help explain something else) for the reader to better comprehend Teddy's preoccupied nature, so the first three sentences establish a point of reference for the details that follow.

(Choice B) The activities described are unique to Tip, rather than general examples of childhood activities.

(Choice C) The childhood toys mentioned could suggest innocence; however, the narrator describes Tip's behavior to create a contrast with Teddy's nature, not to evoke nostalgic (sentimental) images.

(Choice D) Tip and Teddy have contrasting natures, but the passage's details don't suggest that this contrast causes a conflict between the two characters.

Things to remember:

Compare the indicated sentences with the information that follows to establish the purpose of the sentences.

Passage: "Birches" by Robert Frost

When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy's been swinging them.

But swinging doesn't bend them down to stay

As ice-storms do. Often you must have seen them

Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning

After a rain. They click upon themselves

As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored

As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.

Soon the sun's warmth makes them shed crystal shells

Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust—

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You'd think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.

They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,

And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed

So low for long, they never right themselves:

You may see their trunks arching in the woods

Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground

Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

But I was going to say when Truth broke in

With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm

I should prefer to have some boy bend them

As he went out and in to fetch the cows—

Some boy too far from town to learn baseball,

Whose only play was what he found himself,

Summer or winter, and could play alone.

One by one he subdued his father's trees

By riding them down over and over again

Until he took the stiffness out of them,

And not one but hung limp, not one was left

For him to conquer. He learned all there was

To learn about not launching out too soon

And so not carrying the tree away

Clear to the ground. He always kept his poise

To the top branches, climbing carefully

With the same pains you use to fill a cup

Up to the brim, and even above the brim.

Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish,

Kicking his way down through the air to the ground.

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

And so I dream of going back to be.

It's when I'm weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig's having lashed across it open.

I'd like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth's the right place for love:

I don't know where it's likely to go better.

I'd like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

(1916)

1. Frost, Robert. "Birches." The Poetry of Robert Frost. New York. Henry Holt. 1916.

Question

Which of the following best describes the function of lines 21–27 ("But I…alone") in the context of the poem as a whole?

| A. They interrupt the poem to create wonder and appreciation for the ice-storm. | |

| B. They interrupt the poem to emphasize the harshness of the ice-storm and its effects. | |

| C. They return the poem to its initial contrast of darker trees and birches. | |

| D. They return the poem to its focus on the significance of swinging on the birches. |

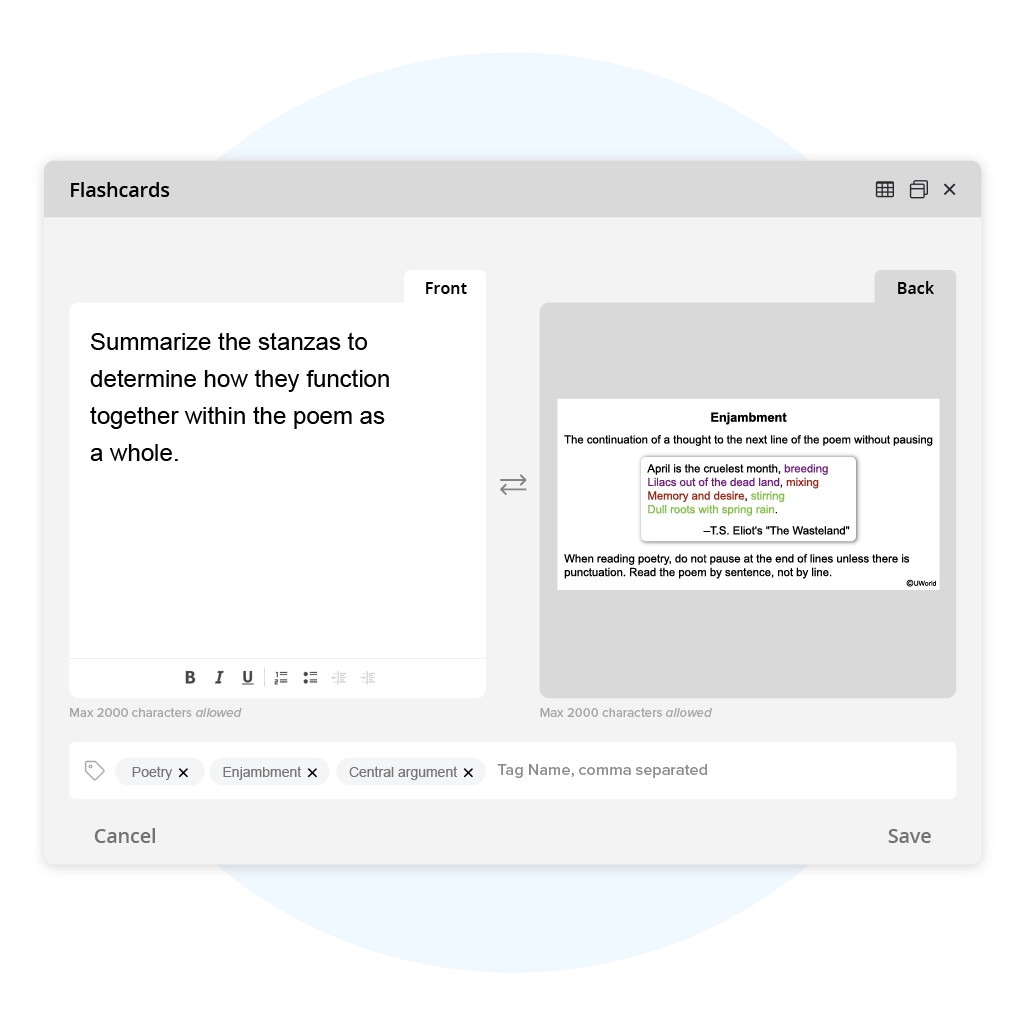

Explanation

Summarize the lines in question and the lines that come before and after them. Then note the relationship between them.

| Lines before: | The speaker "likes to think some boy's been swinging" the birches, then interrupts his thoughts about the boy to describe the ice-storm and its effects on the trees. |

| Lines 21–27 | The speaker states, "But I was going to say" and returns to his preference for a boy's bending the birches. |

| Lines after: | The speaker describes how a boy swings on birches, which the speaker uses to convey his insight about life to the reader. |

Thus, lines 21–27 function to return the poem to its focus on the significance of swinging on the birches.

(Choices A and B) The description of the ice storm is what interrupts the speaker. He then returns to what he "was going to say…[he] should prefer some boy bend them" and its significance.

(Choice C) The speaker returns to his preference for a boy's bending the birch trees in these lines; after the second line, he doesn't mention the darker trees.

Things to remember:

Identify the function of a poem's lines by looking at their relationship to the lines that come before and after them.

Passage: "Birches" by Robert Frost

Ma used to soak wounds in salt water and pack them with mud mixed with all kinds of potions. There was no salt in the kitchen, so Kya limped into the woods toward a brackish slipstream so salty at low tide, its edges glistened with brilliant white crystals. She sat on the ground, soaking her foot in the marsh's brine, all the while moving her mouth: open, close, open, close, mocking yawns, chewing motions, anything to keep it from jamming up. After nearly an hour, the tide receded enough for her to dig a hole in the black mud with her fingers, and she eased her foot into the silky earth. The air was cool here, and eagle cries gave her bearing.

By late afternoon she was very hungry, so went back to the shack. Pa's room was still empty, and he probably wouldn't be home for hours. Playing poker and drinking whiskey kept a man busy most of the night. There were no grits, but rummaging around, she found an old greasy tin of Crisco shortening, dipped up a tiny bit of the white fat, and spread it on a soda cracker. Nibbled at first, then ate five more.

She eased into her porch bed, listening for Pa's boat. The approaching night tore and darted and sleep came in bits, but she must have dropped off near morning for she woke with the sun fully on her face. Quickly she opened her mouth; it still worked. She shuffled back and forth from the brackish pool to the shack until, by tracking the sun, she knew two days had passed. She opened and closed her mouth. Maybe she had made it.

That night, tucking herself into the sheets of the floor mattress, her mud-caked foot wrapped in a rag, she wondered if she would wake up dead. No, she remembered, it wouldn't be that easy: her back would bow; her limbs twist.

A few minutes later, she felt a twinge in her lower back and sat up. "Oh no, oh no. Ma, Ma." The sensation in her back repeated itself and made her hush. "It's just an itch," she muttered. Finally, truly exhausted, she slept, not opening her eyes until doves murmured in the oak.

She walked to the pool twice a day for a week, living on saltines and Crisco, and Pa never came the whole time. By the eighth day she could circle her foot without stiffness and the pain had retreated to the surface. She danced a little jig, favoring her foot, squealing, "I did it, I did it!"

The next morning, she headed for the beach to find more pirates.

"First thing I'm gonna do is boss my crew to pick up all them nails."

****

Every morning she woke early, still listening for the clatter of Ma's busy cooking. Ma's favorite breakfast had been scrambled eggs from her own hens, ripe red tomatoes sliced, and cornbread fritters made by pouring a mixture of cornmeal, water, and salt onto grease so hot the concoction bubbled up, the edges frying into crispy lace. Ma said you weren't really frying something unless you could hear it crackling from the next room, and all her life Kya had heard those fritters popping in grease when she woke. Smelled the blue, hot-corn smoke. But now the kitchen was silent, cold, and Kya slipped from her porch bed and stole to the lagoon.

Months passed, winter easing gently into place, as southern winters do. The sun, warm as a blanket, wrapped Kya's shoulders, coaxing her deeper into the marsh. Sometimes she heard night-sounds she didn't know or jumped from lightning too close, but whenever she stumbled, it was the land that caught her. Until at last, at some unclaimed moment, the heart-pain seeped away like water into sand. Still there, but deep. Kya laid her hand upon the breathing, wet earth, and the marsh became her mother.

(2018)

1. Excerpt from WHERE THE CRAWDADS SING by Delia Owens, copyright © 2017 by Delia Owens. Used by permission of G. P. Putnam's Sons, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Question

The passage primarily focuses on the

| A. fears Kya encounters at night during her parents' absence | |

| B.challenges Kya faces in responding to her parents' personalities | |

| C. physical and mental worlds of Kya in her parents' absence | |

| D.misfortune brought upon the family by the primitive environment |

Explanation

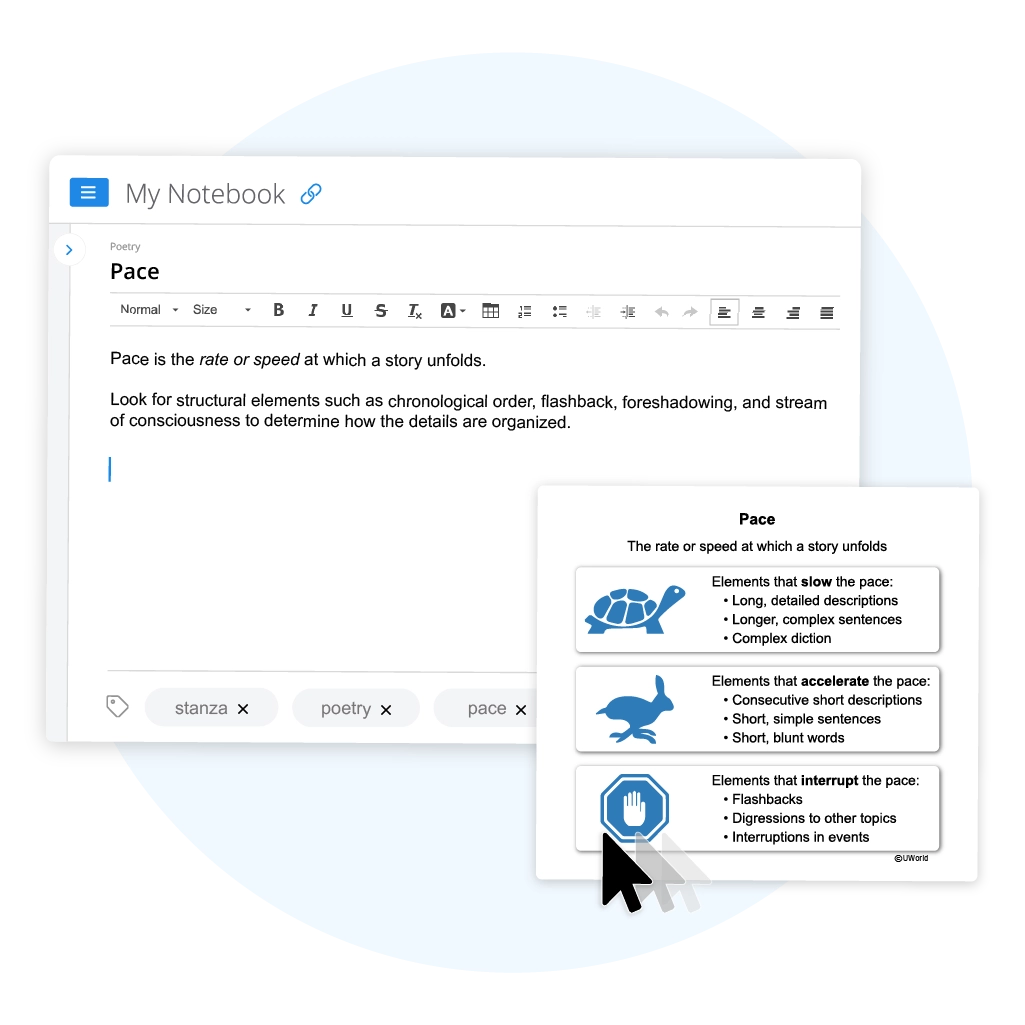

Summarize the passage's paragraphs, and then select the answer with the most evidence from the passage.

| P1–P4: | Kya acts to avoid tetanus and thinks about whether she will survive on her own. |

| P5–P6: | Kya fears the twinges in her back and feels joy that she survived her foot injury. |

| P7–P8: | Kya resumes her fantasies about pirates and vows to avoid nails. |

| P9: | Kya remembers her absent mother's cooking and later travels alone to the lagoon. |

| P10: | Kya is attracted to the marsh, feels momentary fear, and is then adopted by the marsh. |

A summary of the passage indicates that the plot focuses most on what Kya does and thinks throughout her solitary ordeal and its aftermath. The large amount of evidence points to the passage's primary focus as the physical and mental worlds of Kya in her parents' absence.

(Choice A) Kya does experience fears at night in P4, P5, and P10, but the majority of the passage focuses on other mental reactions (joy, fantasy, memories) and physical experiences (hunger, survival, the marsh).

(Choice B) The passage contains little description of Kya's parents' personalities. Moreover, the primary focus is on Kya's actions and thoughts in response to her injury rather than to her parents' personalities.

(Choice D) Kya suffers misfortune—injury, hunger, and abandonment—but these are brought on by accident and by her parents' absence more than by the primitiveness (undeveloped state) of the environment.

Things to remember:

Look for evidence of the passage's main focus by summarizing the actions and thoughts of the character(s).

AP English Literature Practice Test: Narration

Passage: The Awakening by Kate Chopin

Madame Ratignolle laid her hand over that of Mrs. Pontellier, which was near her. Seeing that the hand was not withdrawn, she clasped it firmly and warmly. She even stroked it a little, fondly, with the other hand, murmuring in an undertone, "Pauvre Cherie1."

The action was at first a little confusing to Edna, but she soon lent herself readily to the Creole's2 gentle caress. She was not accustomed to an outward and spoken expression of affection, either in herself or in others. She and her younger sister, Janet, had quarreled a good deal through force of unfortunate habit. Her older sister, Margaret, was matronly and dignified, probably from having assumed matronly and housewifely responsibilities too early in life, their mother having died when they were quite young. Margaret was not effusive; she was practical. Edna had had an occasional girl friend, but whether accidentally or not, they seemed to have been all of one type—the self-contained. She never realized that the reserve of her own character had much, perhaps everything, to do with this. Her most intimate friend at school had been one of rather exceptional intellectual gifts, who wrote fine-sounding essays, which Edna admired and strove to imitate; and with her she talked and glowed over the English classics, and sometimes held religious and political controversies.

Edna often wondered at one propensity which sometimes had inwardly disturbed her without causing any outward show or manifestation on her part. At a very early age—perhaps it was when she traversed the ocean of waving grass—she remembered that she had been passionately enamored of a dignified and sad-eyed cavalry officer who visited her father in Kentucky. She could not leave his presence when he was there, nor remove her eyes from his face, which was something like Napoleon's, with a lock of black hair failing across the forehead. But the cavalry officer melted imperceptibly out of her existence.

At another time her affections were deeply engaged by a young gentleman who visited a lady on a neighboring plantation. It was after they went to Mississippi to live. The young man was engaged to be married to the young lady, and they sometimes called upon Margaret, driving over of afternoons in a buggy. Edna was a little miss, just merging into her teens; and the realization that she herself was nothing, nothing, nothing to the engaged young man was a bitter affliction to her. But he, too, went the way of dreams.

She was a grown young woman when she was overtaken by what she supposed to be the climax of her fate. It was when the face and figure of a great tragedian began to haunt her imagination and stir her senses. The persistence of the infatuation lent it an aspect of genuineness. The hopelessness of it colored it with the lofty tones of a great passion.

The picture of the tragedian stood enframed upon her desk. Any one may possess the portrait of a tragedian without exciting suspicion or comment. (This was a sinister reflection which she cherished.) In the presence of others she expressed admiration for his exalted gifts, as she handed the photograph around and dwelt upon the fidelity of the likeness. When alone she sometimes picked it up and kissed the cold glass passionately.

Her marriage to Leonce Pontellier was purely an accident, in this respect resembling many other marriages which masquerade as the decrees of Fate. It was in the midst of her secret great passion that she met him. He fell in love, as men are in the habit of doing, and pressed his suit with an earnestness and an ardor which left nothing to be desired. He pleased her; his absolute devotion flattered her. She fancied there was a sympathy of thought and taste between them, in which fancy she was mistaken. Add to this the violent opposition of her father and her sister Margaret to her marriage with a Catholic, and we need seek no further for the motives which led her to accept Monsieur Pontellier for her husband.

The acme of bliss, which would have been a marriage with the tragedian, was not for her in this world. As the devoted wife of a man who worshiped her, she felt she would take her place with a certain dignity in the world of reality, closing the portals forever behind her upon the realm of romance and dreams.

But it was not long before the tragedian had gone to join the cavalry officer and the engaged young man and a few others; and Edna found herself face to face with the realities. She grew fond of her husband, realizing with some unaccountable satisfaction that no trace of passion or excessive and fictitious warmth colored her affection, thereby threatening its dissolution.

(1899)

Question

Mrs. Pontellier's feelings are communicated primarily through which technique of third person narration?

| A.Actions by Mrs. Pontellier illustrating her discontent | |

| B.Explicit statements made by other characters | |

| C. Observations by the narrator about her history | |

| D. Descriptions of how the characters contribute to Mrs. Pontellier's melancholy |

Explanation

Third person narration is a narrator telling a story about someone else. Ask how the narrator communicates Mrs. Pontellier's feelings.

| P1–P3 | The narrator introduces Edna's history and relationships with family and friends. |

| P4–P6 | The narrator describes the "bitter affliction" that Edna felt by always being overlooked by potential suitors. |

| P7–P9 | The narrator tells the reader that Edna married Leonce Pontellier as "an accident" and shares Mrs. Pontellier's inner thoughts that the possibility of "romance and dreams" was "closing…forever." |

Mrs. Pontellier's background is described from an outsider's perspective. By summarizing the paragraphs, it can be concluded that Mrs. Pontellier's feelings are communicated primarily through observations by the narrator about her history.

(Choice A) Although the narrator does recount the actions of Mrs. Pontellier and her obsessions, the narrator does not primarily use actions to illustrate discontent. Rather, it is Mrs. Pontellier's conveyed thoughts that reveal her unhappiness.

(Choice B) Other than two words uttered by Madame Ratignolle in P1, there are no other explicit statements made by other characters, so this cannot be the primary technique that reveals Mrs. Pontellier's feelings.

(Choice D) Although the passage has descriptions of other characters, there is no evidence that Mrs. Pontellier experiences melancholy (depression) as a direct result of these characters.

Things to remember:

Ask how the narrator reveals something specific by using a particular technique.

Passage: "Roman Fever" by Edith Wharton

"I wish now I hadn't told you. I'd no idea you'd feel about it as you do; I thought you'd be amused. It all happened so long ago, as you say; and you must do me the justice to remember that I had no reason to think you'd ever taken it seriously. How could I, when you were married to Horace Ansley two months afterward? As soon as you could get out of bed your mother rushed you off to Florence and married you. People were rather surprised—they wondered at its being done so quickly; but I thought I knew. I had an idea you did it out of pique—to be able to say you'd got ahead of Delphin and me. Kids have such silly reasons for doing the most serious things. And your marrying so soon convinced me that you'd never really cared."

"Yes. I suppose it would," Mrs. Ansley assented.

The clear heaven overhead was emptied of all its gold. Dusk spread over it, abruptly darkening the Seven Hills. Here and there lights began to twinkle through the foliage at their feet. Steps were coming and going on the deserted terrace—waiters looking out of the doorway at the head of the stairs, then reappearing with trays and napkins and flasks of wine. Tables were moved, chairs straightened. A feeble string of electric lights flickered out. A stout lady in a dustcoat suddenly appeared, asking in broken Italian if anyone had seen the elastic band which held together her tattered Baedeker*. She poked with her stick under the table at which she had lunched, the waiters assisting.

The corner where Mrs. Slade and Mrs. Ansley sat was still shadowy and deserted. For a long time neither of them spoke. At length Mrs. Slade began again: "I suppose I did it as a sort of joke—."

"A joke?"

"Well, girls are ferocious sometimes, you know. Girls in love especially. And I remember laughing to myself all that evening at the idea that you were waiting around there in the dark, dodging out of sight, listening for every sound, trying to get in—of course I was upset when I heard you were so ill afterward."

Mrs. Ansley had not moved for a long time. But now she turned slowly toward her companion.

"But I didn't wait. He'd arranged everything. He was there. We were let in at once," she said.

Mrs. Slade sprang up from her leaning position. "Delphin there! They let you in! Ah, now you're lying!" she burst out with violence.

Mrs. Ansley's voice grew clearer, and full of surprise. "But of course he was there. Naturally he came—."

"Came? How did he know he'd find you there? You must be raving!"

Mrs. Ansley hesitated, as though reflecting. "But I answered the letter. I told him I'd be there. So he came."

Mrs. Slade flung her hands up to her face. "Oh, God—you answered! I never thought of your answering...."

"It's odd you never thought of it, if you wrote the letter."

"Yes. I was blind with rage."

Mrs. Ansley rose, and drew her fur scarf about her. "It is cold here. We'd better go.... I'm sorry for you," she said, as she clasped the fur about her throat.

The unexpected words sent a pang through Mrs. Slade. "Yes; we'd better go." She gathered up her bag and cloak. "I don't know why you should be sorry for me," she muttered.

Mrs. Ansley stood looking away from her toward the dusky mass of the Colosseum. "Well— because I didn't have to wait that night."

Mrs. Slade gave an unquiet laugh. "Yes, I was beaten there. But I oughtn't to begrudge it to you, I suppose. At the end of all these years. After all, I had everything; I had him for twenty-five years. And you had nothing but that one letter that he didn't write."

Mrs. Ansley was again silent. At length she took a step toward the door of the terrace, and turned back, facing her companion.

"I had Barbara," she said, and began to move ahead of Mrs. Slade toward the stairway.

1. From ROMAN FEVER AND OTHER STORIES by Edith Wharton. Copyright © 1934 by Liberty Magazine. Copyright renewed © 1962 by William R. Tyler. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Question

Mrs. Slade's feelings are communicated primarily through which technique of third-person narration?

| A. Explicit statements of her emotions made by the narrator | |

| B. Observations made by Mrs. Ansley about Mrs. Slade's deceit | |

| C. Conjecture by the narrator about her confused state of mind | |

| D. Comments by Mrs. Slade that indicate her mental state |

Explanation

A third-person narrator relates details and events as an outsider looking in through the eyes of one or more characters. Examine the details that relate how Mrs. Slade feels throughout the passage to determine how the narrator communicates those feelings.

The narrator does not describe many of Mrs. Slade's actions. Instead, her feelings are conveyed primarily through her comments:

- "I wish I hadn't told you."

- "I [wrote the letter] as a sort of joke–."

- "…of course I was upset when I heard you were so ill afterward."

- "Now you are lying!"

- "You must be raving [insane]!"

- "I was blind with rage."

Mrs. Slade's many comments describing her actions and outrage indicate that the technique the third-person narrator uses to communicate Mrs. Slade's feelings is comments by Mrs. Slade that indicate her state of mind.

(Choice A) Mrs. Slade, not the narrator, explicitly (specifically) states how she feels with comments such as "I was blind with rage" and "I was upset."

(Choice B) Mrs. Ansley does not make observations about Mrs. Slade's deceit. Instead, she reacts to Mrs. Slade's revelations about the incident from their youth.

(Choice C) A conjecture is an inference formed without proof. Although in P1 Mrs. Slade makes conjectures about the other woman's reasons for a quick marriage, the narrator does not present inferences to explain Mrs. Slade's confusion when she discovers Delphin actually met Mrs. Ansley at the Colosseum.

Things to remember:

Examine the details that reveal the character's emotions to determine the technique used to communicate them.

Passage: "The Tell-Tale Heart" by Edgar Allan Poe

The old man's hour had come! With a loud yell, I threw open the lantern and leaped into the room. He shrieked once—once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done. But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a muffled sound. This, however, did not vex me; it would not be heard through the wall. At length it ceased. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the corpse. Yes, he was stone, stone dead. I placed my hand upon the heart and held it there many minutes. There was no pulsation. He was stone dead. His eye would trouble me no more.

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence. First of all I dismembered the corpse. I cut off the head and the arms and the legs.

I then took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly, so cunningly, that no human eye—not even his—could have detected any thing wrong. There was nothing to wash out—no stain of any kind—no blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that. A tub had caught all—ha! ha!

When I had made an end of these labors, it was four o'clock—still dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart,—for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbour during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises.

I smiled,—for what had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them search—search well. I led them, at length, to his chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them here to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim.

The officers were satisfied. My manner had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat, and while I answered cheerily, they chatted of familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears: but still they sat and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct:—It continued and became more distinct: I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling: but it continued and gained definiteness—until, at length, I found that the noise was not within my ears.

No doubt I now grew very pale;—but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased—and what could I do? It was a low, dull, quick sound—much such a sound as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I gasped for breath—and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly—more vehemently; but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations; but the noise steadily increased. Why would they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observations of the men—but the noise steadily increased. Oh God! what could I do? I foamed—I raved—I swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louder—louder—louder! And still the men chatted pleasantly, and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God!—no, no! They heard!—they suspected!—they knew!—they were making a mockery of my horror!—this I thought, and this I think. But anything was better than this agony! Anything was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die! and now—again!—hark! louder! louder! louder! louder!

"Villains!" I shrieked, "dissemble no more! I admit the deed!—tear up the planks! here, here!—It is the beating of his hideous heart!"

Question

The passage primarily suggests that

| A. as the narrator's paranoia increases, his methodical efforts to hide evidence have failed | |

| B. when the narrator talks with the police officers, he worries that the old man is still alive | |

| C. as the narrator begins to hear the beating sound, he starts to fear a severe punishment | |

| D. although the narrator emphatically asserts his sanity, his actions contradict this claim |

Explanation

Briefly summarize the paragraphs and select the answer that best describes what happens in the passage.

| P1 | The narrator describes the methodical killing of the old man. |

| P2–P3 | To prove he is not "mad" (insane), the narrator describes the methodical dismemberment and concealment of the body and laughs, "ha! ha!"—revealing his morbid excitement. |

| P4–P5 | When the police knock on the door, he claims he has nothing "to fear." He considers his actions both bold and triumphant. |

| P6–P8 | The narrator begins to hear what he believes to be the old man's beating heart. As his paranoia increases, his actions become wilder until he is so deranged that he feels he must confess. |

The narrator claims he is not "mad"; however, his methodical killing of the old man and concealing of the body, accompanied by his gleeful attitude, suggest he may actually be insane. Therefore, the passage primarily suggests that although the narrator emphatically asserts his sanity, his actions contradict this claim.

(Choice A) Although the narrator comes to believe that the sound he hears must have alerted the officers to the body, he notes, "And still the men chatted pleasantly, and smiled," suggesting they are convinced no crime was committed. This means he was successful in hiding the evidence.

(Choice B) In his deranged state, the narrator worries that the beating sound will alert the officers to his crime, not that the dismembered old man could possibly be alive.

(Choice C) Although the narrator's behavior becomes more agitated, he does not mention any fear of punishment. Instead, the final confession and revelation of "the beating of [the old man's] hideous heart" suggest he is more upset by the officers' "mockery of [his] horror."

Things to remember:

Summarize the paragraphs to determine which answer choice is suggested by the passage as a whole.

AP English Literature Practice Test: Figurative Language

Passage: The Awakening by Kate Chopin

Madame Ratignolle laid her hand over that of Mrs. Pontellier, which was near her. Seeing that the hand was not withdrawn, she clasped it firmly and warmly. She even stroked it a little, fondly, with the other hand, murmuring in an undertone, "Pauvre Cherie1."

The action was at first a little confusing to Edna, but she soon lent herself readily to the Creole's2 gentle caress. She was not accustomed to an outward and spoken expression of affection, either in herself or in others. She and her younger sister, Janet, had quarreled a good deal through force of unfortunate habit. Her older sister, Margaret, was matronly and dignified, probably from having assumed matronly and housewifely responsibilities too early in life, their mother having died when they were quite young. Margaret was not effusive; she was practical. Edna had had an occasional girl friend, but whether accidentally or not, they seemed to have been all of one type—the self-contained. She never realized that the reserve of her own character had much, perhaps everything, to do with this. Her most intimate friend at school had been one of rather exceptional intellectual gifts, who wrote fine-sounding essays, which Edna admired and strove to imitate; and with her she talked and glowed over the English classics, and sometimes held religious and political controversies.

Edna often wondered at one propensity which sometimes had inwardly disturbed her without causing any outward show or manifestation on her part. At a very early age—perhaps it was when she traversed the ocean of waving grass—she remembered that she had been passionately enamored of a dignified and sad-eyed cavalry officer who visited her father in Kentucky. She could not leave his presence when he was there, nor remove her eyes from his face, which was something like Napoleon's, with a lock of black hair failing across the forehead. But the cavalry officer melted imperceptibly out of her existence.

At another time her affections were deeply engaged by a young gentleman who visited a lady on a neighboring plantation. It was after they went to Mississippi to live. The young man was engaged to be married to the young lady, and they sometimes called upon Margaret, driving over of afternoons in a buggy. Edna was a little miss, just merging into her teens; and the realization that she herself was nothing, nothing, nothing to the engaged young man was a bitter affliction to her. But he, too, went the way of dreams.

She was a grown young woman when she was overtaken by what she supposed to be the climax of her fate. It was when the face and figure of a great tragedian began to haunt her imagination and stir her senses. The persistence of the infatuation lent it an aspect of genuineness. The hopelessness of it colored it with the lofty tones of a great passion.

The picture of the tragedian stood enframed upon her desk. Any one may possess the portrait of a tragedian without exciting suspicion or comment. (This was a sinister reflection which she cherished.) In the presence of others she expressed admiration for his exalted gifts, as she handed the photograph around and dwelt upon the fidelity of the likeness. When alone she sometimes picked it up and kissed the cold glass passionately.