ACT® Sample Reading Test Questions

Free Sample ACT Reading Test Questions

Passage A by Kate Flint

All photography requires light, but the light used in flash photography is unique—shocking, intrusive, and abrupt. Unlike the light that comes from the sun, or even from ambient illumination, flash explodes suddenly into the darkness.

In the early days of flash photography, a sense of quasi-divine revelation was invoked by some flash photographers, especially when documenting deplorable social conditions. The filthy darkness in which the urban poor lived could not have been photographed otherwise. Jacob Riis, working in New York in the late 1880s, used spiritual language to underscore flash's significance as an instrument to expose—and hopefully rectify—the horrid conditions of those living in urban squalor.

It's in relation to documentary photography that we most starkly encounter flash's contradictory aspects. It makes visible that which would otherwise remain in darkness; to do so requires an intrusion, a rupturing of private lives and interiors. Yet flash brings a form of democracy to the material world. Formerly insignificant details take on unplanned prominence, as we see in the work of those Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers who used flash in the 1930s and laid bare the reality of poverty during the Depression. A sudden flare of light reveals each dent on a kitchen utensil and the label on each carefully stored can; each cherished ornament on the mantle; each wrinkle of the skin.

These FSA photographers used flash bulbs, not powder. Pioneered in the late 1920s, these bulbs became generally available around 1930, their ease and portability transforming the abilities of press photographers, documentarians, even police photographers, who could now record evidence of crimes committed under the cover of darkness. But the history of flash photography is about speed as well as light. The breathtaking, high-speed images produced by Harold Edgerton in the mid-20th century, enabled by very high-speed bursts of light from electrically-controlled neon tubes, created the illusion of stopped motion: bullets piercing playing cards or balloons; golfers and tennis players swinging at balls. The ordinary became strange and beautiful through stroboscopic flash.

These examples challenge the bad press that flash photography has received over the century and a half since its invention. Sudden and surprising light continues to be imaginatively deployed by inventive photographers, once again making luminous something of the original wonder that attended flash.

Passage B by Kate Flint

Susan Sontag was deliberately provocative when she coupled photography with violence. There is, she wrote in 1977, "something predatory in the act of taking a picture." She pointed out that we speak casually about "loading" and "aiming" a camera: "Just as the camera is a sublimation of a gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated violation of privacy." Sontag's hyperbole prodded her readers to consider the identity-freezing that is implicit in each portrait that is shot.

But it is less of an exaggeration to couple violence with one particular photographic technology: flash. From the earliest decades of flash photography, when limelight or magnesium was used to illuminate darkness, flash was associated with explosive unpredictability. Even after flash powder was invented in 1887, accidents were commonplace, maiming and injuring photographers. Not until flash bulbs were introduced around 1930 did the means for producing sudden blasts of artificial light become easier and more dependable, and this increased with the advent of the Speedlite and other electronic flash guns.

"Flash gun"—that nomenclature takes us full circle, since some of the early contraptions for igniting flash powder indeed looked much like a revolver. The name, and the linkage to violence and weaponry, stuck. The allusion is clear in the black humor of the words that decorated some military gun barrels in World War II: "Smile. Wait for flash." Weaponry and photography work in consort in Alfred Hitchcock's film Foreign Correspondent, in which a man posing as a news photographer fires a weapon at the same moment that he sets off his camera flash.

Flash can also enact a form of ethical violence. Among those who worked for the Farm Security Administration during the Depression, Dorothea Lange saw its use as invasive, and Ben Shahn expressed his doubts--both about photographing someone else's private space and about flash's aesthetics. "When some of the people came in and began to use flash I thought it was immoral," he said. "You know, you come into a sharecropper's cabin and it's dark. But a flash destroyed that darkness." Another photographic artist, Henri Cartier-Bresson, also shunned the flash, in part due to its association with newsmen and detective work. No one more famously brought flash and crime together than the man known as Weegee, working in mid-20th-century New York to record criminal activity. "A photographer is a hunter with a camera," he said, anticipating Sontag.

Nowhere has this determined violation and exploitation been more apparent than in the work of paparazzi. Popping flash bulbs have become visual shorthand for the achievement of notoriety, as well as the price paid for that fame. Think of King Kong—captured, brought to New York City, exhibited on stage, and then startled into destructive rage by newspaper photographers. Whether viewed as exposure or exploitation, flash photography is historically, and disconcertingly, inseparable from violence.

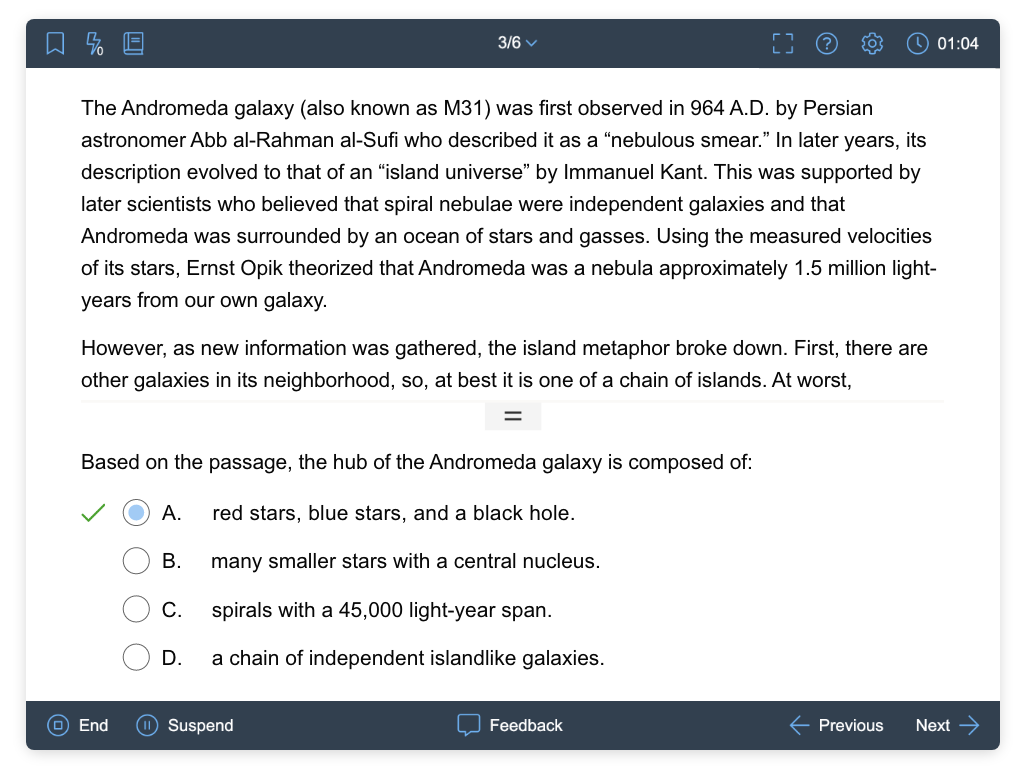

Question

In Passage B, the main purpose of the details about military gun barrels in lines 38–40 is to:

| A. describe an attempt by the military to improve its public image by using flash photography. | |

| B. explain some people's perceptions of the immorality in flash photography. | |

| C. emphasize the positive connotations of flash photography that emerged during World War II. | |

| D. provide evidence of the association between flash photography and destruction. |

Explanation

P3: "Flash gun"—that nomenclature takes us full circle, since some of the early contraptions for igniting flash powder indeed looked much like a revolver. The name, and the linkage to violence and weaponry, stuck. The allusion is clear in the black humor of the words that decorated some military gun barrels in World War II: "Smile. Wait for flash."

In this question, the purpose of a detail refers to what the detail does. Read the text around the detail specified in the question to understand the idea it represents. Then, test each answer choice to see which one best describes what the detail contributes to the passage.

In the preceding lines, flash photography is described as having

- "Flash guns" that look "much like a revolver"

- A name linked to "violence and weaponry"

The description of the gun barrels in lines 38–40 shows a reference to flash photography—"Smile. Wait for flash"—being used in the context of military weapons. Therefore, these details provide evidence of the association between flash photography and destruction.

(Choice A) P3 doesn't discuss the military trying to improve its image. Instead, it shows that people recognized the connection between flash photography and weapons.

(Choice B) Although P4 discusses Shahn's feelings that flash was "immoral," P3 does not. A detail's purpose must connect to the surrounding text.

(Choice C) P3 examines the negative connotations (emotional connections) that emerged during World War II—through the "black humor" of the words on military gun barrels—and does not discuss any positive connotations between the two.

Things to remember:

For a question about a detail's primary purpose, put the detail in context to understand the complete idea. Then, choose the answer that best describes how the detail helps the author illustrate a key point in the passage.

Passage

INFORMATIONAL: This passage is adapted from the article "Octopuses are Smart Suckers!?" by Jennifer Mather (© 2000 by Jennifer Mather).

While watching an octopus in Bermuda, animal behaviorist Jennifer Mather observed it sitting in its sheltering den after a foraging expedition, where it caught several crabs, took them home, and ate them. Suddenly it jetted out directly to a small rock about six feet away, tucked it under its spread arms and jetted back. Going out three times more in different directions, it took up three more rocks and piled the resulting barrier in front of the entrance to its den and went to sleep. To Dr. Mather, this didn't look like random action.

An octopus is very different from a mammal. It lives only about two years. It has much less opportunity to gain and use knowledge than an elephant, which has a 50-year lifespan and three generations of a family to learn from. The young octopus learns on its own with minimal contact with other octopuses and no influences of parental care or sibling rivalry. This may be because the octopus has a large brain with vertical and sub-frontal lobes dedicated to storing learned information: it has the anatomy for a robust, built-in intelligence.

But it is not enough to know that anatomy predicts an animal to be intelligent without some idea of how it uses this ability. Investigations at Naples in the 1950s and 1960s found that octopuses can learn a wide array of visual patterns, encoding information mostly by comparing edges, orientations, and shapes. They also learn by touch, and that tactile information is stored in a different area of the brain. Intent on just demonstrating learning abilities at first, researchers did not follow up to find what octopuses were doing with this learning in their ocean home. As concerns about direct experimentation in laboratories on intelligent animals began to emphasize observation of natural behavior in the field, the Naples studies ended, and no link was made between abstract information storage and the use of learning in daily life. In 1996, the works of Roger Hanlon and John Messenger provided an overview of cephalopod behavior in their natural habitat, studying areas such as prey manipulation, personality, and even play in the octopus.

What were octopuses doing with the information that learning studies said they could acquire? One study Mather and Roland C. Anderson undertook in 1999 centered on the "Packaging Problem." The problem posed was how an octopus could get at the soft, delectable clam enclosed in its hard shell. Many predators have evolved means of penetrating the clam's hard shell—sea stars pull the valves apart, seabirds pry them apart, snails drill a hole into the shell, and gulls drop the clam from a carefully calculated height onto rocks or road pavement.

But the octopus does even better than these predators in that it can use an arsenal of different solutions for use in feeding. It has the holding ability of hundreds of suckers and the pulling power of eight muscular arms, flexible because they are boneless. Underneath, inside the mouth at the junction of the arms, it has a parrot-like twin beak for biting. Inside are also two more useful structures, the radula with teeth for rasping and the extendible salivary papilla that delivers cephalotoxin, a neuromuscular function-blocker that can kill a crab in several minutes. Fortunately for Mather and Anderson, only the venom of blue-ringed octopuses has proven fatal to humans.

Since octopuses are well set up to recover and use information for solving the problem of the clam's protection, Mather and Anderson set out to determine what the giant Pacific octopus would do to get at three types of bivalves. Prey species were each opened differently. The fragile mussel shells were simply broken, and the stronger Venus clams were pulled apart. Thick-shelled Protothaca clams were drilled with the octopuses' radula and salivary papilla, or chipped with the beak, then injected with venom, which weakened the muscle holding the valves together. When they were offered the clams opened on the half shell, the octopuses changed preference and consumed both clam species, but hardly any mussels. When they didn't have to work hard for the clam meat, they liked Protothaca. Octopuses could also shift their penetration strategies. When live Venus clams were wired shut with stainless steel wire, the octopuses couldn't pull the valves apart, so they then tried drilling and chipping. Given empty-weighted shells glued shut, the octopuses ignored them; they were on to that trick right away.

Perhaps this individual sensitivity to change, honed by intelligence and variability, has been the key to solving the puzzle of the success of both the cephalopods and the higher vertebrates. Similarities that could lead us to understand the evolution of intelligence in octopuses and humans are few but thought-provoking. Neither group has the protection of a hard exoskeleton. Both have evolved in complex environments; the octopuses in the tropical coral reef and the hominid in the savanna edge. Both have considerable variability among individuals and the ability to change their behavior to help them survive. So, perhaps looking at octopuses through their intelligence, as witnessed by their feeding flexibility, helps us also look at aspects of ourselves as we continue to unpack the evolution of intelligence.

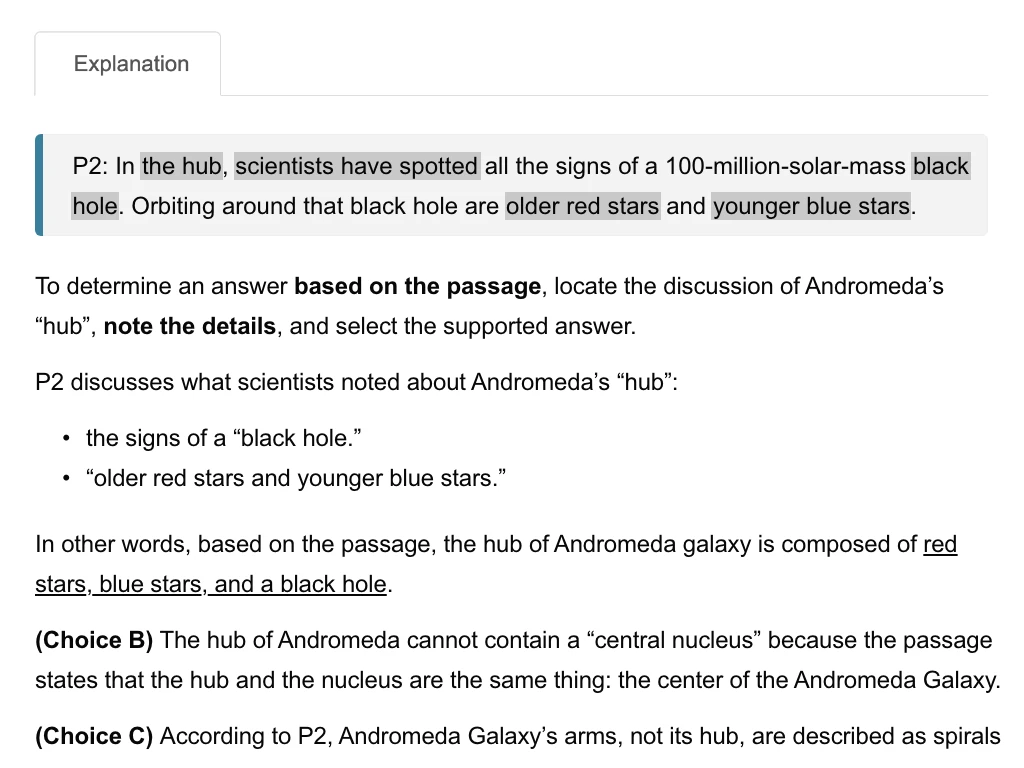

Question

Based on the passage, the notion that octopus behavior is not random is best described as a:

| A. fact that is supported by studies on human intelligence. | |

| B. reasoned judgment from an expert in animal behavior. | |

| C. reasoned judgment from scientists who study anatomy. | |

| D. belief that the passage author proved incorrect. |

Explanation

P1: While watching an octopus in Bermuda, animal behaviorist Jennifer Mather observed it sitting in its sheltering den after a foraging expedition, where it caught several crabs, took them home, and ate them. Suddenly it jetted out directly to a small rock about six feet away, tucked it under its spread arms and jetted back. Going out three times more in different directions, it took up three more rocks and piled the resulting barrier in front of the entrance to its den and went to sleep. To Dr. Mather, this didn't look like random action.

Summarize the discussion connected to the notion (belief) that octopus behavior is not random (occurring without thought or intention) and select the answer that best matches the details of that discussion.

P1 discusses octopus behavior, stating that while studying an octopus, animal behaviorist Jennifer Mather observed behaviors that "didn't look like random action." An animal behaviorist has a high degree of knowledge about animal behavior.

Based on these details, the notion that octopus behavior is not random is best described as a reasoned judgment from an expert in animal behavior.

(Choice A) The final paragraph suggests that studying octopus intelligence might help scientists learn more about human intelligence, but there is no evidence that studies on human intelligence have been used to support ideas about octopus behavior.

(Choice C) Although the passage author implies that an octopus's "anatomy predicts" it to be intelligent, the author also indicates this is not enough to conclude anything about its behavior. Furthermore, the passage doesn't mention any specific scientists who study anatomy.

(Choice D) The passage author notes that the octopus's behavior "didn't look like random action" and offers no evidence to disprove this idea.

Things to remember:

Identify the answer that is based on the passage by reading all the passage evidence about the question's subject.

Passage

INFORMATIONAL: This passage is adapted from the article "Octopuses are Smart Suckers!?" by Jennifer Mather (© 2000 by Jennifer Mather).

While watching an octopus in Bermuda, animal behaviorist Jennifer Mather observed it sitting in its sheltering den after a foraging expedition, where it caught several crabs, took them home, and ate them. Suddenly it jetted out directly to a small rock about six feet away, tucked it under its spread arms and jetted back. Going out three times more in different directions, it took up three more rocks and piled the resulting barrier in front of the entrance to its den and went to sleep. To Dr. Mather, this didn't look like random action.

An octopus is very different from a mammal. It lives only about two years. It has much less opportunity to gain and use knowledge than an elephant, which has a 50-year lifespan and three generations of a family to learn from. The young octopus learns on its own with minimal contact with other octopuses and no influences of parental care or sibling rivalry. This may be because the octopus has a large brain with vertical and sub-frontal lobes dedicated to storing learned information: it has the anatomy for a robust, built-in intelligence.

But it is not enough to know that anatomy predicts an animal to be intelligent without some idea of how it uses this ability. Investigations at Naples in the 1950s and 1960s found that octopuses can learn a wide array of visual patterns, encoding information mostly by comparing edges, orientations, and shapes. They also learn by touch, and that tactile information is stored in a different area of the brain. Intent on just demonstrating learning abilities at first, researchers did not follow up to find what octopuses were doing with this learning in their ocean home. As concerns about direct experimentation in laboratories on intelligent animals began to emphasize observation of natural behavior in the field, the Naples studies ended, and no link was made between abstract information storage and the use of learning in daily life. In 1996, the works of Roger Hanlon and John Messenger provided an overview of cephalopod behavior in their natural habitat, studying areas such as prey manipulation, personality, and even play in the octopus.

What were octopuses doing with the information that learning studies said they could acquire? One study Mather and Roland C. Anderson undertook in 1999 centered on the "Packaging Problem." The problem posed was how an octopus could get at the soft, delectable clam enclosed in its hard shell. Many predators have evolved means of penetrating the clam's hard shell—sea stars pull the valves apart, seabirds pry them apart, snails drill a hole into the shell, and gulls drop the clam from a carefully calculated height onto rocks or road pavement.

But the octopus does even better than these predators in that it can use an arsenal of different solutions for use in feeding. It has the holding ability of hundreds of suckers and the pulling power of eight muscular arms, flexible because they are boneless. Underneath, inside the mouth at the junction of the arms, it has a parrot-like twin beak for biting. Inside are also two more useful structures, the radula with teeth for rasping and the extendible salivary papilla that delivers cephalotoxin, a neuromuscular function-blocker that can kill a crab in several minutes. Fortunately for Mather and Anderson, only the venom of blue-ringed octopuses has proven fatal to humans.

Since octopuses are well set up to recover and use information for solving the problem of the clam's protection, Mather and Anderson set out to determine what the giant Pacific octopus would do to get at three types of bivalves. Prey species were each opened differently. The fragile mussel shells were simply broken, and the stronger Venus clams were pulled apart. Thick-shelled Protothaca clams were drilled with the octopuses' radula and salivary papilla, or chipped with the beak, then injected with venom, which weakened the muscle holding the valves together. When they were offered the clams opened on the half shell, the octopuses changed preference and consumed both clam species, but hardly any mussels. When they didn't have to work hard for the clam meat, they liked Protothaca. Octopuses could also shift their penetration strategies. When live Venus clams were wired shut with stainless steel wire, the octopuses couldn't pull the valves apart, so they then tried drilling and chipping. Given empty-weighted shells glued shut, the octopuses ignored them; they were on to that trick right away.

Perhaps this individual sensitivity to change, honed by intelligence and variability, has been the key to solving the puzzle of the success of both the cephalopods and the higher vertebrates. Similarities that could lead us to understand the evolution of intelligence in octopuses and humans are few but thought-provoking. Neither group has the protection of a hard exoskeleton. Both have evolved in complex environments; the octopuses in the tropical coral reef and the hominid in the savanna edge. Both have considerable variability among individuals and the ability to change their behavior to help them survive. So, perhaps looking at octopuses through their intelligence, as witnessed by their feeding flexibility, helps us also look at aspects of ourselves as we continue to unpack the evolution of intelligence.

Question

It can reasonably be inferred from the passage that octopus intelligence is of particular interest because scientists don't yet fully understand:

| A. how intelligence helps octopuses communicate. | |

| B. how intelligence is used by octopuses in their natural environment. | |

| C. why intelligence is displayed only by some octopuses. | |

| D. why intelligence in octopuses is so difficult to study. |

Explanation

P3: But it is not enough to know that anatomy predicts an animal to be intelligent without some idea of how it uses this ability. Investigations at Naples in the 1950s and 1960s found that octopuses can learn a wide array of visual patterns…. Intent on just demonstrating learning abilities at first, researchers did not follow up to find what octopuses were doing with this learning in their ocean home…and no link was made between abstract information storage and the use of learning in daily life.

P4: What were octopuses doing with the information that learning studies said they could acquire? One study Mather and Roland C. Anderson undertook in 1999 centered on the "Packaging Problem." The problem posed was how an octopus could get at the soft, delectable clam enclosed in its hard shell.

To infer an answer, summarize the details related to what scientists are trying to learn about octopus intelligence and pick the answer that can be concluded from those details.

Several paragraphs mention what scientists don't yet understand about octopus intelligence:

| P3 | Research in the 1950s and 1960s explored octopuses' intelligence and learning abilities, but this research did not find how octopuses used their learning "in their ocean home" and "in daily life." |

| P4 | Scientists hoped to determine what octopuses do with the information they acquire. One study examined how octopuses opened different kinds of bivalve prey, like clams. |

These details indicate that octopuses haven't been sufficiently studied in their natural habitat to show all the ways in which they use their intelligence.

Thus, it can be reasonably inferred that scientists don't yet fully understand how intelligence is used by octopuses in their natural environment.

(Choices A and D) The passage provides no evidence to suggest that scientists are studying how intelligence helps octopuses communicate or that octopus intelligence is difficult to study.

(Choice C) The passage never suggests that some octopuses display intelligence while others do not. P2 describes all octopuses as having a "large brain" and a "robust, built-in intelligence."

Things to remember:

Answer an inference question by summarizing the passage's details about the topic and drawing a logical conclusion.

Passage A by Kate Flint

All photography requires light, but the light used in flash photography is unique—shocking, intrusive, and abrupt. Unlike the light that comes from the sun, or even from ambient illumination, flash explodes suddenly into the darkness.

In the early days of flash photography, a sense of quasi-divine revelation was invoked by some flash photographers, especially when documenting deplorable social conditions. The filthy darkness in which the urban poor lived could not have been photographed otherwise. Jacob Riis, working in New York in the late 1880s, used spiritual language to underscore flash's significance as an instrument to expose—and hopefully rectify—the horrid conditions of those living in urban squalor.

It's in relation to documentary photography that we most starkly encounter flash's contradictory aspects. It makes visible that which would otherwise remain in darkness; to do so requires an intrusion, a rupturing of private lives and interiors. Yet flash brings a form of democracy to the material world. Formerly insignificant details take on unplanned prominence, as we see in the work of those Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers who used flash in the 1930s and laid bare the reality of poverty during the Depression. A sudden flare of light reveals each dent on a kitchen utensil and the label on each carefully stored can; each cherished ornament on the mantle; each wrinkle of the skin.

These FSA photographers used flash bulbs, not powder. Pioneered in the late 1920s, these bulbs became generally available around 1930, their ease and portability transforming the abilities of press photographers, documentarians, even police photographers, who could now record evidence of crimes committed under the cover of darkness. But the history of flash photography is about speed as well as light. The breathtaking, high-speed images produced by Harold Edgerton in the mid-20th century, enabled by very high-speed bursts of light from electrically-controlled neon tubes, created the illusion of stopped motion: bullets piercing playing cards or balloons; golfers and tennis players swinging at balls. The ordinary became strange and beautiful through stroboscopic flash.

These examples challenge the bad press that flash photography has received over the century and a half since its invention. Sudden and surprising light continues to be imaginatively deployed by inventive photographers, once again making luminous something of the original wonder that attended flash.

Passage B by Kate Flint

Susan Sontag was deliberately provocative when she coupled photography with violence. There is, she wrote in 1977, "something predatory in the act of taking a picture." She pointed out that we speak casually about "loading" and "aiming" a camera: "Just as the camera is a sublimation of a gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated violation of privacy." Sontag's hyperbole prodded her readers to consider the identity-freezing that is implicit in each portrait that is shot.

But it is less of an exaggeration to couple violence with one particular photographic technology: flash. From the earliest decades of flash photography, when limelight or magnesium was used to illuminate darkness, flash was associated with explosive unpredictability. Even after flash powder was invented in 1887, accidents were commonplace, maiming and injuring photographers. Not until flash bulbs were introduced around 1930 did the means for producing sudden blasts of artificial light become easier and more dependable, and this increased with the advent of the Speedlite and other electronic flash guns.

"Flash gun"—that nomenclature takes us full circle, since some of the early contraptions for igniting flash powder indeed looked much like a revolver. The name, and the linkage to violence and weaponry, stuck. The allusion is clear in the black humor of the words that decorated some military gun barrels in World War II: "Smile. Wait for flash." Weaponry and photography work in consort in Alfred Hitchcock's film Foreign Correspondent, in which a man posing as a news photographer fires a weapon at the same moment that he sets off his camera flash.

Flash can also enact a form of ethical violence. Among those who worked for the Farm Security Administration during the Depression, Dorothea Lange saw its use as invasive, and Ben Shahn expressed his doubts--both about photographing someone else's private space and about flash's aesthetics. "When some of the people came in and began to use flash I thought it was immoral," he said. "You know, you come into a sharecropper's cabin and it's dark. But a flash destroyed that darkness." Another photographic artist, Henri Cartier-Bresson, also shunned the flash, in part due to its association with newsmen and detective work. No one more famously brought flash and crime together than the man known as Weegee, working in mid-20th-century New York to record criminal activity. "A photographer is a hunter with a camera," he said, anticipating Sontag.

Nowhere has this determined violation and exploitation been more apparent than in the work of paparazzi. Popping flash bulbs have become visual shorthand for the achievement of notoriety, as well as the price paid for that fame. Think of King Kong—captured, brought to New York City, exhibited on stage, and then startled into destructive rage by newspaper photographers. Whether viewed as exposure or exploitation, flash photography is historically, and disconcertingly, inseparable from violence.

Question

This question asks about Passage A

One reasonable inference from Passage A is that before the mid-20th century, photographers had not yet figured out:

| A. ways to replace flash powder with portable flash bulbs. | |

| B. how they would use their photos to document the lives of the poor. | |

| C. whether people would object to the intrusion of flash photography. | |

| D. ways to create photographic images of movements too fast for the human eye to see. |

Explanation

P4: But the history of flash photography is about speed as well as light. The breathtaking, high-speed images produced by Harold Edgerton in the mid-20th century, enabled by very high-speed bursts of light from electrically-controlled neon tubes, created the illusion of stopped motion: bullets piercing playing cards or balloons; golfers and tennis players swinging at balls.

When a question asks what can be reasonably inferred from a passage, the answer will be a conclusion that you draw from the text.

The question requires you to examine any references to the mid-20th century (around the 1950s) and infer (draw a conclusion) what flash photographers had not discovered until then. Skim the answer choices and eliminate any that are not supported by the text. The correct answer will be something that happened in the mid-20th century or later.

| (Choice A) ways to replace flash powder with portable flash bulbs | P4 notes that "FSA photographers used flash bulbs, not powder…in the late 1920s," which was before the mid-20th century. |

| (Choice B) how they would use their photos to document the lives of the poor | P2 mentions Jacob Riis documenting the lives of the poor in the 1880s. This was well before the mid-20th century. |

| (Choice C) whether people would object to the intrusion of flash photography | Passage A doesn't discuss whether people objected to flash photography. |

| (Choice D) ways to create photographic images of movements too fast for the human eye to see | P4 states that "the…images produced…in the mid-20th century…created the illusion of stopped motion [which the eye cannot see in real time]," implying that photographers had not figured out how to create images of movements too fast for the human eye to see before this time. |

Things to remember:

When asked what can be inferred from the passage, summarize the details and determine which answer choice is logically supported by those details.

Passage

INFORMATIONAL: This passage is adapted from the article "Octopuses are Smart Suckers!?" by Jennifer Mather (© 2000 by Jennifer Mather).

While watching an octopus in Bermuda, animal behaviorist Jennifer Mather observed it sitting in its sheltering den after a foraging expedition, where it caught several crabs, took them home, and ate them. Suddenly it jetted out directly to a small rock about six feet away, tucked it under its spread arms and jetted back. Going out three times more in different directions, it took up three more rocks and piled the resulting barrier in front of the entrance to its den and went to sleep. To Dr. Mather, this didn't look like random action.

An octopus is very different from a mammal. It lives only about two years. It has much less opportunity to gain and use knowledge than an elephant, which has a 50-year lifespan and three generations of a family to learn from. The young octopus learns on its own with minimal contact with other octopuses and no influences of parental care or sibling rivalry. This may be because the octopus has a large brain with vertical and sub-frontal lobes dedicated to storing learned information: it has the anatomy for a robust, built-in intelligence.

But it is not enough to know that anatomy predicts an animal to be intelligent without some idea of how it uses this ability. Investigations at Naples in the 1950s and 1960s found that octopuses can learn a wide array of visual patterns, encoding information mostly by comparing edges, orientations, and shapes. They also learn by touch, and that tactile information is stored in a different area of the brain. Intent on just demonstrating learning abilities at first, researchers did not follow up to find what octopuses were doing with this learning in their ocean home. As concerns about direct experimentation in laboratories on intelligent animals began to emphasize observation of natural behavior in the field, the Naples studies ended, and no link was made between abstract information storage and the use of learning in daily life. In 1996, the works of Roger Hanlon and John Messenger provided an overview of cephalopod behavior in their natural habitat, studying areas such as prey manipulation, personality, and even play in the octopus.

What were octopuses doing with the information that learning studies said they could acquire? One study Mather and Roland C. Anderson undertook in 1999 centered on the "Packaging Problem." The problem posed was how an octopus could get at the soft, delectable clam enclosed in its hard shell. Many predators have evolved means of penetrating the clam's hard shell—sea stars pull the valves apart, seabirds pry them apart, snails drill a hole into the shell, and gulls drop the clam from a carefully calculated height onto rocks or road pavement.

But the octopus does even better than these predators in that it can use an arsenal of different solutions for use in feeding. It has the holding ability of hundreds of suckers and the pulling power of eight muscular arms, flexible because they are boneless. Underneath, inside the mouth at the junction of the arms, it has a parrot-like twin beak for biting. Inside are also two more useful structures, the radula with teeth for rasping and the extendible salivary papilla that delivers cephalotoxin, a neuromuscular function-blocker that can kill a crab in several minutes. Fortunately for Mather and Anderson, only the venom of blue-ringed octopuses has proven fatal to humans.

Since octopuses are well set up to recover and use information for solving the problem of the clam's protection, Mather and Anderson set out to determine what the giant Pacific octopus would do to get at three types of bivalves. Prey species were each opened differently. The fragile mussel shells were simply broken, and the stronger Venus clams were pulled apart. Thick-shelled Protothaca clams were drilled with the octopuses' radula and salivary papilla, or chipped with the beak, then injected with venom, which weakened the muscle holding the valves together. When they were offered the clams opened on the half shell, the octopuses changed preference and consumed both clam species, but hardly any mussels. When they didn't have to work hard for the clam meat, they liked Protothaca. Octopuses could also shift their penetration strategies. When live Venus clams were wired shut with stainless steel wire, the octopuses couldn't pull the valves apart, so they then tried drilling and chipping. Given empty-weighted shells glued shut, the octopuses ignored them; they were on to that trick right away.

Perhaps this individual sensitivity to change, honed by intelligence and variability, has been the key to solving the puzzle of the success of both the cephalopods and the higher vertebrates. Similarities that could lead us to understand the evolution of intelligence in octopuses and humans are few but thought-provoking. Neither group has the protection of a hard exoskeleton. Both have evolved in complex environments; the octopuses in the tropical coral reef and the hominid in the savanna edge. Both have considerable variability among individuals and the ability to change their behavior to help them survive. So, perhaps looking at octopuses through their intelligence, as witnessed by their feeding flexibility, helps us also look at aspects of ourselves as we continue to unpack the evolution of intelligence.

Question

The main purpose of the last paragraph is to:

| A. suggest that octopuses' adaptability may offer insights into the evolution of human intelligence. | |

| B. explain the primary function of exoskeletons. | |

| C. explore the differences between humans' and octopuses' feeding habits. | |

| D. describe the way humans learn by observing the variability of octopuses. |

Explanation

P7: Perhaps this individual sensitivity to change, honed by intelligence and variability, has been the key to solving the puzzle of the success of both the cephalopods and the higher vertebrates. Similarities that could lead us to understand the evolution of intelligence in octopuses and humans are few but thought-provoking. Neither group has the protection of a hard exoskeleton. Both have evolved in complex environments…. Both have considerable variability among individuals and the ability to change their behavior to help them survive. So, perhaps looking at octopuses through their intelligence, as witnessed by their feeding flexibility, helps us also look at aspects of ourselves as we continue to unpack the evolution of intelligence.

To determine the purpose of a paragraph, highlight any repeated ideas that help the author reinforce the point.

The last paragraph (P7) draws a parallel between the evolution and adaptability of octopuses and humans. The paragraph discusses octopuses' and humans' "sensitivity to change" and their "ability to change their behavior" to survive, suggesting this adaptability may hold the "key" to explaining the success of "cephalopods" (octopuses) and "higher vertebrates" (including humans).

The final sentence states that looking at octopuses' intelligence, particularly their "feeding flexibility," or ability to adapt their strategy to access food, may help us understand human intelligence.

The descriptions of adaptability and the final statement indicate that the paragraph's main purpose is to suggest that octopuses' adaptability may offer insights into the evolution of human intelligence.

(Choice B) The paragraph briefly mentions that octopuses and humans lack exoskeletons, but this is not the paragraph's main or repeated idea.

(Choice C) The last paragraph mentions the feeding habits of octopuses, but not of humans.

(Choice D) The paragraph suggests that humans might learn something about their own intelligence by observing the variability of octopuses, which explains WHAT humans might learn, but the paragraph does not describe the WAY humans learn.

Things to remember:

The main purpose of a paragraph will be a broad idea presented throughout the entire paragraph.

Benefits of Practicing ACT Reading Exam-Like Samples

Unlimited Exam-level Practice

Customized to Your Needs

Understand the Why

Score Free ACT Questions Every Week!

Get ACT exam-ready with weekly exam-like questions sent to your inbox.

Get a 36 on ACT Reading Section with UWorld

“UWorld's question bank can be described in one word: revolutionary. It accurately models the content that you would see on the test and familiarizes you with the test through PRACTICE, not mindless reading of the content. After using UWorld's amazing question bank, I was able to score a 36. It's proven to work and yielded amazingly good results for me!”

- Ravi

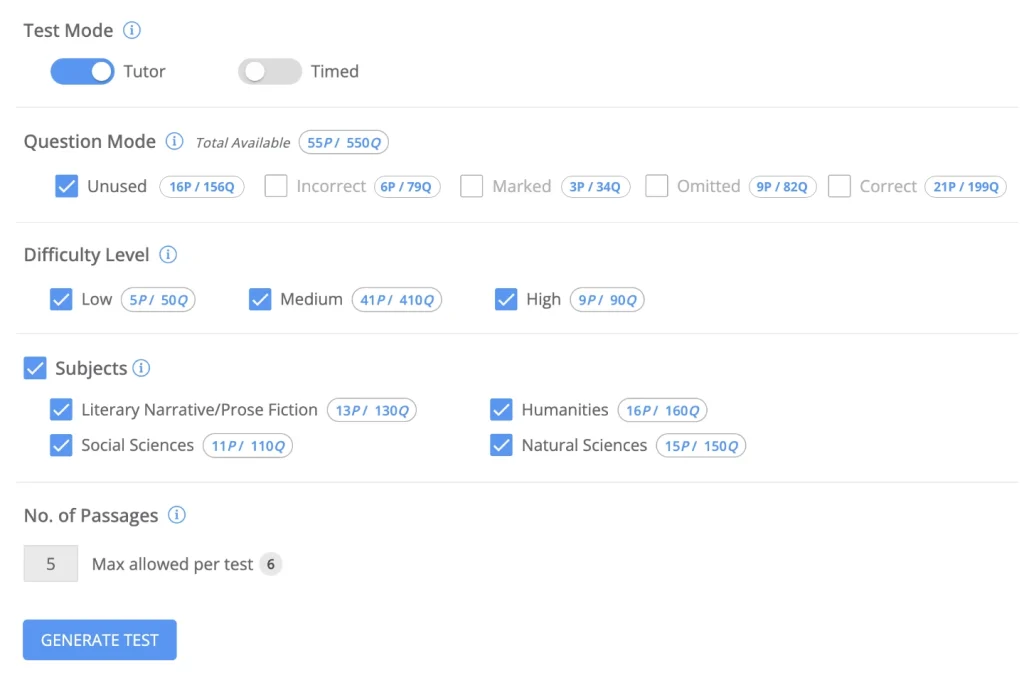

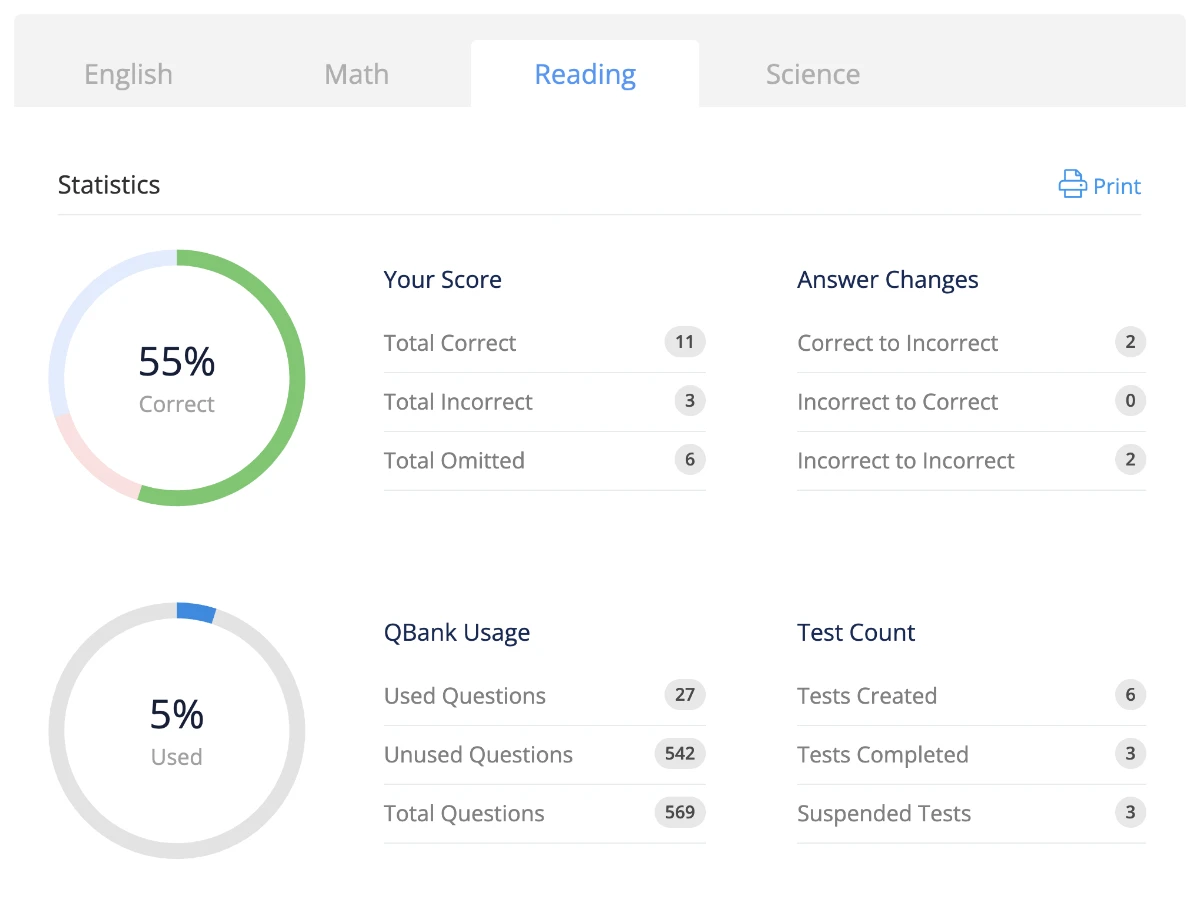

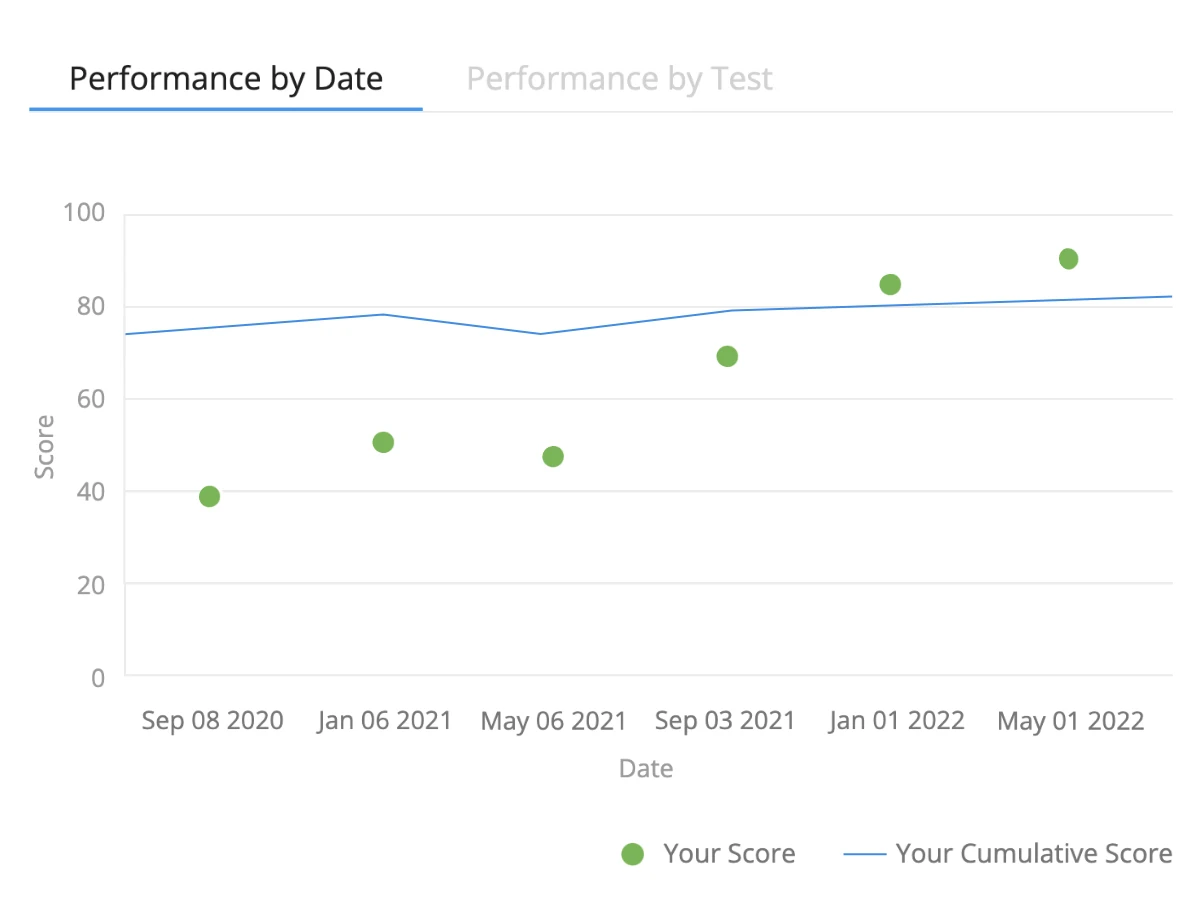

Create Unlimited Practice Tests with Exam-Level Questions

- Generate unlimited ACT sample Reading tests from hundreds of exam-level questions.

- Target your weaknesses by customizing a test based on topic, custom tag, or even just questions you’ve previously gotten wrong.

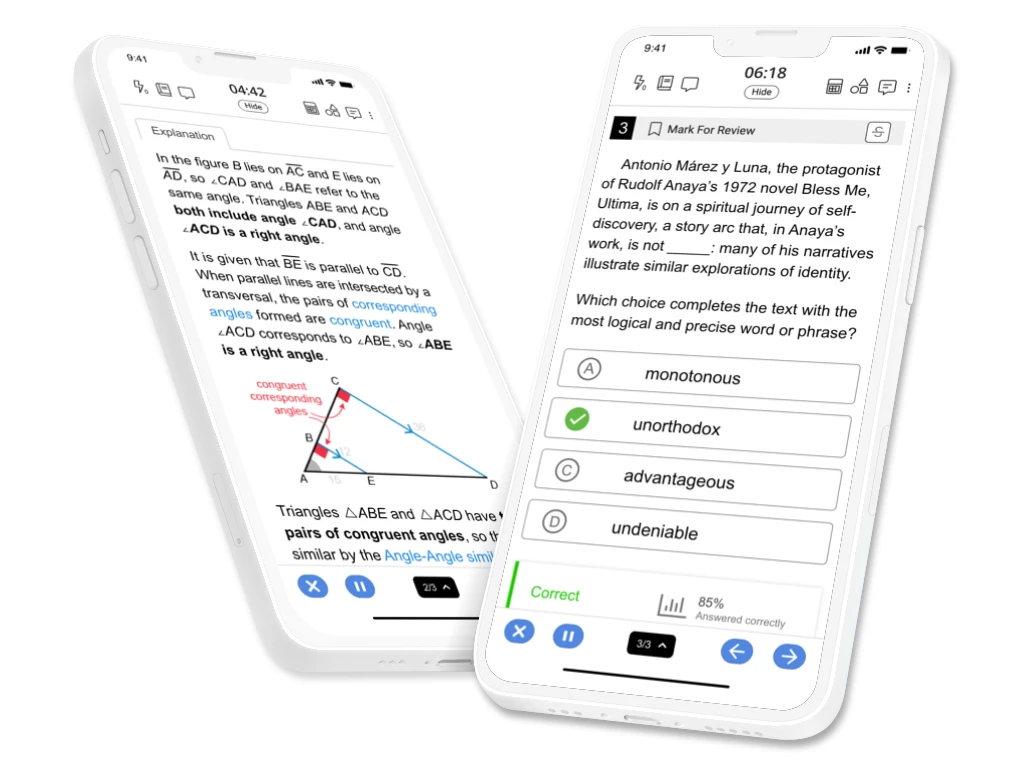

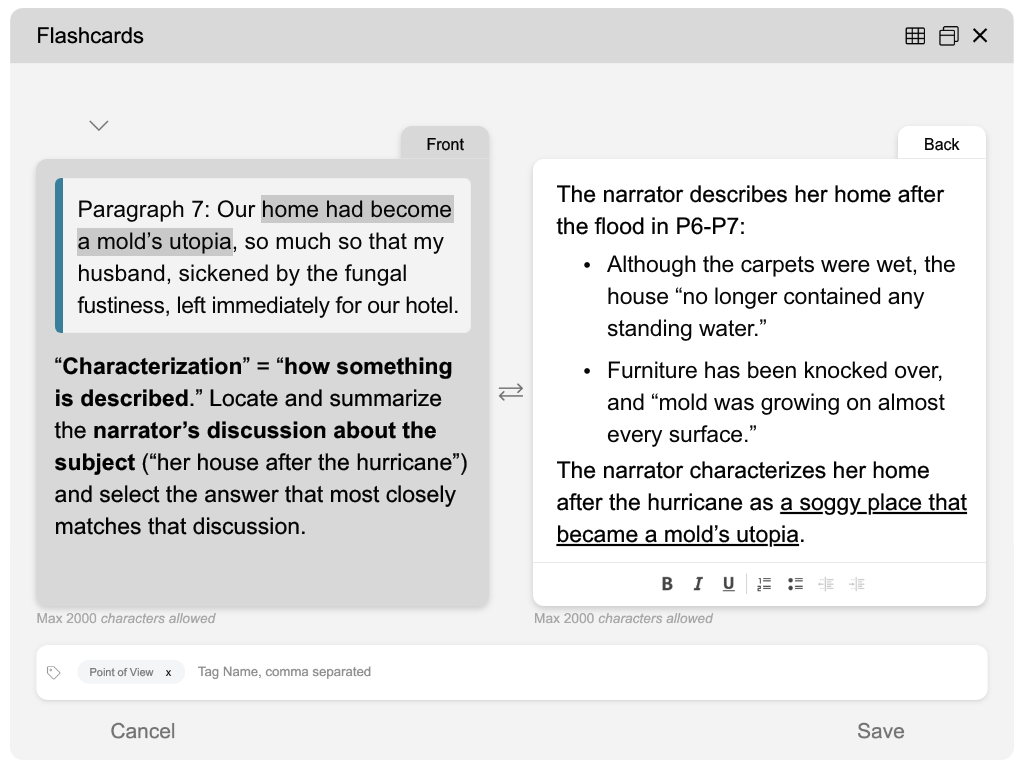

Understand Every Answer Choice

- It's not enough to know the right answer. You must understand why it's right or wrong.

- That’s why every UWorld ACT Reading sample question includes detailed explanations and professional illustrations to help concepts click instantly.

Features: My Notebook & Flashcards

- Discover a helpful explanation or a visual representation of a formula? Simply click, highlight, and select to create notes or flashcards effortlessly.

- Transfer QBank visual and written content to your My Notebook or digital flashcards organized by topic or custom tag.

- Our mobile app ensures it's always within arm's reach.

Get Exam-Ready with Realistic Practice!

If your practice feels like the real ACT, then the real exam will feel like practice. UWorld’s ACT Reading sample tests simulate the actual testing experience, so there are no surprises on exam day—only confidence.

Practice ACT Reading Sample Questions Anywhere at Any Time

Excellent Exam Results Make Happy Students

I got a 35 from studying using UWorld, it has the best question bank along with the most informative explanations.”

UWorld contributed to a 10 point increase for me on the ACT. The website was FANTASTIC for me to practice on the go. I especially liked the math section.”

The primary reason for me being extremely likely to recommend UWorld to a friend is because it has helped me prepare and achieve a 35 Composite ACT Score!